A century ago, Vermont faced its greatest political scandal.

Today it is all but forgotten.

This is the last of a three-part series on the rise and fall of Gov. Horace Graham, by Ben Heintz, who teaches social studies and journalism at U-32 High School in East Montpelier. Part 1 can be read here; Part 2 is here.

[S]electing a jury was near impossible. A number of the older men were excused for deafness, and one, C.A. Ainsworth of Cabot, did not appear when drawn, having been dead more than a year.

It had also been 14 months since Horace Graham’s indictment, and many in the pool were excused for having “formed and expressed an opinion” on the question of their former governor’s guilt.

A few men, however, “had read very little,” like the logger Carl Richardson of Worcester, who could not swear to his age, or R.J. Batchelder, a farmer from Plainfield, who said he had heard the case discussed, “but had not entered into the arguments.”

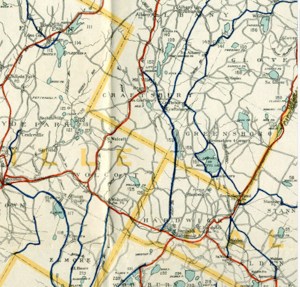

In the end, despite the efforts of his influential friends, Horace Graham’s fate would be decided by 12 common men of Washington County:

H.E. Badger, 72, farmer, Middlesex.

Samuel Baird, 69, farmer, Waterbury.

R.J. Batchelder, 61, farmer, Plainfield.

Frank Barney, 59, blacksmith, Berlin.

R.E. Campbell, 23, farmer, Fayston.

Fred Cram, 68, farmer, Roxbury.

Don C. Turner, 57, railroad clerk, Montpelier.

Jerome Stone, 61, carpenter, Northfield.

Frank W. Smith, 52, farmer, Middlesex.

Carl Richardson, lumberman, Worcester.

E.P. Orcutt, 34, farmer, Roxbury.

T.J. Ferris, 60, undertaker, Moretown.

The lead prosecutor, former Attorney General Herbert G. Barber, described their task as “the most important case ever tried in Vermont,” but as they took their seats in the jury box, there were only six onlookers in the gallery. After a year of delays, Graham’s case had faded from most Vermonters’ minds.

A handful of reporters were also in the room, and because the transcripts of Graham’s trial were lost in the 1927 flood, we rely on their work for our version of events. Thus we know that Horace Graham shook hands with a number of “prominent figures” on his way into the building and up the stairs to the courtroom, that he was “outwardly calm,” that he stood and said “not guilty” in “a clear, firm voice,” and waived the reading of his indictment — 152 counts of larceny and 10 counts of embezzlement — before he returned to his chair.

The case turned on the question of intent. If Graham had simply made errors, there was no larceny. Over the next several days the prosecution called a long line of witnesses, building the case that Graham intended to steal and sought to conceal his crime.

Jesse E. Joslyn, deputy auditor, was asked to examine “file 4501,”one of the auditor’s account books. On the stand, Joslyn “took his position at the distribution ledger and read that he had changed the figures … from $18,199.11 to $22,547.76.” He had made alterations at a later date, under Graham’s orders.

Edward H. Deavitt, the former state treasurer, testified about Graham first months as governor, after the “discrepancies” on his books were discovered by the auditor who replaced him. Deavitt admitted that he had toured around the state on Graham’s behalf, “making requests” of wealthy men in Graham’s circle, collecting money in the effort to pay Graham’s debts to the state.

The prosecution was relentless. There was extensive testimony surrounding the funding for the Greensboro Gulf Road, for which a number of vouchers were missing. A string of bankers demonstrated that Graham had been moving money through accounts in his name all over Vermont.

A picture was forming for the jury — Graham’s actions weren’t those of an innocent man. All that was missing was a motive.

The bankers’ testimony established that in spite of the flow of money into his accounts, Graham could never keep his head above water. He had overdrawn one account in a Newport bank 10 times. It seemed increasingly clear he was motivated to his crimes by debt.

Then came the testimony of Benjamin Gates, who had taken over from Graham as auditor and confronted Graham about the “irregularities” on the books. Gates testified that Graham had told him “he was obliged to take the money to prevent United States Senator Carroll S. Page forcing him into bankruptcy.”

Gates had dropped a big name, under oath. Sen. Page was a former Vermont governor, and an old ally of the Proctors. He made his fortune in leather, but he also had a hand in the lumber business, like Graham, and loaned money from his own banks in his hometown of Hyde Park, the neighboring town to Graham’s Craftsbury.

Was this what J. Rolf Searles was referring to, back when the scandal broke, when he warned Percival Clement about the “past office holders” and “vital interests” that could be exposed if Graham was prosecuted?

Barber drove home the connection when he demonstrated that Graham had deposited a “state’s order” into a Newport bank, then drawn a check from that account to pay a note in a “Hyde Park bank of which Carroll S. Page is president.”

In the face of the mounting evidence, Graham’s lead attorney, his old friend W.B.C. Stickney, was forced to assert an unlikely story. Previous auditors had sometimes moved public money through their personal accounts. Graham thought he had the right to use the state’s money, so long as he paid it back.

This logic was thin, and by the time Graham himself finally took the stand, Stickney was painting the trial as a politically motivated farce. He mocked the absurdity of the charges, and Graham played along, smiling on the stand.

“Did you in drawing any of these orders intend to appropriate and convert the money to your own personal use?”

“No sir, I never did.”

“That is, in short, to steal it from the state?”

“No sir.”

“Are you sure of it?”

Graham laughed out loud. “Yes, I think I am, Mr. Stickney.”

“Have you any doubt of it?”

“Not a particle.”

But a few minutes later, in the same testimony, Stickney’s routine with Graham ran aground. Just as Graham was about to speak, responding to a question about the order of events, Rufus H. Brown and Hale K. Darling, Graham’s other lawyers, interrupted, calling Stickney back to the table for a conference.

After a moment Stickney asked the judge for a word with his client. He approached the witness stand, and whispered something to Graham, who answered “No,” “so emphatically that no one in the courtroom had trouble hearing it.” The lawyer and his client weren’t on the same page.

When the prosecution had their turn with Graham, they pressed their advantage.

“Sometimes the amount which was due the State ran as high as $5,000 a year, didn’t it?”

“I won’t undertake to tell the exact amount.”

“And you used this money in your own personal business?”

“… There were mingled funds. Some belonged to the State and some belonged to me. I checked against this mingled bank account.”

For most of the jurors — farmers, a blacksmith, a lumberman — the arcane accounting details and legal language of the case must have been confounding. But “mingled funds” did not sound good.

The prosecution pushed further.

“Why did you stop at $19,000?”

“I thought I ought not to take any more money than I could account for.”

“If you had the right to take $19,000, would you have the right to take ten times that amount?”

“That might be true,” Graham replied. His certainty had deserted him.

In the prosecution’s closing arguments, Barber reminded the jurors of Graham’s actions during his last month as auditor, when he had “dipped in for $900 more.” The state only asked for justice, Barber said, “the same that would be given a bootblack.”

Rufus E. Brown made the closing arguments in Graham’s defense. The former governor, who led Vermont through the war, didn’t deserve to be “treated as a common thief.” Graham wasn’t perfect (there had been “but one perfect man and He was crucified over 2,000 years ago”) but he had “always intended to remain ‘Honest Horace.’”

Judge Butler had the last word: “The crime of larceny is never committed through innocent mistake.”

The jury took the case at 11:58, went to dinner, and returned for deliberation at 2 o’clock.

An hour later, at 3 o’clock, they reported they had reached a verdict. There was apparently little debate. Graham and his lawyers were called back to the courtroom.

At 3:25 the 12 men filed back into the jury box. Their foreman, H.F. Badger, stated to the clerk “in a quiet voice” that the jury had agreed and their verdict was “guilty.”

According to the Barre Daily Times, Graham “appeared considerably surprised by the verdict.”

“He looked the jury over closely and then seemed to compose himself.”

— ◊ —

— ◊ —

[T]he two years Horace Graham spent awaiting trial and suffering through the ordeal of his conviction — 1919 and 1920 — were also Percival Clement’s two-year term as Vermont’s governor. The reversal of fortune between the two men was complete.

Clement had been right back in 1904, when he sued Graham, demanding to examine the auditor’s books. There had indeed been something amiss in the state treasury. But now those events, and the competition that drove them, seemed of another lifetime.

Just a few months after he took office, on April 17, 1919, Clement wrote Graham a letter, inviting him to Boston for the grand victory parade of the 26th “Yankee Division,” home after 210 days of combat in France.

“You had the honor of sending these lads into the service,” Clement wrote. “I hope you will think it best to come down here and welcome them on their return.”

Graham, still nine months from his trial, declined. “To be frank about it, I cannot afford it,” he wrote, adding that he thought it best “… not to attend any public gathering until my matter is disposed of.”

The day of the parade, April 25, 1919, was bitter cold, spitting snow, but Boston’s streets were thronged with people from all over New England. Bands played at 19 spots along the route, and the crowds sang along, waving flags. Percival Clement watched from the central reviewing stand, alongside Massachusetts’ Gov. Calvin Coolidge.

A flag of honor led the procession, decorated with a single gold star and the number of the division’s dead: 1,587. Next came a piece of artillery, the 220 millimeter German howitzer the division had captured at the Marne, followed by a long column of automobiles, bearing some of the division’s 12,077 wounded soldiers. The victory celebration was tempered by a sober reckoning of the war’s costs.

As governor, Horace Graham had benefited from the wave of patriotism and unity sweeping the country into the war. Percival Clement took office in the war’s aftermath, a more ambiguous time.

One lowpoint came when the National Committee on Mental Hygiene wrote Clement, along with all the country’s governors, asking for help finding employment for veterans suffering from “shell shock.”

“… (O)ur supply of men who are willing for the government to serve them something on a silver platter exceeds the demand,” Clement had replied. “I know of no deserving cases in this state which have not already received careful attention and care …”

A few weeks later, the American Legion held its first conference in Vermont, at the armory in Burlington. Gov. Clement attended and made a speech, and just as he had retaken his seat on the platform, the Legion’s chairman, H. Nelson Jackson, stepped to the podium and directly challenged Clement about the comments in his letter. The papers reported a “storm of applause” from the angry veterans, and when Clement stood again to speak, his “voice shook with emotion as he tried to explain.”

Older politics were also putting Clement on the wrong side of history. He had long opposed women’s suffrage, fearing that women’s votes would push through prohibition of alcohol — the issue upon which he built his whole career. Even after Prohibition became law, in January 1920, Clement had thwarted the effort to make Vermont the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote. Tennessee was left the honor of finally tipping women’s suffrage into law.

He must have had mixed feelings on Nov. 2, 1920, when women voted for the first time across the United States. In St. Johnsbury, more than half of the 1,141 registered women voted before 11 a.m. “(S)everal women brought a babe in arms,” the Caledonian reported, “and there were ladies there to hold the infant while the mother exercised for the first time her rights as a citizen.”

Another potential embarrassment for Clement, and for the state of Vermont, came just two days later. On Thursday, Nov. 4, former governor Horace Graham appeared before the Vermont Supreme Court.

After Graham’s conviction in February, W.B.C. Stickney had filed for appeal, and in October he announced he had found a weak link in the case: one of the jurors, Jerome Stone, the 61-year-old carpenter from Northfield. Three of Stone’s neighbors had signed sworn affidavits that in July of 1919, during the long delay before Graham’s trial, Stone had made comments to them about the case.

“… (T)hey would never get Graham; he will be white washed; he is in the ring and has friends,” Stone allegedly said. Graham was a “damned thief” who was “guilty and ought to go to state prison.”

Stickney argued that because Stone had “formed an opinion” it had been impossible for him to give Graham a fair hearing. He demanded a retrial.

But on Nov. 4, when Graham finally appeared at the Supreme Court, he had no stomach for another ordeal. His counsel admitted that “in the exceptions filed they had only one of any account, and that doubtful.” Hale K. Darling, speaking for his client, asked only that because of Graham’s “long and faithful service to the state,” the sentence be mitigated to a fine.

A jury of 12 ordinary Vermonters had found their governor guilty; now five Supreme Court justices had to decide his sentence. They retired for an hour, then returned to “one of the most tense moments in the history of the court.”

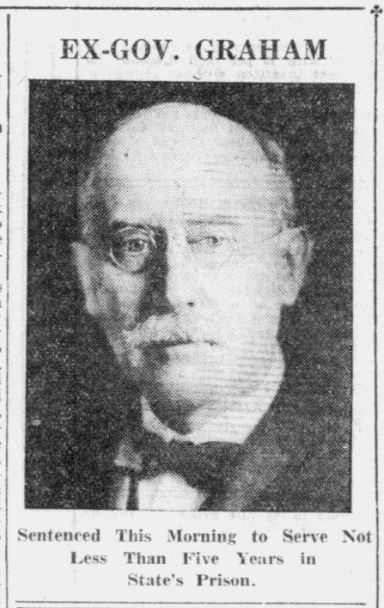

In contrast to his many “composed” appearances, Graham was “pale and nervous.” Asked if he had anything to say before sentence was imposed, he replied, “No, sir.”

Justice George M. Powers announced their verdict. The court had upheld Graham’s conviction and sentenced the former governor to “not less than five years and not more than eight years” of hard labor in the Windsor State Prison.

The judge’s “voice shook with emotion” as he closed the proceedings:

“Mr. Sheriff, the respondent is in your custody.”

Some newspapers rushed to print the news, but Horace Graham did not leave Montpelier. He was permitted to return to his room in the Pavilion Hotel and stayed there, waiting.

Less than two hours later, the announcement came.

“On account of the distinguished service of Gov. Graham to the state of Vermont and the suffering which has been endured,” the official statement read, “I feel that he has been punished enough, and have issued to him a full pardon.”

Percival Clement had rescued his old rival, erasing Graham’s conviction. A number of “prominent men” had gone to visit Graham at the Pavilion Hotel, and when they heard the news “they turned their sympathy into words of congratulation.”

The papers printed the full text of the pardon alongside a “letter” from Clement to Graham, which was in fact a lengthy justification, citing Graham’s leadership during the war and reiterating the logic that Graham had actually been the victim of outdated accounting practices.

Vermonters weren’t surprised by the pardon. The possibility had been debated in the papers for months, and the idea Graham had been “punished enough” appears to have been the prevailing opinion.

Outside the state, however, reactions were less generous.

The New York Times condemned the inequity of Clement’s action: “Thus is warrant given sometimes for saying that there is one law for the rich and another for the poor. …”

And the Boston Transcript noted that Clement’s detailed defense of Graham, in his letter justifying the pardon “… carries the implication that he was without offense.”

“If this were the case, what does justice in Vermont amount to?” the Transcript asked. “Has the Supreme Court condemned an innocent man?”

But after more than two years of scandal, few Vermonters had any appetite for such questions.

“Now let us cast the incident from our minds,” the Orleans County Monitor wrote. “No good can come from its further discussion.”

— ◊ —

— ◊ —

[I]n January of 1922 there were 100 more inmates at the Windsor State Prison than the previous year: 320 men in a facility built for 210. But for his pardon, Horace F. Graham would have worked alongside the other inmates to build new walls, extending the prison’s perimeter to enclose a factory building. He would have worked at a machine while younger men were leased out for road construction, and at night he would have returned to the new, crowded dormitories, to his single cot, one in a long row, to fold his clothes into a cubby along the wall.

Instead he was back with his sister Isabel, in his fine house in Craftsbury, while the state’s lawyers gathered in Montpelier, in the Pavilion Hotel’s ballroom, for the annual meeting of the Vermont Bar Association.

The committee on professional conduct, directed to consider “any conviction of an attorney of an offense involving moral turpitude” as grounds for disbarment, had discovered nine lawyers who had been convicted of crimes. They dismissed eight of the cases, finding no moral failings in the offenses of the attorneys in question.

The last case was Horace Graham’s. The committee had reviewed his case and by a vote of 3 to 2 had resolved “… that by reason of being guilty of this crime his name should be stricken from the roll of attorneys of the Supreme Court.” In one final challenge to his “good name,” Graham stood to be disbarred.

When President Redmond opened the floor for discussion, W.B.C. Stickney, Graham’s lawyer during the trial, argued Graham’s conviction had been “… wiped out by full pardon by the constitutional authority of the State.” He introduced a motion that the association dismiss the case, which was immediately seconded.

President Redmond looked out at the 70 men.

“Is there anything to be said on this matter?”

(The discussion that followed must be read in full to be appreciated. Read Vermont Bar Association 44th Annual Meeting 1922)

Graham’s allies made long speeches. There were quotations from both Shakespeare and the Bible, all in support of his pardon, and the logic he had been “punished enough.”

A Mr. McFarland claimed Graham was still called “Honest Horace” up in Orleans County, and was “… broken in spirit and body, up there on that little farm … waiting for the day when the summons shall call him down to the river across which he must go, never to return.” He asked that the Association not “deliver the death blow to Horace F. Graham.”

Others, like Mr. Healy, were not swayed: “I appeared for two boys who got two years apiece for breaking into a store when they were drunk on liquor, bought from saloons licensed by the State of Vermont.”

Stickney’s most vocal opponent was Harry Shurtleff, from Montpelier.

“The proposition is this: that because somebody can be washed of the offence by a pardon … he should be held as a member of this Bar as though he had done nothing,” he said, indignation rising in his voice.

“(I)f that is good logic and a good principle to follow, for heaven’s sake don’t stop with it here, but teach it in the public schools and defy it from the pulpits.”

When President Redmond finally called for a voice vote, the verdict was unclear. He asked those who were with Stickney, voting to absolve Graham, to stand.

Secretary Hogan surveyed the room. A tense few moments passed in silence as the vote was tallied.

“The count, as I have made it is 37, yes; 34, no,” Hogan reported, “in which I have included my own vote.”

“And so the motion prevails,” added President Redmond, putting the matter to rest at last.

By the slimmest margin, Graham’s name had been cleared.

Harry Shurtleff of Montpelier could not keep silent.

“I think this Association should be consistent and treat all its members alike,” he said, outraged.

“I move that the committee on professional conduct be instructed not to proceed against any member guilty of any offence less than that of Horace Graham.”

The motion was not seconded. A Mr. Porter, who had not yet spoken, had the last word.

“Let us not make a fool of ourselves.”

The meeting adjourned.

— ◊ —

— ◊ —

[H]orace Graham was far from “broken in body and spirit” that spring of 1922. He was 60 years old, healthy, and well-connected. Thanks to Clement, he was a free man. Thanks to Stickney and his allies at the Bar Association, he was able to practice law, earning enough to get by.

He had been humiliated but survived. In 1921 the only trouble had been some discussion in the papers surrounding the annual report from the auditor. In the final calculation, Graham “unlawfully took $26,429.18, and restitution of only $19,880.48 has been made, leaving a balance of $6,548.70 [$140,000 today] yet unpaid and not counting interest either.”

But that was 1921. As 1922 went on Graham noticed that, after all that had happened, he was not in such bad standing. When his name came up in the press, it was usually something remembering the war, and cast him in a good light.

In August he presided over the dedication of a new war memorial, placed in the Common opposite Craftsbury Academy, and that same month the papers reported “rumors” that Graham would be “asked to represent” Craftsbury again in the Legislature. Sure enough, in September Graham defeated a primary challenge from the creamery owner John Dutton and went on the ballot as his town’s Republican candidate.

He received a letter of congratulations from Redfield Proctor Jr., soon to be elected governor. “I have seen only one press comment in reference to your nomination,” Proctor reassured him, “and that was a favorable one in yesterday morning’s Herald.”

In October, shortly before the election, Graham received a letter from Percival Clement, who had himself returned to private life, running his businesses in Rutland. “I doubt if you will have much opposition in your town,” he wrote, “and I am very sure you will be well received in the legislature.”

In November Graham was elected by a wide margin, but he was still concerned enough to write his friend Melvin Morse, a lawyer from Hardwick, about rumors he had heard of an effort to prevent him from taking office when the term started in January.

“I have heard some rumblings along the lines that you suggest,” Morse replied, but assured Graham there was “more smoke than fire.”

It’s unclear just who Graham’s enemies might have been in 1922, but he rejoined the Legislature quietly. The three women taking seats that year attracted more comment.

To the extent they discussed him at all, the papers were kind: Graham’s “service in various positions from state’s attorney to governor has given him an experience and a background which cannot fail to make him a most valuable legislator.” (They didn’t mention his service as auditor.)

He did serve ably, making his impact in the area of school funding, advocating for consolidation of school districts. When his term ended he settled into retirement, remembered in Craftsbury as the curmudgeonly old man who inspired tall tales about his big house. He died, already half forgotten, two weeks before Pearl Harbor, a few months short of his 80th birthday.

In the end, Horace Graham’s story was erased to protect the “fair name” of the state he served. Percival Clement’s pardon spared Vermonters the shame of sending their former governor to jail, and from that moment it was almost like the whole state was keeping a family secret. We glossed over it when we had to, but hardly spoke of him again.

It’s a familiar role for the public, engaged for the moment and quick to forget. The editors of the Bennington Banner might have put it best:

“Only one hundredth part of the voters take interest in politics, to the extent that the whys and wherefores are probed,” they wrote, in the aftermath of Graham’s trial.

“This one out of a hundred points out that the people are easy, they pay their bills, they go to sleep, anything can be put over.”

Part 1 can be read here; Part 2 is here.

Author’s note: I would like to thank Ann Drennan, David Linck of the Craftsbury Historical Society, Paul Carnahan at the Vermont Historical Society, Kurt Pitzer, Mark Bushnell, Glenn Houston, Jeff Tonn, Alice “Stew” Heintz and Katy Leffel for their help and encouragement.