A century ago, Vermont faced its greatest political scandal.

Today it is all but forgotten.

This is the first of a three-part series on the rise and fall of Gov. Horace Graham, by Ben Heintz, who teaches social studies and journalism at U-32 High School in East Montpelier. (Read Part 2 here and Part 3 here.)

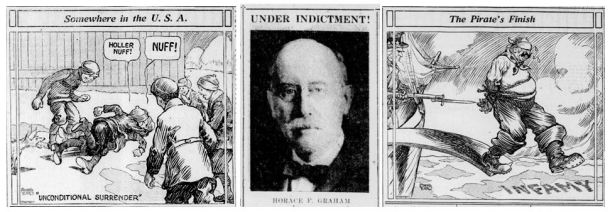

[O]ne hundred years ago, at 2:15 on the afternoon of Wednesday, Nov. 20, 1918, Gov. Horace F. Graham arrived with his lawyers at the four-pillared, brick courthouse in Montpelier. He climbed the curved stairway to the second floor, and walked to the front of the courtroom, passing the bar to take his seat.

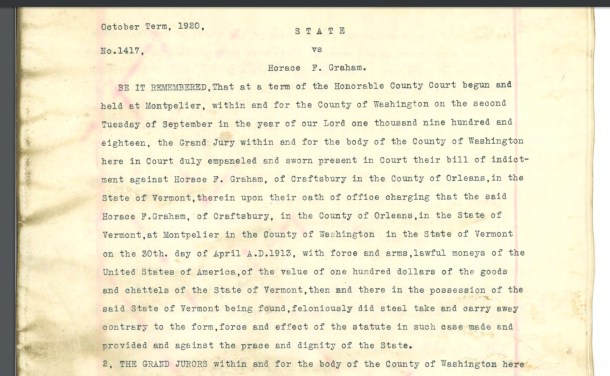

He had been here many times as an attorney, but on this day, in a bitter reversal, he was appearing to hear his own indictment. A grand jury was charging him with 152 counts of larceny and 10 counts of embezzlement from the State of Vermont.

The situation was surreal, for all parties. The state’s attorneys had been unsure whether they could serve a warrant to a sitting governor. Graham had never been arrested, and carried no official papers to the summons.

Horace Graham was a Vermont institution. He was 56 years old, a lifelong bachelor, balding, with a neat gray moustache and wire-rimmed spectacles — the embodiment of sober, frugal Vermont republicanism. He had held public office more than 20 years, and as governor he led Vermont through World War I. Vermonters called him by his nickname, earned through his long and scrupulous service to the state: “Honest Horace.”

The charges dated from Graham’s years as state auditor, from 1902 up until 1916. He had routinely paid out state money for road building and other projects, but sometimes he left sums unaccounted for, with no “vouchers,” or receipts, to prove the money had reached the contractors. It was a classic case of “skimming:” each alleged theft was small relative to the volume of money Graham handled, but over 14 years they amounted to $25,000 — around $450,000 in today’s money.

Graham was not called upon to speak in court that day. He listened as the charges against him were read, then his lawyer, Rufus Brown, requested that the trial be delayed a few months, until March of the following year, and was granted the continuance.

There were few onlookers in attendance, and the business of the court was strangely matter-of-fact.

Two of Graham’s friends — Frank Corry, owner of the First National Bank, and H.W. Varnum, a quarry owner — went with Graham to the clerk’s desk, where each signed a surety for a $5,000 bond.

Vermont’s governor had just been indicted by a grand jury, but the handful of reporters in the courtroom that day could make little of the spectacle. “After visiting for a short time with several persons in the courtroom,” the Barre Daily Times reported, “Governor Graham went back to his office in the State House.”

Graham refused to make any comment, before or after his appearance in court. Some reporters resorted to quoting his only official statement, from three months earlier, on Aug. 12, 1918, when news of his “alleged malfeasance” first broke in the papers.

“I realize that I did wrong,” he had written, “and for this I am extremely sorry.”

This apology had been confusing from the start. In that same official statement, Graham had also insisted on his innocence. He had never sought to conceal the shortages, he wrote: the books “always showed … just how my salary and expense account stand.”

Some of the first editorials tried to rationalize the alleged theft: the governor had been “… a victim of a system that makes it easy for an officeholder to divert public money.” But Graham’s story didn’t add up. More than $20,000 taxpayer dollars had gone missing in his custody, at a time when the average farm was worth about $5,000. It was far more than the occasional mistake could explain.

And there was another odd fact. The papers stressed that Graham had already “restored” most of the money to the state. But if he hadn’t stolen the money, why was he paying it back?

Worse still, there were rumors (later proven true) that Graham had not come up with the money himself. A mysterious, unnamed group of prominent Republicans had conspired to “make good the shortage in Graham’s accounts” immediately after they came to light, before the public knew anything, and before the Attorney General could bring charges against Graham. Who were these men? And why were they so desperate to save him?

Gradually the facts sank in. Under the heading “A Tragedy,” the Brattleboro Reformer admitted that “… regardless of any explanation which may be made, Horace Graham is dead politically.”

In fact, Graham had plenty of life in him. For the next 27 months he would fight — in the courts, in the press and behind the scenes — to save his good name.

— ◊ —

— ◊ —

[I]t is no accident that few Vermonters have heard of Horace Graham. The story is an ugly mark on our state’s proud political narrative, suppressed in our collective memory. The elites of the Republican Party worked to sweep the affair under the rug even as it was happening, and the public moved on, happy to forget. Even nature played its part in the conspiracy: the transcripts of Graham’s trial, like many others, were lost in the 1927 flood.

Graham’s obituaries either ignored or barely acknowledged the scandal. The Burlington Free Press mentioned “financial difficulties” that “caused him much worry,” but assured readers that “… the majority of Vermonters indicated their belief in him.”

After a century of silence around Graham, his story is conspicuously absent from Vermont’s popular history. Our most comprehensive recent history book, “Freedom and Unity,” gives the scandal a sentence or two, as does Samuel Hand’s survey of the Republican Party’s rise and fall in Vermont, “The Star That Set.” State Sen. Bill Doyle’s excellent book, “Vermont’s Political Tradition,” details the elections and governors leading up to and following Graham, but omits him entirely. The most thorough account of Graham’s life appears to be the 20-page paper Mary Ann Merrill wrote for professor Nicholas Muller’s Vermont History class at the University of Vermont in 1970.

Daniel Metraux, who included a brief but careful discussion of the scandal in “Craftsbury: A Brief Social History,” from 1975, was right to conclude that Horace Graham “remains one of the real enigmas of Vermont history.”

There are still traces of Horace Graham, however, in his hometown of Craftsbury.

His most enduring legacy is his house, which still stands, about halfway up the road from Craftsbury village to the Common. The original farmhouse was simple, set back from the road, with an ell that connected to the barn. The larger part of the house, which Graham built, is more ornate, in a kind of Queen Anne style, with long porches running around the sides and a tower overlooking the road.

Ann Drennan, a retired teacher, has lived in Graham’s house almost 40 years. One story is that Graham poured the money he embezzled into its renovations, and Drennan calls the place, with a hearty laugh, “The House Vermont Built.”

It is mostly unchanged from his time. His cast iron cook stove still stands in the kitchen, piled with mail. Drennan’s bedroom, the “tower room,” was once his office.

Contractors working on the place told Drennan that the house, for all its grandeur, trimmed in curly maple from Graham’s sawmill, actually “wasn’t well put together.” The construction above ground was fine, they said, but the foundation and substructure were built on the cheap, cutting corners. She’s had the house jacked up three times for repairs.

In 1993 Drennan was bedridden for 14 weeks with a broken back. She set out to research as much as she could about her house and Horace Graham, in an effort to qualify the dilapidated barn for restoration by the state. When she asked the town elites about Graham, and mentioned his alleged crimes, they “did not take kindly,” and gave her the cold shoulder. Other townspeople, however, were willing to speak.

Some of the old-timers remembered Graham in the 1930s, when they were young and he was in his 70s. In those years he was rarely seen publicly except in his official roles, on the school board, officiating at ceremonies, etc. Earle Wilson, who succeeded Graham as town moderator, remembered Graham as “one of the best parliamentarians I ever knew” but also “a very sarcastic man” who could be intimidating. When Graham ran the meeting, Earle said, “the common person didn’t dare speak.”

In his last years Graham was reportedly a “curmudgeonly old fellow.” One old man told Drennan about a time, driving his “tin lizzie” up the hill past Graham’s house, when the car broke down and drifted to a stop in Graham’s driveway. Graham came out right away, incensed: “This is no parking lot! Get that out of here!”

He was aloof from the day-to-day operations of his businesses. A man who had worked for Graham at his sawmill said Graham “knew nothing about wood” and another man who had been the hired man at Graham’s farm said he “knew nothing about dairy farming,” but had a good sense of humor once you got to know him. The hired man said he had once directly asked Graham about his alleged embezzlement, and Graham firmly denied it, saying he “took the fall because it happened on his watch.” The hired man said he believed Graham.

For years after his death Graham was an outsized figure in town lore. There were ghost stories — Graham’s sister Isabel moved about the house at night — and other fantastic rumors. He had killed a couple of men and buried their bodies in the basement. He had a stockpile of cash hidden somewhere in the house.

Though her own house guests have reported seeing ghosts — a girl walking the upstairs hallway in an old dress with leghorn sleeves, or crying, coming up the stairs — Drennan herself has never heard or seen anything strange in the house. “I guess I just don’t have the imagination for it,” she said. Still, Drennan admitted that when she was told the house’s basement needed to be dug out to repair the foundation, she dragged her feet, some part of her dreading they would find human bones.

Mixed among the fantasies Drennan occasionally found clues to the real story. One older woman, whose family had been close to Graham’s, told Drennan she had heard Graham embezzled because he had gambled away his money on the stock market. Others said he had indebted himself pouring money into the house. Drennan’s interest was piqued, but there were a lot of dead ends. Her application for state funding to save the barn was a finalist that year, but was not chosen. When her back healed she moved on, and the barn fell down.

Drennan is a confessed “accumulator,” and her notes from 1993 are buried somewhere in Graham’s house. She says that on a sheet of paper in one of her boxes she has the names of the three Craftsbury men — “a doctor, a lawyer and a businessman” — who were said to have paid Graham’s debts to the state. “He never paid them back,” she says.

Once, on a field trip with her students in the mid-80s, Drennan noticed that Graham is the only former governor with no portrait in the Statehouse. Today Drennan “isn’t getting any younger” and wants to see Graham’s portrait hung before she “is no more.” She isn’t defending Graham — she thinks he probably stole the money. She just wants him to have his place in the story, warts and all.

On the field trip she asked the sergeant-at-arms why Graham had no portrait.

“That old sinner?” he replied, laughing. “We’ll never show his face here.”

— ◊ —

— ◊ —

[A] painted portrait would add little to our knowledge of Horace Graham. He left little of his inner life in the historical record, and the details we have suggest a complex man, resisting simple definition.

If he was a thief, he was also a sincere and hardworking public servant. It’s impossible to know why he remained a bachelor, but the most likely explanation, given the evidence we have, is his near-fanatical commitment to his work.

As governor during World War I, raising armies and managing new logistical challenges in addition to the regular business of the state, he somehow found time to answer hundreds of letters from ordinary citizens. His replies, seeking to help Vermonters of all stripes, help to explain his stature across the state in 1918.

When the draft came, he helped some farm families keep their sons home. When a mother wrote him for help after her daughter “kept company with an Uncle Sam’s man” and became pregnant, Graham arranged for the soldier’s commanding officers to set the boy straight, making him promise to marry the girl and securing a leave for him to come home for the wedding.

One letter in particular gives a sense of Graham’s intellect and character. He received an inquiry from the War Department concerning a Vermont man who had served as an officer in the British military before the U.S. entered the war, then came home in 1917 seeking a commission as an officer in the U.S. Army. When the man appeared at the War Department in Washington, D.C., the officials had been impressed by his record, but liquor had been “detected on his breath,” leaving “a very unfavorable impression.”

Graham’s response:

I am not, of course, going to enter into any argument on this case but I am free to confess that I doubt his breath is the only breath in the service that ‘smells of rum.’ I have had the good, or ill, fortune to become acquainted with several distinguished breaths in the last six months, and their owners seem to know a ‘horn of good stuff’ when they saw it.

I have seen quite a little of ———– since he came to Montpelier, after his return from France, and I have never seen any indication of liquor about him or smelled it upon him. I have met him in the hotel, on the street, in the club and in my office.

I would not have you understand that I have any reason to think that he does not imbibe occasionally, but I do not believe he gets drunk or loses his head. If you and I had been two years in France, I think perhaps we might on occasion take a drink, perhaps two, maybe three.

Whatever the final decision in the matter is, I think he ought to be advised right away…. He seems anxious to get back into the service and to prefer active work. I take it he would rather serve his country behind a parapet than behind a desk.

To return to the rum question again, I think it was Lincoln who was very anxious at one time to learn the brand that Grant used so that he might send some to all of his generals.

I know you will do what you can consistently to set our friend going again and I hope to hear from you further.

The man received his commission.

Graham possessed the independence and courage Vermonters have always celebrated in their leaders. Were it not for his scandal, he was on track to represent Vermont in Washington, D.C., as Sen. Horace Graham. His name might have been remembered in Vermont alongside George Aiken’s, or Sen. Ralph Flanders, who led the effort to censure Joseph McCarthy during the Red Scare in 1954.

In fact, according to one story that came out after the war, Graham had been willing to defy the federal government to protect another man’s good name. This was during the original Red Scare, fueled by fears of “bolshevism” and labor unrest surrounding World War I, when Graham was governor. One of the many Americans blacklisted by the FBI was a Vermonter, the Rev. Frazer Metzger, who was probably targeted because he had once run for governor as a progressive. His name, both German and Jewish, couldn’t have helped.

Metzger was Randolph’s state senator in 1918, and served in a special wartime position as “director of food production and conservation.” When he was blacklisted he asked the governor for help.

On Graham’s next trip to Washington, he visited the Department of Justice and persuaded an official to retrieve Metzger’s file. After a long wait, the file was produced, and Graham read through to the last sentence: “He is a German spy.”

Graham turned the file over in its folder. On the back of the last page he wrote, in pen: “This is all a damned lie,” and signed his name: “Horace F. Graham, Governor of Vermont.”

By the summer of 1918, when his scandal broke, Graham had earned Vermonters’ respect. Under the “mountain rule,” sharing power between the eastern and western sides of the state, Vermont’s governors traditionally served just one two-year term, but that summer there was a drumbeat of calls for Graham to be “… drafted, if there is no other equally good method of securing him,” to stay on for another term.

Even after the scandal broke, as the evidence mounted against him, many Vermonters believed Graham’s service to the state outweighed his transgressions. The Randolph Herald and News expressed a common judgment:

“The public strikes a mental balance in the case of Mr. Graham — so much for him, so much against him,” they wrote, “and it cannot find, surveying that balance, that he is entitled to a felon’s cell.”

Other Vermonters rejected this logic. For some, the principle of equality was at stake. Graham should have “full justice,” as the Swanton Courier put it, “… just as it would be meted out to an obscure, wayward bank teller.”

The scandal also threatened Vermonters’ exceptionalism. Maybe, in an age when corruption was rampant across the nation, we were more like everyone else than we wanted to admit.

As one writer observed in the Burlington Free Press, not only Graham “… but also the people of Vermont were on trial.”

“It was an unfortunate case where either one or the other must stand convicted.”

(Read Part 2 here and Part 3 here.)

Author’s note: I would like to thank Ann Drennan, David Linck of the Craftsbury Historical Society, Paul Carnahan at the Vermont Historical Society, Kurt Pitzer, Mark Bushnell, Glenn Houston, Jeff Tonn, Alice “Stew” Heintz and Katy Leffel for their help and encouragement.