Every spring, the Bicknell’s thrush, a small, brown songbird in the robin family, takes flight from its winter grounds in Hispaniola and Cuba to make a nearly 2,000-mile journey back to the tallest peaks of the Northeast.

There, perched on the top of the toll road at Mount Mansfield for an overnight trip each summer week, Chris Rimmer, director of the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, waits for the bird to grace his mist nets. He’s been studying the Bicknell’s thrush for around 30 years.

Over time, Rimmer has become increasingly aware that the fate of the Bicknell’s thrush may be heavily influenced by climate change.

As the climate warms, evidence suggests that some of the scrubby vegetation of Vermont’s mountaintops — particularly the balsam fir — could be imperiled. Warming temperatures may also invite nest predators, such as red squirrels, into the upper reaches of Vermont’s forest.

Populations of Bicknell’s thrush have declined steeply in Canada since the 1960s and are listed on the conservation group Partners in Flight’s “red watch” list, which means they live in restricted habitats and have small, declining populations. While the bird is listed as “threatened” in Canada, it is listed as “vulnerable” in the U.S.

With all of its vulnerabilities, the Bicknell’s thrush could be seen as a canary in the coal mine for climate change in Vermont — one of the species to be pushed out as conditions take a turn.

It isn’t just Vermont conditions that are affecting the bird. The thrush also faces habitat loss and deforestation in its wintering grounds in Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

“Some predictive studies of global climate change indicate the loss of more than half of Bicknell’s breeding habitat by 2038 and the loss of more than 90% by 2100,” said Cornell University’s bird identifying website, All About Birds.

Absence of local breeders

In the first week in August, scientists from the Vermont Center for Ecostudies drove up Mount Mansfield’s windy Toll Road to set up for the night, about 4,000 feet above sea level.

Along with a gaggle of fellow scientists and interns, Rimmer ascended into the trees to set up a series of mist nests, like 6-foot-tall volleyball nets whose mesh is so fine it was almost invisible.

The nets caught the birds while they were flying through the forest, and the scientists checked every hour, extracting them with delicate protocol. Typically, during dusk and sunrise, they catch dozens of birds — thrushes and not.

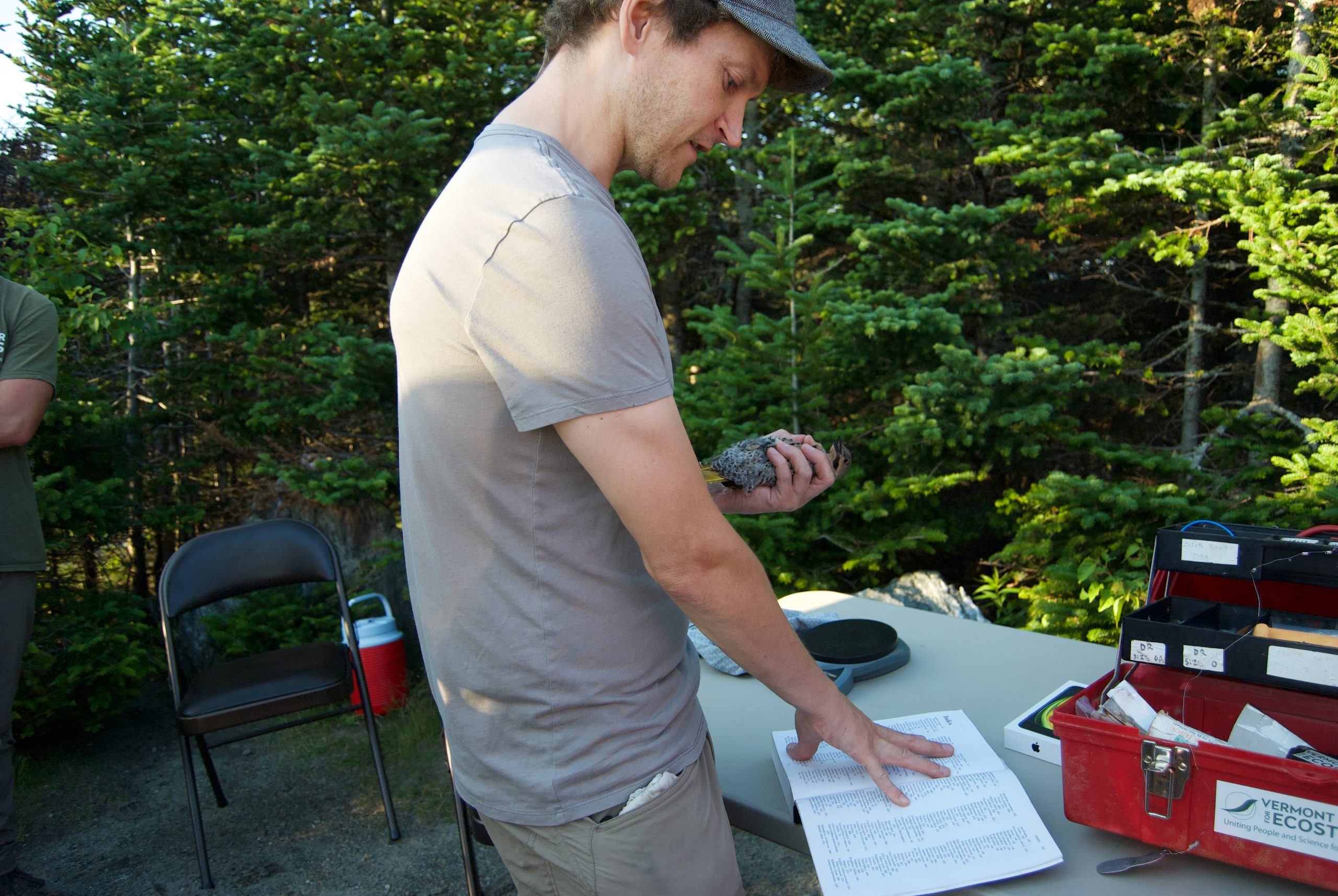

A central table, near the line of cars in which the group would sleep that night, was topped with a scale and measuring implements. The creatures waited, wiggling inside colorful cloth bags clipped to a line strung between the trees, to be measured, weighed, tagged and set free.

On this particular overnight trip, Rimmer and his colleagues did not catch a single thrush. Instead, what they found in their nests were birds that typically live at lower altitudes — oven birds, flickers, a Swainson’s thrush, a handful of warblers and others.

On a weekly blog Rimmer updates to document the long-term population study, he said the “near-total absence of local breeders other than juncos in our nets is puzzling, though not alarming.”

Rimmer said the results of this single data collection event are not necessarily meaningful. Scientists have caught plenty of Bicknell’s thrushes this summer, and the birds’ breeding season is over, so they are naturally less active.

The other birds are mostly juveniles, which typically explore new territories in late summer before they migrate. That said, anecdotally, he’s seen the beginnings of a trend.

“We are seeing greater numbers of species that are more characteristic of lower elevations, even within the mountain zone, coming up to this higher ridge line elevation,” he said. “And then we are seeing more species that don’t nest here at all that are from the hardwood forests coming up.”

The birds could be finding more or different insects that have migrated upslope, he said, but without an analysis of the data, it’s hard to tell. Rimmer said he plans to complete such an analysis of the decades of data within the next year.

“That’s why it’s so important to do long-term research like this,” he said. “From one year to the next, there’s so many things that vary.”

What’s on the way

At the least, the sampling event seemed to paint a picture of the future.

“Some of these birds that we see here, and we’re kind of surprised to find them here — you expect that’ll be a more common occurrence,” said Ryan Rebozo, the center’s director for conservation science.

Warming trends are all but sure to continue, to varying levels based on emissions reductions, according to a report issued Aug. 9 by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The report said “unless there are immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to close to 1.5°C or even 2°C will be beyond reach.”

A 2017 report from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said, as a result of climate change, “the spruce-fir habitat that currently exists as ‘islands’ of suitable habitat that support breeding Bicknell’s thrush may be substantially reduced, with the potential to be nearly eliminated, from the species’ current range in the northeastern U.S.”

Rimmer said the growth of balsam fir, which is abundant on Mansfield’s summit, is controlled by the summer temperatures. For every increase of one degree Celsius, the trees are predicted to move upslope 500 meters, he said.

“I think we’re looking at the end of the century, probably, before that becomes really pronounced,” Rimmer said.

While balsam fir may have a perilous future in Vermont, spruce trees, which may provide similar habitat, seem to be expanding, according to Anthony D’Amato, the director of the forestry program at the University of Vermont’s Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources.

D’Amato said spruce are, in fact, moving downslope. That’s a reflection of land use patterns — historically, loggers have selectively cut spruce, which was considered more valuable. Now, spruce are regenerating and taking the place of some hardwood trees that have been affected by disease.

“It’s a species that we feel, at least in parts of the Northeast, will continue to do well,” D’Amato said. “When we think about bird habitat, the importance of that conifer component in the ecosystem of maintaining that in the future is critical.”

A study he recently co-wrote about forest compositions during climate change suggests that, even as these species recover from historical harvesting practices, they may still be vulnerable.

“As the climate in the region shifts from historical norms, eastern hemlock, red spruce, and other northern temperate species (i.e. balsam fir and paper birch) show an increasing sensitivity to a warming temperatures and reduction in recruitment rates due to a suite of physiological stressors associated with a changing climate, which is consistent with previous findings,” it said.

Managing for climate change

While Rebozo said that the Vermont Center for Ecostudies is focused on data collection, rather than advocating for policy, he said there’s “room for this to be addressed” on a statewide and federal level.

“If you take a step back, and you look over the past few decades, you can see a progression in our attempt to address changes in biodiversity as a result of climate change,” he said. “But is it moving as fast and as aggressively as the issue needs? I would say no.”

Reducing emissions to slow climate change seems one of the top solutions for the thrush’s Vermont habitat, he said, but carbon sequestration efforts in forests and within farm practices, for example, could also provide some alleviation.

D’Amato has been studying new management efforts that could make forests more resilient.

“We’ve spent the last 15 years collectively understanding that climate change is happening, and these are the impacts,” D’Amato said. “I really think, at this point, we’re at a critical junction — what do we do about it?”

D’Amato and several colleagues recently used a simulation model to determine various long-term effects in three projected climate scenarios on a forest in southeastern Vermont and found that species will be affected in a variety of ways.

Trees are affected not only by temperature, but also by diseases and invasive pests, such as the emerald ash borer, whose presence is projected to climb farther north as temperatures become more amenable to them. Forest management, D’Amato said, can make an impact on the trajectory of forests and their surrounding ecosystems.

In the case of drought, D’Amato said forests that have been managed so they’re less dense seem to be more resilient and show speedier recoveries because they don’t have to compete as much to access resources.

“Do we actually try to favor tree species that are more drought tolerant?” he said. “As much as we love sugar maple and hemlock and some of those other species, they’re not the most tolerant of drought.”

Forests, D’Amato said, “might show declining vigor and declining health, but nevertheless can persist and withstand some tremendous variability.”

An indicator

Even if it takes a long time for balsam fir to disappear from the tops of these mountains, it’s “almost inconceivable” that the forthcoming changes — lower-altitude birds and species like red squirrels moving north, for example — won’t affect Bicknell’s thrush in the meantime, Rimmer said.

“We just can’t predict the exact direction those impacts will take,” he said.

Ecologically, the loss of the Bicknell’s thrush may not create a “cascading effect that affects the rest of ecology throughout Vermont,” Rimmer said.

“It is an integral part of this ecosystem,” he said. “What its role is in maintaining the balance of the different organisms here, we don’t really know. I think it’s more of a symbolic disappearance.”

Rebozo said the same changes that affect the thrush may be meaningful to many Vermonters.

“Especially in a state like Vermont — the Green Mountain State — people associate Vermont with the mountains,” he said. “Whether they never see or hear Bicnkell’s thrush, they enjoy the mountains at some level; there’s some intrinsic value there.

“It’s an indicator that it’s changing,” he said. “It’s not going to be in the future what it was in the past.”