Commodore George Dewey’s flagship, the cruiser Olympia, was in such dilapidated condition that the U.S. Navy contemplated doing what no enemy had been able to do: sink it.

The Olympia, the last remaining ship from the Spanish-American War, came out of service nearly a century ago, and for the past 64 years has been moored on the Philadelphia waterfront as part of a maritime museum.

Despite regular infusions of capital for maintenance, the ship developed serious structural issues. Consulting engineers warned that the ship could soon spring a catastrophic leak and settle to the bottom of the Delaware River.

The Navy, which a half-century ago surrendered ownership of the vessel to a nonprofit organization, suggested an alternative. It proposed either selling the ship for scrap or towing it to a spot off Cape May, New Jersey, and scuttling it to form an artificial reef.

The plan might have been a boon for aquatic life and scuba divers, but it would have been an inglorious end for Dewey’s once-famous ship.

The Olympia has been spared that fate for now, with enough money collected through private fundraising and governmental grants to stabilize the vessel. Over the next few years, the museum hopes to raise $20 million to dry-dock the Olympia so it can be taken out of the river to have its leaky keel repaired and other issues addressed.

At this point, I’m guessing that many readers are thinking, “Remind me again who George Dewey was, and what’s the big deal about his ship?”

Fair question. Don’t feel bad if you can’t place the name. Though he was one of the most famous Americans of his day, Dewey today is a forgotten hero of a forgotten war.

Dewey grew up in Montpelier and enrolled at Norwich University, back before it moved from Norwich to Northfield. But he was perhaps a little too young for Norwich, or at least school administrators thought so. They expelled him for drunkenness and for thinking it was a good idea to herd sheep into a barracks as a prank. He managed to gain admittance to the U.S. Naval Academy, from which he graduated in 1858. After graduation, he served the Navy and rose through the ranks, serving as a lieutenant under Admiral David Farragut during the Civil War.

By 1898, Dewey was made commodore of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron. With that squadron he gained international renown at the outset of the Spanish-American War, thanks to the events of May 1, 1898. Early that morning, Dewey led his squadron into Manila Bay in the Philippines. From the deck of the Olympia, Dewey commanded U.S. naval forces as they sank or captured virtually all of Spain’s Pacific fleet.

It was hardly a fair fight. The United States, at the urging of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, had been upgrading the Navy, and the Olympia was a prime example of that effort. The ship was steel-sided, one of the few naval vessels with electricity and powered steering, and was said to be the world’s second-fastest ship, able to steam at 22 knots (about 25 miles per hour).

During the six-hour battle, Dewey’s squadron overwhelmed Spain’s outdated and outgunned wooden navy. The unevenness of the clash is visible in the casualty numbers. Spain’s included 167 dead and 214 wounded. Aboard Dewey’s fleet, no one was killed in the fighting and only eight were wounded. One American sailor did die that day, but it was from heat stroke.

This was no ordinary battle that Dewey won. This one effectively started and ended the Spanish-American War in the Pacific — fighting in Cuba would erupt and end that summer.

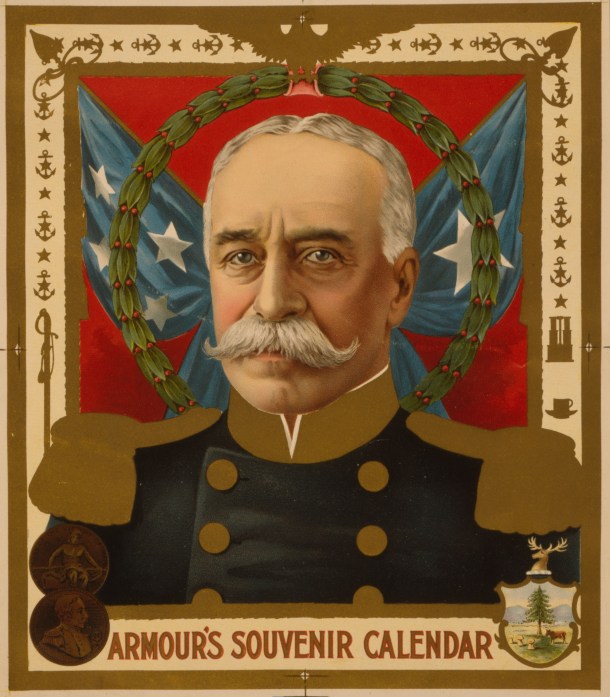

Across the United States, people wrote songs in Dewey’s honor, the masses purchased souvenir dinner plates bearing his image, and countless parents named baby boys after him. At one point, admirers even pushed him to run for president.

Dewey didn’t mind the prodding but soon showed he was ill suited for politics, once mentioning that he had never voted in a presidential election and suggesting that he thought the president’s job was merely to execute the will of Congress, rather than lead a separate branch of government.

Soon after the fighting stopped, American Secretary of State John Hay dubbed it a “splendid little war.” Two years later, it seemed like anything but. When Americans refused to cede control of the Philippines to the rebels who had been fighting the Spanish, the rebels launched an armed insurgency that killed more than 4,000 American troops and an estimated 20,000 Filipinos.

In 1902, a Senate panel grilled Dewey over what had gone wrong. Some people believed that the uprising had been triggered when he allegedly promised the rebels independence in exchange for their help fighting the Spanish. But Dewey’s reputation survived the inquiry, and in 1903 he was promoted to the newly created rank of admiral of the Navy, the Navy’s highest position. Dewey remains the only person to attain that rank.

The war is often overlooked today, despite its repercussions. The conflict marked the emergence of the United States on the world stage and launched what historians call the American Century. Depending on your perspective, the American Century was either an era of great advancement, with the United States bringing the gift of democracy to the four corners of the Earth, or a time of venal imperialism, in which the United States took the riches of the rest of the world. Or perhaps a bit of both.

Whatever it was, the century was unquestionably world changing. And Dewey and the Olympia were there at its inception.

Built in 1895, the Olympia remained in service long after Dewey commanded it. The vessel transported troops during World War I. And a century ago this fall, the Olympia was given the honor of transporting that war’s Unknown Soldier from France to the United States for burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

The Olympia almost didn’t complete that final mission. As it sailed across the Atlantic with the casket of the soldier lashed to the deck, the Olympia had to fight for 10 days through tropical storms that produced 20- to 30-foot waves. Fearing the ship might sink, the captain asked the chaplain to assemble the men who were off duty to pray for the vessel’s survival. To mark the centennial of that little-known story, the Independence Seaport Museum is presenting a new exhibit from now until Thanksgiving.

The Olympia managed to reach the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C., without loss of life on Nov. 9, 1921. Members of the military and some dignitaries greeted the vessel ceremoniously.

George Dewey was not among them. He was already at Arlington. The man who had commanded the Olympia during its first historic mission had died three years earlier at his Washington home and been buried at the national military cemetery.

Correction: The original version of this article erroneously stated Dewey had graduated from Norwich.