A century ago, Vermont faced its greatest political scandal.

Today it is all but forgotten.

This is the second of a three-part series on the rise and fall of Gov. Horace Graham, by Ben Heintz, who teaches social studies and journalism at U-32 High School in East Montpelier. (Read Part 1 here and Part 3 here.)

[O]n Jan. 4, 1917, the day Horace Graham was sworn in as Vermont’s governor, nine inches of snow fell, fast enough to force the trolley from Barre to cancel its afternoon run. It hardly mattered. The roads were open, and taxi cabs were already undercutting the trolley’s fares.

It was a time of rapid, accelerating change. In 1905, when Graham was 43, there had been just 373 automobiles registered in Vermont; 17 years later, in 1922, there were 37,650. The trolley would soon disappear altogether.

In Graham’s view, Vermont’s governing institutions were also obsolete, and in his inaugural address he outlined a rationale for a new, modern state.

He proposed a single Board of Control, stripping away many of the state’s committees and commissions, cutting superfluous officials, reining in government spending.

“The modern state is a business corporation and should be run as such,” he said. “Individuals, not boards or commissions, should be held to account by the taxpayers.”

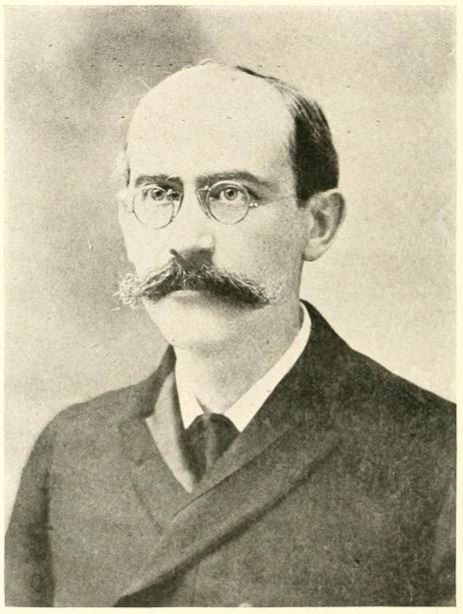

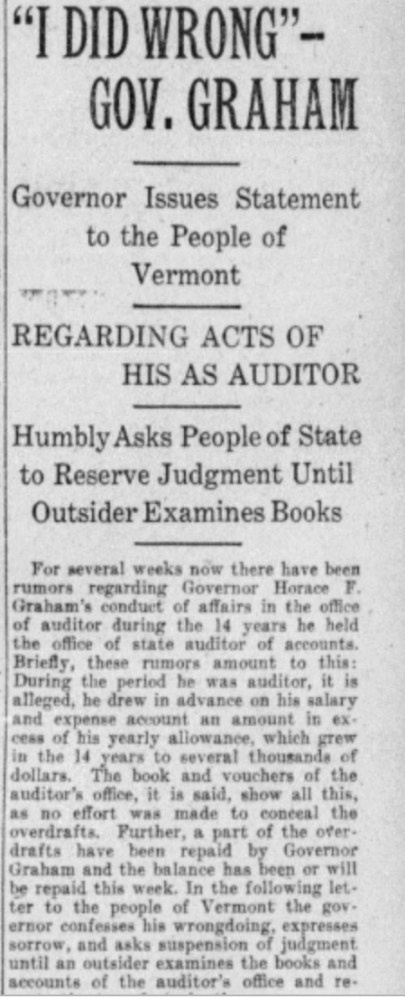

This was a hardline view, coming from a man who had allegedly spent the prior 14 years using his position as state auditor to skim from Vermont’s treasury. Somewhere in the back of his mind he must have known he had taken a risk, leaving the auditor’s office with “discrepancies” on the books, but he pushed the thought aside.

He may have assumed he was unlikely to be “held to account,” or he may have simply been swept up with his plans for the future. This two-year term was not an end in itself. He was already looking past the office, imagining himself senator. The way up the ladder was clear.

— ◊ —

— ◊ —

His mother was born Lucy Fairbanks Swett, in 1835. Her parents named her after a prominent family friend, Lucy Fairbanks, wife of Thaddeus Fairbanks, the inventor and businessman whose family dominated St. Johnsbury for decades. Though her maiden name was Swett, Lucy and her children were later known in Craftsbury as the “Fairbanks Grahams.” There was a ring of aristocracy to the name, even if it had been borrowed.

His father, a New York lawyer named Samuel Hallett Graham, worked as chief clerk for the Assay Office in Manhattan, testing the purity of gold deposits for the Federal Reserve of New York. In contrast to his son, Samuel Graham was known for “averaging many millions yearly without the error of a cent.”

Horace Graham was not a native Vermonter. He was born and spent his early years in Brooklyn. The family summered in Craftsbury when he was young, then bought the house around the time he went to high school.

He must have had a powerful sense of opportunity. When he attended Craftsbury Academy, its principal was George Washington Henderson, a black man and former slave. When he returned to Manhattan to study at NYU and Columbia, he saw the Statue of Liberty rise in New York Harbor and the first electric street lights arrive on Broadway.

It’s remarkable, for such an ambitious man, that Horace chose to return to Craftsbury, going into the lumber business and opening his law practice. He never married, and even as he took statewide office he continued living with his mother and his sister Isabel.

Lucy was a lifelong student of politics, and guests often stopped at the house to discuss public affairs. It seems clear she was Horace’s most important adviser and friend. When she died, in 1915, he was 53 years old and just beginning his campaign for governor.

Presumably she had no knowledge of her son’s crimes, and she never lived to see him disgraced — a measure of mercy for Graham. She does, however, seem to have known about his debts.

Ann Drennan, who lives in the house today, heard that Lucy willed the house to her daughter Isabel, to keep it from Graham’s creditors. According to local lore, Isabel outlived the last creditor by just a few weeks, voiding his claim.

— ◊ —

[T]he Craftsbury house was Graham’s base of operations, but he was a busy man. He worked tirelessly at his consuming interest: political advancement, the game of favors and alliances, forming partnerships, becoming known. He spent time fraternizing at his Masonic lodge, Meridian Sun #20, and traveled around the state for speeches and banquets. As governor he kept a room at the Pavilion Hotel in Montpelier, where he was known for being the first one up in the morning, standing at the doors to the breakfast room, waiting for it to open.

He rose through Vermont’s Republican Party in the era of Redfield Proctor, a former colonel in the Civil War who consolidated the marble industry around Rutland before serving as Vermont’s governor, secretary of war under president Benjamin Harrison, and U.S. senator from Vermont, from 1891 up to his death in 1908.

In 1886 Proctor succeeded in dividing Rutland into two political districts, cutting away the most valuable marble quarries in West Rutland and creating a new town in his name, Proctor, where he owned almost all of the property and most of the voters were his employees.

The Proctors were dominant, but they weren’t unopposed. Their chief rivals in Rutland were the second-richest marble family, the Clements. While Charles Clement’s oldest son Wallace took over operations of the family business, his second son Percival took his first forays into politics, as a fierce critic of Redfield Proctor.

Writing under a pseudonym, “Fabricus,” Percival Clement published “letters to the editor” in the Rutland Herald. In 1886, as Proctor was splitting the town to his advantage, Clement called out Proctor’s ulterior motives: “… to establish a sort of primogeniture system in regard to the office of representative, for the exclusive benefit of the Proctor family and their descendants.”

It was a prescient accusation. Two of Proctor’s sons and one grandson would serve as governor. As he pursued his own political ambitions, Clement would do battle with the Proctors and their allies for the next 30 years.

Horace Graham started without any connection to Proctor, by geography or blood, but by 1902, when he was elected state auditor, Graham had found his place in the Proctors’ orbit, as a lieutenant in what was known as “the Proctor Machine.”

Percival Clement’s collision with Horace Graham came in August of 1904. It was an election year, and that summer the Democrats had found an issue to drive their campaign: between 1882 and 1904, a span in which Vermont’s population barely increased, the state’s government had almost tripled its annual spending.

On Aug. 29, answering the charge of “extravagance in state expenses,” the Republican Party held a rally in Armory Hall in Montpelier. A military band played as the crowd assembled on the street.

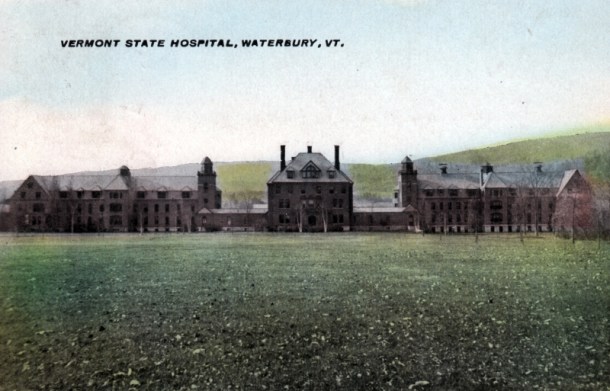

Horace Graham, in his second year as state auditor, was the featured speaker. In his speech he explained that most of the expenses — support for Vermont’s Civil War veterans, for the state’s colleges, highways and libraries — had only recently been taken on by the state. They were the new obligations of a modern government. Care for the insane accounted for the greatest increase: $110,060.90.

“If there is anything in this record of 22 years the Republican party should be ashamed of,” Graham said, “that is a question for the voters.”

These public assurances were ironic: the bank examiner would later testify that Graham had already started stealing from the treasury — $1,100 (almost $18,000 in today’s money) in his first three years as auditor. It was only the beginning, but he was losing his way.

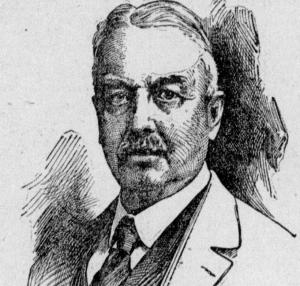

Graham was followed onstage by Percival Clement, then 58, 16 years Graham’s senior. Clement had left his father’s marble company to make his own fortune in banking and railroads before buying his hometown paper, the Rutland Herald, and pursuing a career in politics.

Clement built his political career on a single issue with special resonance for Vermonters: alcohol. As the anti-prohibition, “local option” candidate, he had come within 3,000 votes of defeating the Proctors’ candidate in the governor’s race in 1902, and he attended the rally in August 1904 looking to raise his profile for another attempt.

Clement had a flair for political theater. Though he traveled in a private railroad car, often wearing a large cape, he sometimes referred to himself as a farmer. Taking the podium, he first expressed his pleasure at seeing so many women in attendance, “since each lady controls on average at least four votes.”

Then he turned to the issue of state expenses.

“The gentleman who preceded me thinks we are all right on that question,” Clement said, as Graham looked on. “I can’t agree with him quite.”

“(W)e have been negligent,” he said. “We have not done our full duty in this matter of taking care of the money that comes into our state treasury and that goes out from it.”

This public contradiction was the first shot in a battle. That September Clement demanded that Graham release vouchers (receipts for payment) relating to the state’s hospital for the insane in Brattleboro. He claimed there had been waste and graft, that the records relating to disbursement of state funds were public documents, and that Graham, as auditor, was bound to release them.

When Graham refused, Clement took his case to the Vermont Supreme Court. In Graham’s sworn deposition, he claimed there were more than 145,000 vouchers for state expenses from the past two years, that it would be “… impossible to submit the vouchers to the inspection of every person wanting to see them, and keep them in any kind of order.”

Graham lost the case — the court ruled that “when examination is sought for a public purpose, the interest of a citizen and taxpayer alone, without any other special or personal interest, is sufficient” — but by the time the court finally issued its decision it was another election year, 1906. Clement had moved on, making another run for governor, this time as a Democrat. He did not pursue the matter further.

Graham did not forget. In August of 1906, before a crowd of 1,300 in the Barre Opera House, he took his opportunity to fire back.

“Mr. Clement is parading up and down the state posing as the poor man’s friend,” Graham said. “(W)hen he became president of the Rutland Railroad and found out that the section men were being paid $1.25 a day, he immediately had them cut down to $1.10.”

“Mr. Clement charges that I am no bookkeeper,” Graham said. “But I challenge him to show where one dollar ever got by me that did not have a lawful warrant for its payment.”

The hubris of this statement would one day be exposed, but for the moment Graham was on the winning side. Clement lost his bid for governor again, this time handily, to Redfield Proctor’s eldest son, Fletcher. The Essex County Herald described Clement’s campaign as “… a grand funeral carried out with full honor to his political decease.”

Percival Clement was not easily discouraged. He eventually ran for governor a third time, in 1914. After he lost yet again, in the Republican primaries, he truly looked finished.

But in 1918, as the 18th Amendment moved toward ratification in Washington, the national debate over Prohibition had revived Clement’s career. He was about to announce his fourth candidacy for governor.

The Essex County Herald now described him as having “… entered the arena with his old time vigor and aggressiveness.” He had just turned 72.

— ◊ —

— ◊ —

[S]o it was that Percival Clement was reading with careful attention on Aug. 12, 1918, the day the papers broke the story of Horace Graham’s alleged embezzlement. He could see opportunity in his old rival’s disaster.

That same day, J. Rolf Searles, chairman of Vermont’s Republican State Committee, wrote Clement a letter. Clement, an insurgent in Vermont politics for 20 years, was not well-loved by the Republican establishment. Searles’ letter was a measure of the situation’s gravity.

“The alleged malfeasance in office of one of our prominent officials has undoubtedly come to your attention,” Searles began.

“You are probably also aware that the names of other present and past office holders are being mentioned in this connection,” he wrote, hinting at the larger danger. “The fair name of our party, and of other persons who may be wrongfully accused, demand … that some action be taken to clear up the situation.”

Searles asked Clement to attend a meeting that Friday, Aug. 16, at the Hotel Vermont in Burlington. “I fully realize the reluctance with which you will accept this invitation,” he wrote, “but there are vital interests involved.”

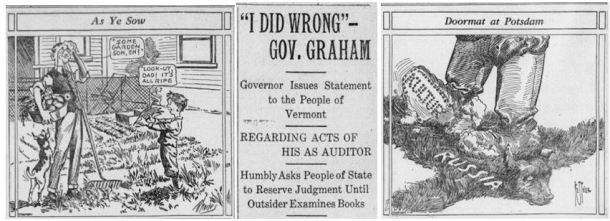

Clement did attend the meeting, along with three former governors, leading Republican lawmakers, and the editors of several papers. The next day the Republican State Committee announced they had adopted a resolution “… that the fair name and reputation of the state of Vermont make it the duty of Governor Graham to resign from his office at once.”

A “subcommittee” visited Graham at his home in Craftsbury and told reporters that “after a long conference” Graham had “promised to resign” by that coming Tuesday, Aug. 20.

We can’t know exactly what he said to the “subcommittee” when they visited him, but a week later he had taken no action, telling reporters he preferred not to discuss the matter. A month later, with no explanation, he was still in office, making appointments, handling the business of the war, acting as though nothing had happened.

Searles and the other Republicans were mystified. Their first effort to make the whole mess disappear, by helping Graham pay off his debts to the state, had failed. It’s unclear exactly who among them contributed money, but it’s safe to say they were all horrified when, even after most of Graham’s debts were mostly repaid, Attorney General Barber had convened a grand jury.

Now, having demanded Graham’s resignation, the Republican leaders expected their “Honest Horace,” who had so loyally served his party for decades, would acquiesce to their demand, uphold his promise, and retreat back to Craftsbury. Instead, defying the most powerful men in the state, Graham remained in office: exposed in the press and attacked by his own party, but still governor.

He adopted a strategy of total denial, making no public comment about his case and fulfilling his duties as though nothing had changed. These tactics might have failed in quieter times, but 1918 was not a normal year. World War I ended that fall, just as another disaster arrived. Almost 2,000 Vermonters died from the Spanish flu, more than three times the number of Vermont soldiers lost in the war.

At the peak of the epidemic that September, the Vermont Supreme Court canceled its October term. A statewide ban on public meetings went into effect, the political season was quiet, and turnout was low in the November elections. Vermonters paid little notice when Percival Clement, stepping into the vacuum left by Graham, easily won the office he had sought for so many years.

In this context, as the grand jury worked in secret to prepare Graham’s indictment, it was easy for for him to stay off the front page. Even when he was forced to appear in court, to hear the 162 charges read against him, he made no comment.

Behind his public composure, however, there is evidence that Graham’s inner life was unraveling. He had spent decades building his good name, as “Honest Horace” and then “Governor Graham.” Now, as his term came to a close, he faced public disgrace.

That December he wrote to an old friend, James Hartness, the wealthy inventor, businessman and future governor. “First, do you think you could find me something in the way of employment, by which I could, for a little at least, live and occupy my mind so as to take it off my troubles,” Graham wrote. Then he made a more direct supplication: “would you feel disposed to extend me some financial assistance until I can get on my feet again?”

This was a diminished Horace Graham, a shadow of the war governor whose letters had so fiercely defended Vermonters. He had refused to resign, but now events were out of his control; his term as governor was ending, and his trial would follow.

He must have dreaded the day, Jan. 9, 1919, when he would have to make his farewell address at the Statehouse, before the Legislature. This was an audience of his peers, the men he had worked alongside and competed against to gain his position. Now, under the shadow of prosecution, he had to stand before them and make an account of his time in office. What had been a low-stakes formality for every preceding governor had for Graham an aspect of ritual humiliation.

Anyone expecting a dramatic statement was soon disappointed. In keeping with his larger strategy of denial, Graham’s speech was entirely conventional, an inventory of accomplishments, ongoing challenges and recommendations, as though his had been a normal term.

The assembled lawmakers, watching Graham rise to meet the moment, were moved to sympathy. As he closed his address, the Burlington Free Press reported, there was “spontaneous applause”:

“It sounded, as it rose and fell, and then rose again in volume as though the assembly of both branches of the Legislature and the spectators were forgetting for the moment everything else, for bidding ‘god-speed’ to Gov. Horace F. Graham.”

The papers were so caught up in Graham’s departure that little notice was paid when, on the day after Graham’s speech, Percival Clement was sworn in as governor. Reporters at the ceremony, looking to give some color to their brief account, seized on the same detail: Clement signed the oath of office with a pen his mother had used for 50 years, made of gold.

A week later, Graham’s exit was still more compelling than anything about the new governor. It is hard to sort out which paper first reported, with a ring of Shakespeare, the remark Graham “was said” to have made after his farewell address:

“I have shown them that I am not a coward, and now it remains to be seen whether I am a knave.”

— ◊ —

(Read Part 1 here and Part 3 here.)

Author’s note: I would like to thank Ann Drennan, David Linck of the Craftsbury Historical Society, Paul Carnahan at the Vermont Historical Society, Kurt Pitzer, Mark Bushnell, Glenn Houston, Jeff Tonn, Alice “Stew” Heintz and Katy Leffel for their help and encouragement.