Vermont is already warmer and wetter because of climate change, a new report affirms, and researchers expect the state’s ecosystems, industries and communities to change dramatically in the coming decades.

Throughout the past year, Vermont has experienced a range of impacts that are likely connected to climate change, such as drought conditions and flooding in southern Vermont.

Blue-green algae bloomed in Lake Champlain, mosquitoes swarmed in Addison County and Mount Mansfield, the state’s tallest peak, set its record for the latest freeze — more than a week later than its previous record.

Changes like these are likely to continue and accelerate, according to the 2021 Vermont Climate Assessment.

At a press conference Tuesday, researchers and advisers from the University of Vermont and the Nature Conservancy presented the study, which built on the 2014 Climate Assessment, the first state-level climate study in the country. Gillian Galford, research associate professor with UVM’s Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources, and Joshua Faulkner, research assistant professor with University of Vermont Extension, led the assessment.

Lesley-Ann Dupigny-Giroux, Vermont’s state climatologist who recently spoke via remote video at the UN climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland, also served as an adviser of the study.

“Climate change is here,” said Stephen Posner, policy director at UVM’s Gund Institute for Environment and an adviser of the assessment. “It’s impacting communities across Vermont now, today. We can see that happening when we look at the data and the scientific evidence.”

Though the climate likely will remain relatively mild in Vermont — possibly prompting climate migration in the coming decades — average temperatures have already risen by 2 degrees Fahrenheit, and may warm by between 5 and 9 degrees more by 2100, depending on the emissions scenario, according to the study.

Vulnerable groups face an even bigger risk than the average population, a fact state and local officials should account for in their planning efforts, the assessment said.

Many iconic Vermont features are at risk. In 25 years, the common loon and the hermit thrush could disappear from the state, along with dozens of other bird species, the study said. Projected fluctuations in temperature mean ski resorts likely will need to rely on robust snowmaking operations to keep the industry viable until 2050, and maple sugarers could face a decrease in production.

“The goal here, really, is to help inform many different types of decision-makers here in Vermont, from lawmakers to farmers,” Posner said. “This report is written to help citizens and decision-makers make sense of climate data and prepare for future impacts across these kinds of sectors.”

Temperature

Climate change has caused average Vermont temperatures to rise by 2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1990, according to the assessment.

Since 1900, the freeze-free period — the number of consecutive days with minimum temperatures above 28 degrees Fahrenheit — “increased at a rate of 1.7 days per decade, which accelerated to 4.4 days per decade since 1960 and again to 9.0 days per decade since 1991,” it said.

Temperature changes have affected the winter season most dramatically and rapidly, according to the assessment. Since 1960, winter temperatures have risen 2.5 times faster than average annual temperatures, and water bodies are thawing sooner each spring.

Southeastern Vermont experienced the most significant warming trend in winter, followed by northeastern and western Vermont, according to the assessment. The average number of “very cold nights” has decreased across the state.

“Climate change is already progressing more rapidly in southern Vermont,” Galford, an author of the assessment, said Tuesday. “We may see different effects in different parts of the state.”

Water

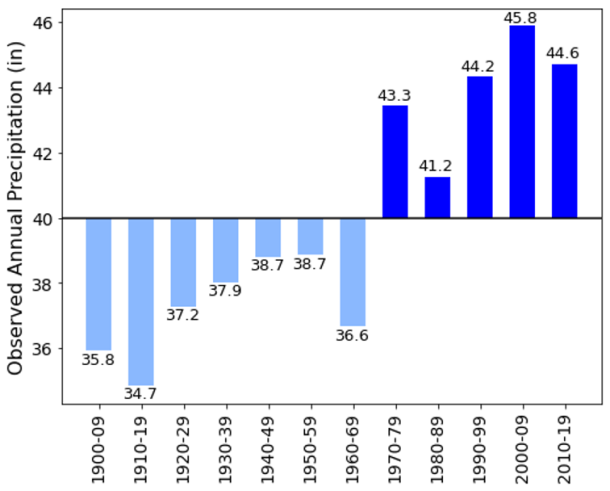

Between the early 1900s and 2020, average yearly precipitation increased by 21%, marking an increase of 1.4 inches per decade, the study said. In the early 1900s, Vermont’s annual precipitation was akin to average precipitation amounts in Chicago. Now, precipitation in Vermont looks more like an average year for Portland, Oregon.

Researchers expect flooding to increase, which means improved stormwater infrastructure could reduce damage to homes, roads, bridges and farm fields. Increased rain likely would cause more runoff from farms and developed surfaces into streams, lakes and ponds. Runoff and warmer water temperatures could create ideal conditions for blue-green algae blooms.

Still, amounts of rain and snow remain “highly variable from year to year” — droughts and prolonged dry spells are projected to become more frequent, too.

“I have absolutely seen farmers dealing with more drought, and that’s evidenced by really a strong uptick in interest in irrigation-related information and understanding what technologies are available to implement on their farms,” Faulkner, an author of the study, said Tuesday.

That variability means that, “while Vermont’s winters may become milder and less snowy on average, any given year could be quite snowy,” the study said.

Plants and animals

Changes in temperature and precipitation would likely prompt a web of other troubling impacts on Vermont’s nonhuman life, according to the assessment.

For example, migratory birds “rely on booms in insect populations during the spring to recover from the physical strains of traveling and to support reproductive strategies,” it said.

If the birds migrating through the state miss that insect boom because of changes in temperature or water, they might be “unable to take full advantage of the insect boom and may starve or fail to reproduce,” the study said.

Temperature changes that affect habitat could harm species like the Bicknell’s thrush, which relies on alpine vegetation to breed.

The common loon and hermit thrush are among 92 bird species expected to disappear from Vermont in the next 25 years, according to the assessment. Over time, moose populations likely will decline, while white tailed deer populations are projected to grow. As conditions become more ideal for bugs such as mosquitoes and ticks, insect-related diseases also may become more prevalent.

Forests are beginning to see effects from climate change, according to the study. Some tree species that tolerate warmer temperatures — northern red oak, shagbark hickory and black cherry, for example — may benefit in the future. Others, such as sugar maple, balsam fir, yellow birch and black ash will be negatively impacted, according to the assessment.

“While growing conditions will be significantly different by 2100, actual change in forest makeup will follow a delay as older trees die and are replaced by young ones,” it said.

Forests may also face threats from growing populations of pests, invasive plants and diseases.

Bringing it home

Vermont’s Climate Council is racing to meet a Dec. 1 deadline for its Climate Action Plan, which would guide stakeholders throughout the state as they attempt to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prepare the state for climate change. Several of the assessment’s advisers serve on the climate council, and Posner said Tuesday the assessment has been shared with council members.

The temperature projections included in the assessment, however, are based on global greenhouse gas emissions. Leaders from around the world are negotiating climate policies that could lower emissions at the COP26 conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

The study is intended to make broad information about climate relevant to Vermonters, Galford said Tuesday.

“I know that when we receive information on the national scale or about New England, it’s very hard to enact decisions, policies, plans at a really local scale — at the scale of our town, and the scale of our farm, at the scale of our state,” she said. “I hope that this information is empowering in making those decisions on those more local scales.”