As usual, redrawing the Vermont Legislature’s district maps is fraught with complications.

A committee of seven former legislators and party representatives is working on the redistricting, a process that occurs every 10 years, based on federal census results.

As the Vermont population shifts, the Legislative Apportionment Board must change the map to make sure the size of each legislative district falls into line with the U.S. Supreme Court’s one-person, one-vote rule. That includes the districts for all 150 House members and all 30 state senators.

It’s a process that board President Tom Little likens to a children’s sliding tile puzzle, where moving the borders of one district can end up changing everything around it.

“It’s time-consuming, and you have to do it sort of by trial and error,” said Little, a lawyer and a former state legislator.

Not only do board members have to keep each district the same population size, but they also have a constitutional obligation to follow town and county lines when possible and make the districts “geographically compact” — that is, not bizarrely stretched or slim.

But interest groups and a survey of Vermonters have asked the board to consider another preference: limiting the number of multimember districts — ones that have two or more legislators for a single district.

Ten of Vermont’s 13 Senate districts and 46 of Vermont’s 104 House districts have two or more legislators. Three Senate districts have three senators, and one district, Chittenden, has six senators in total.

Those districts tend to be in Vermont’s more urban areas, such as the Chittenden Senate District, which includes all of Burlington and many nearby towns. Opponents of multimember districts say they create a skewed representation of those regions.

“It leads to the perception, if not the reality, of unequal representation in Montpelier,” said Tom Hughes, senior strategist at the Vermont Public Interest Research Group. Hughes spoke in favor of single-member districts during a board meeting in mid-September.

“If a person can call on eight senators and representatives, they have more people in Montpelier looking after their interests than the people who can only call two people in Montpelier,” he said.

Advocates of single-member districts also say they are easier to campaign in and represent since there are fewer people in the district to reach. Rob Roper, a board member who was once chair of the Vermont Republican Party, said it was harder for him to recruit candidates to run in multimember districts.

The Vermont public appears to agree with Hughes and Roper. In a board survey of more than 600 people, 75% supported single-member House districts. About two-thirds said they would be willing to split up towns to create single-member districts.

“Some of us ‘smaller’ towns don’t have much of an opportunity to be heard from, once our smaller 200-400 person towns get rolled in with a 5,000-6,000 person town,” one person responded to the survey.

“Then the most populated counties cannot run roughshod over the least populated counties,” another wrote.

But there’s a difficulty in creating districts, one that wasn’t discussed as much in the latest board meetings: Where people live isn’t neutral.

“The most fundamental problem is that we base representation on place of residence, rather than on interest or partisanship,” Dartmouth College policy researcher Linda Fowler said. “And [right] now, party is highly correlated with place of residence.”

It’s easy to use that trend “to gerrymander people into permanent minority status,” Fowler said.

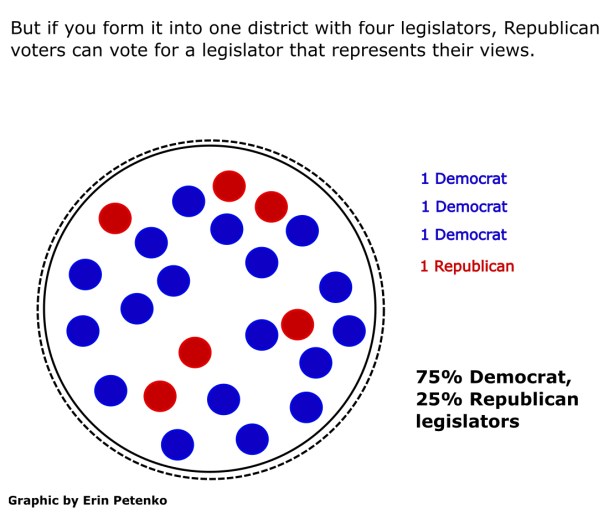

She believes that multimember districts are a way to balance districts not just by population, but by partisanship, to create truly competitive districts rather than easy wins for each party.

How to make a fair district

Fowler co-wrote a piece for The Washington Post in July, explaining why multimember districts may be more fair and competitive.

“With fewer and fewer politically diverse communities, state legislators find it easier to pack their opponents’ voters into a single political district — called ‘packing’ — or to dilute their votes by dispersing such communities into many different districts — called ‘cracking,’” she wrote.

In contrast, multimember districts give more leeway for minority parties to gain traction among a larger coalition of voters. (See the graphic below for more details on how that works.)

Not only do bigger districts limit gerrymandering, “the bigger the unit of analysis, the more likely it is to be diverse,” Fowler said in an interview with VTDigger.

“And the smaller the [district], the more likely it is to be homogeneous. So if it’s homogeneous, it’s not going to be competitive,” she said. That means candidates running in those bigger, more diverse districts have to find a way to appeal to a broad coalition of voters, rather than a partisan base.

“Extreme Republicans and extreme Democrats — and there are plenty of both — they never have to explain themselves to anybody who disagrees with them because they come from a small, homogeneous community and everybody thinks alike,” she said.

She said there’s some reason to believe Vermont’s political structure disadvantages minority party candidates. The state reelected Republican Phil Scott with 67% of the vote in 2020, yet Republicans hold only 23% of the Senate and 31% of the House.

Who has the advantage?

A VTDigger analysis of legislative data shows that there’s reason to believe single-member districts put Republicans at a disadvantage.

Digger reviewed districts that changed from single-member to multimember, or vice versa, in the 2010 redistricting process. Nine House districts gained a seat, and seven House districts lost a seat in 2010.

When those House districts had one seat, Republicans held 26% of terms served from 2003 to 2021. When they had two seats, Republicans held 38% of terms. It’s unclear how the change affected third-party candidates.

It’s a relatively small sample size, and there may be other factors at play such as changing district composition. But it may support the idea of the board considering the role multimember districts play in creating a fair map.

There’s currently no Vermont mandate for the board to consider partisan fairness when creating the district map.

“The emphasis ought to be on trying to create as many competitive districts as possible,” Fowler said.

“When you have districts with permanent minorities … those races are frequently uncontested,” she said. “In uncompetitive districts … it’s hard to get quality candidates to run. It’s hard to get donors and volunteers to support them. And so, the district sort of becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Too large or too small

At an Oct. 4 meeting, board members shared their draft maps for the counties they’re working on. Some board members had the goal of creating all single-member districts, or as many as possible.

A lot of changes had to be made. Four Senate districts were too large or small in population and needed to be adjusted, which could affect the surrounding districts, too, according to an analysis from the Vermont Center for Geographic Information.

Twenty-one House districts were too large or small, according to the analysis.

But Little told VTDigger there’s historically been a certain amount of “inertia” to making significant changes in the district map, particularly when it affects an incumbent, making it difficult for single-member suggestions to become a reality.

“If you said … ‘Let’s have Senate districts that are no more than one or two [senators],’ you would inevitably be affecting incumbents,” he said.

After board members draft their suggested map, they plan to send that draft to local governments for review, then present their suggestions to a legislative committee to draw up the final map.

Shap Smith, the former speaker of the House, oversaw that process for the 2010 census results. There was “a fair amount of bipartisanship in the overall plan,” he said, but the people drawing the districts don’t want their districts to change.

He also said the reality of population distribution makes it difficult to live up to the “philosophical goal” of single-member districts without splitting up towns, which “doesn’t go over very well” with the towns.

Little said that, in 2010, the board voted in favor of a House map that had all single-member districts — but criticism from the towns made the board back off that idea.

In the “laborious” process being undertaken now to create a new district map, he’s in favor of trying to get single-member districts again — as long as the map still meets the requirements of being compact, following local borders and being equal in population.

“If we come up with a plan that does those things and has more single-member House districts than we currently have, I'm perfectly OK with that,” he said. “Where I draw the line is against elevating the single-member district priority above what's in the constitutional statutes.”

Correction: This article has been updated to correct the number of Legislative Apportionment Board members.