PUTNEY — The late governor turned U.S. senator George Aiken — the man behind Vermont’s green license plates, the term “Northeast Kingdom” and the oft-paraphrased call for the nation’s Vietnam War leaders to “say we won and get out” — was reflecting on his 90th birthday in 1982 when he sat on his Putney Mountain porch and surveyed his hometown below.

“My birthplace has been torn down, and there’s a $7 million marker over it — call it Route 91,” Aiken told the press at the time. “I go down to Putney Village now and I don’t know one person in 10. There’s so much goddamn intellects coming in from outside, I can’t keep track.”

Aiken referred to “that fella who wrote that bestselling book” (John Irving, author of “The World According to Garp”), although he could have been talking about many of the students and staff at such private institutions as The Putney School, where several Kennedys have graduated; The Greenwood School, where Ken Burns filmed a documentary; and the former Windham (and now Landmark) College, where Irving once taught English.

Aiken was more familiar with the working class, be it at his Main Street greenhouse or Putney’s largest and longest-operating industrial employer, its central downtown paper mill. Founded in the early 1800s, the plant has weathered changes in organization and ownership — most recently as the Soundview Paper Co., maker of Marcal towels and tissue — to become the community’s sole manufacturing survivor.

That’s why this month’s sudden closure took so many locals by surprise.

“There’s always been a tension between the people who were born and raised here and understand how the mill has been the lifeblood for so many, and the folks who didn’t like the smell of sulfur and wished it would go away,” said former Gov. Peter Shumlin, the other Putney resident to serve as the state’s chief executive. “But it’s what made Putney a community instead of just a commuter town.”

Shumlin, who started in politics by winning a local selectboard seat at age 24, received a call from Soundview President Rob Baron last week at the same time 127 employees were informed of the shutdown.

“He made it very clear they intend to continue to pay property taxes and work together to try to find a solution that doesn’t just leave a hole in the center of town,” Shumlin said. “I asked the obvious question of, ‘Can’t you sell it instead of closing it down?’ He told me all the reasons why that wasn’t going to work.”

Shumlin, who now co-directs his family’s Putney Student Travel company, hung up with a reluctant understanding: A large urban corporation focused more on profits than on the past doesn’t see an economic future in a small rural community.

That leaves residents with a question of identity: Does a town that prides itself on progressive thinking still hold a place for everyday workers?

‘The greatest development Vermont has ever seen’

The Putney Historical Society book “Putney: World’s Best Known Small Town” — the title comes from Aiken’s public description of his home — recounts the community’s evolution, starting with the days when Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys arrived in 1779 to quell a group of New York-supporting settlers.

I myself rewind to 1900, when my grandfather David Hannum Sr. was born on a Putney dairy farm that wasn’t wired for electricity until he was 14. Delivering mail as postman on the town’s first rural delivery route, he went on to work at the local Green Mountain Orchards, all the while marrying my grandmother — local one-room school teacher Rhona Patterson — and buying property where they’d live until their deaths well into their 90s.

With families rooted in town for generations, everyone was connected to everyone. Aiken, for example, planted the first apple trees at the orchard (still run by the founding Darrow family) and played a card game called “whist” with my grandparents (a winning hand when you’re a reporting intern seeking to interview a birthday-celebrating political legend for your first-ever story).

“We’re on the verge of the greatest development Vermont has ever seen,” Aiken said at the 1961 local opening of Interstate 91. Soon after, the town’s population more than doubled (currently it’s 2,617) since the turn-of-the-century day when a 9-year-old Aiken heard a neighbor gallop along dirt roads to holler that then-President William McKinley had been assassinated.

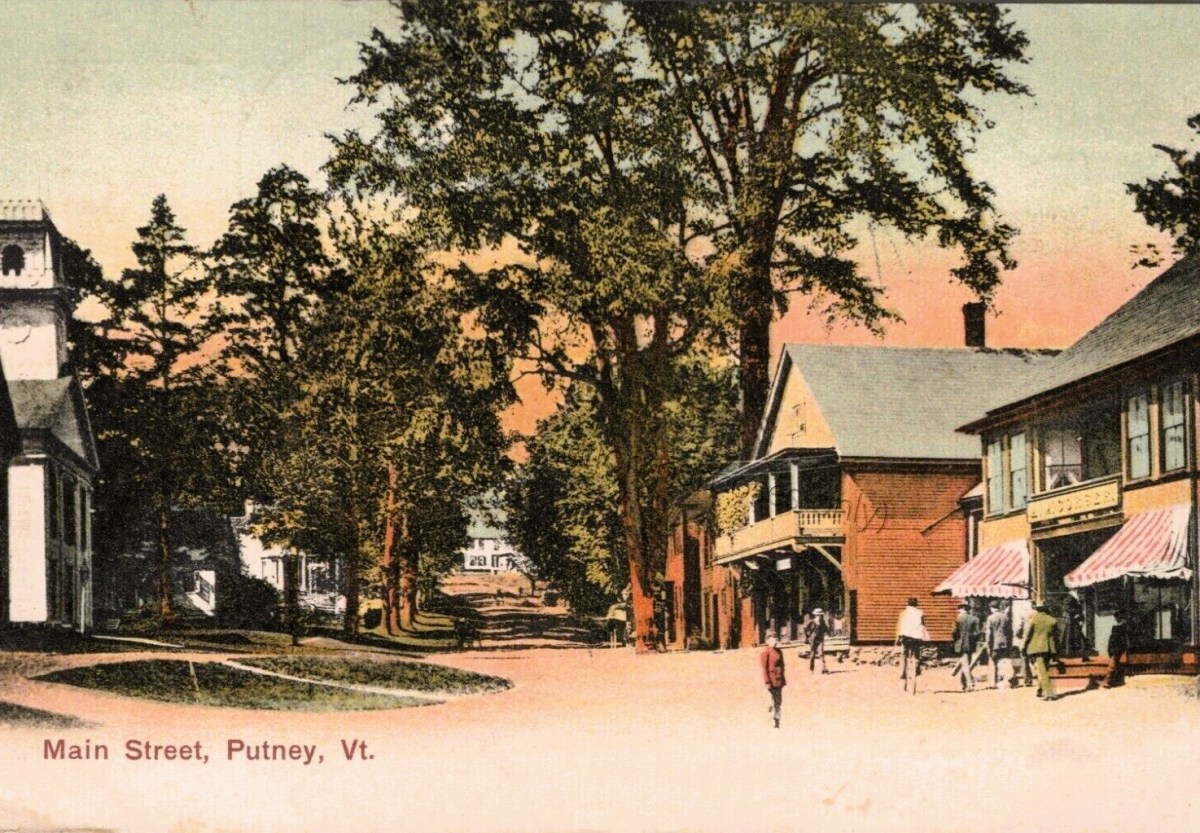

Although Main Street’s central square looks almost exactly as it did a century ago, the 1791 Putney Tavern now hosts a farm-to-plate restaurant and such wellness practices as acupuncture and qigong. Nearby, the former Federated Church has become the Next Stage arts center, while the old Basketville storefront is shared by a Waldorf-inspired curriculum consultant and local-fruit winery.

Today, the town is “best known” for its private schools and art studios; athletes ranging from 95-year-old Olympian John Caldwell (a pioneer who literally wrote “The Cross-Country Ski Book”) to current two-time Paralympic cycling medalist Alicia Dana; and 1997 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Jody Williams, the anti-landmine activist who was sleeping at her onetime Putney home when she learned of her win at 4 in the morning.

Yet amid two world wars, the Great Depression and waves of societal change, the paper mill stayed put and productive. Long-timers most remember it under the leadership of Polish immigrant Wojciech Kazmierczak and daughter and son-in-law Shirley and Earl Stockwell, who owned it from 1938 until selling to the first of several out-of-state operators in 1984.

“They had third- and fourth-generation employees,” Shumlin recalled, “and when someone’s son, daughter, cousin, uncle or aunt needed work, all they had to do is go see Earl or Shirley and they had a job.”

Those workers, in turn, walked next door to the Putney General Store or drove their cars down the street to places like Rod’s Towing & Repair, where three generations of the Winchester family have labored since 1967.

“One of the guys who works at the mill has been telling me for the last six months that he saw it coming, and I didn’t believe it,” said Rod’s son Greg, who now runs the service station with his two daughters. “But what’s the reality? There used to be paper mills up and down New England that are gone.”

‘We’re going to have to think outside the box’

The mill shutdown comes a year after the town held a series of “Our Future Putney” meetings under the guidance of the Vermont Council on Rural Development.

“With a large number of schools, a thriving local arts and performance center, and many successful businesses and community organizations, Putney has a vibrant future, and a strong system of community support to realize its goals,” the effort’s final report concluded.

That said, even the most enthusiastic of meeting participants have been thrown by the closure. Take resident Lyssa Papazian, a historic preservation consultant. When she and fellow members of the Putney Historical Society saw the 1796 general store go up in flames in 2008, they raised upward of $1 million to bring it back to life.

Undeterred after the restored structure burned down again just before its scheduled 2009 reopening, the historical society reaped enough insurance money to rebuild once more. Then the new storekeeper died of cancer, leaving Papazian and other volunteers to run the business until finding new operators in 2019.

With such history, Papazian knows repurposing an aging paper mill won’t be simple — especially given that the historical society has its hands full planning a $2 million renovation of the 1871 Town Hall.

“It’s hard, because it takes a long time to do a project,” Papazian said of any type of revitalization. “We know it’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon.”

Then again, the “Our Future Putney” meetings have sparked new life into the recently dormant nonprofit corporation Discover Putney, which is set to form a board of directors and several committees to promote local business.

“Many of us are hoping the effort can harness an awful lot of really amazing resources and energy in this town,” Papazian said. “But you can’t wave a magic wand and immediately make things happen.”

Reporters have wandered about Putney in the past week seeking to interview laid-off workers. Locals, in response, haven’t offered names, noting that everyone is still processing the news.

At the general store, a bulletin board features want ads for a farmhand and yarn-spinning apprentice (the pay of $16 to $17.50 an hour compares with the mill’s average starting salary of $20 an hour), while a poster advertises openings at $21 an hour and up at the C&S Wholesale Grocers warehouse eight miles south in Brattleboro.

The potential loss of workers bothers many residents who talk on the streets and on social media about how the mill diversified local opinion and, in the words on one Facebook commenter, “kept Putney real.”

“What worries me is that working-class, libertarian or conservative perspectives may have just been minimized,” said Meg Mott, a former Marlboro College political theory professor turned Putney Town Meeting moderator. “If we only have progressive voices, just as other parts of the country only have conservative voices, then people’s biases get reinforced, policy tends to be more exclusive and thinking tends to be more extreme.”

At Rod’s, Greg Winchester expressed concern but not fear. He noted that after a 2021 arson fire destroyed his service station, the community raised $50,000 to help his family rebuild.

“When I was a kid, you did your shopping downtown, then everybody went to the mall and now the internet has put them all out of business,” the 55-year-old said. “That’s life. Everything changes, and you have to adapt. This is going to sting, everybody’s going to feel it, and we’re going to have to think outside the box. But we’ll survive it, because people are invested in this town.”

Clarification: This story has been updated to clarify that the Putney Paper Mill is the largest industrial employer in the town.