Hundreds of Vermonters have been barred from receiving new deliveries of home heating oil until technicians repair or replace their faulty fuel-oil tanks.

With winter approaching, those homeowners are worried about whether they’ll be able to heat their homes.

At the same time, fuel companies are hustling to fix the problems before deep winter arrives.

“We are extremely busy,” said Conrad Bellavance, safety and compliance manager at Fred’s Energy, which serves several counties in northern Vermont. Even so, he said, “we’re scheduling installs for tanks into early December.”

In 2017, Vermont adopted a law requiring all homeowners with above-ground storage tanks for heating oil to schedule an inspection before Aug. 15, 2020. “Above-ground” includes locations in the basements of homes and businesses, and that’s where the vast majority of above-ground tanks are located.

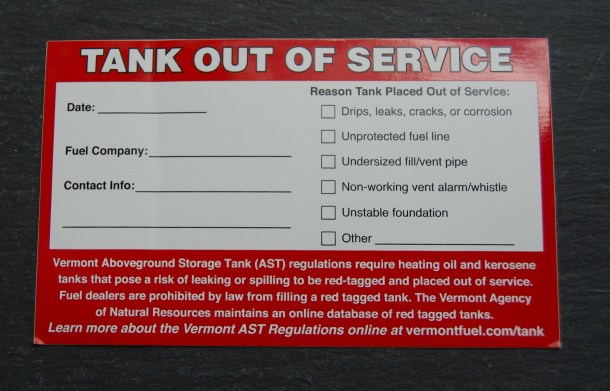

Technicians are required to affix red tags to any tanks ruled “at imminent risk” of spilling. The tags tell distributors not to fill the tanks, and any distributor who fills a red-tagged tank could be held liable for the cleanup costs if the fuel oil spills. Those spills can turn into an expensive environmental nightmare if the fuel oil gets into underground water.

More than 650 Vermonters’ tanks have been red-tagged since Aug. 1 and are still awaiting repair or replacement, according to a public list updated daily by the Waste Management and Prevention Division of the Department of Environmental Conservation. On Tuesday alone, the state added nine fuel tanks to the list.

The list, which dates back to 2017, includes more than 1,600 people whose tanks have been red-tagged, though some may have switched to alternative heating systems.

When the law was adopted, inspecting the state’s 110,000 above-ground fuel-oil tanks within three years looked like a “mammoth task,” but one that could be accomplished, said Matt Cota, executive director of the Vermont Fuel Dealers Association. And, the inspection program has worked. Cota said strict inspection regulations have led to significantly fewer spills.

But by this spring, many tanks still hadn’t been inspected, and then the pandemic arrived, effectively halting inspections for several months. While technicians continued to inspect outdoor tanks, Cota said the vast majority are located in homeowners’ basements.

“Based on the surveys that we have done with our member companies, I would say that about 80,000 or more tanks have been inspected in the last three years,” Cota said. “But there’s still a significant number of tanks that have not been inspected.”

Rushing to inspect 30,000 tanks

Technicians have been rushing to inspect the roughly 30,000 remaining tanks, and those that don’t meet five safety criteria are red-tagged. Many customers have waited more than a month for technicians to repair or replace tagged tanks.

Several other factors have affected the situation, Cota said: The industry has been losing its workforce as older technicians retire, and Vermont has had a construction boom as remote workers flock to the state. Some have requested upgrades to heating systems in summer homes that will be occupied over the winter, for example.

Others couldn’t afford new fuel tanks, which cost between $1,800 and $2,400, and held off on replacements.

Knowing technicians couldn’t make the Aug. 15 deadline, the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation worked with the Vermont Fuel Dealers Association to extend it until the end of November. Then, with the backlog still a big problem, the state extended the inspection deadline last week until May 1.

Fuel companies have to inspect tanks before filling them. Technicians typically don’t risk a spill, and Cota said strict inspection regulations have led to significantly fewer spills.

As technicians work on the backlog, fuel companies say they’re busier than they’ve ever been, and customers say they’re worried about being able to heat their homes.

“That’s why I think we’re in a panic — well, not a panic,” Cota said. “I would say we’re carefully coordinating how we get to the remaining tanks before the winter really starts to get into gear.”

Cold weather coming fast

Jennifer Endicott and her husband own the Taftsville Country Store. The building also houses the post office; upstairs, a family with young children rents an apartment.

Endicott thought her fuel-tank inspections were up to date, but then she received a letter from her fuel distributor, indicating her fuel tank needed to be checked. She scheduled the inspection, and when a technician arrived, he red-tagged the tank, saying it was beyond repair and needed to be replaced.

The tank was empty, and it is the only source of heat for the building. Knowing the red tag would prevent anyone from delivering fuel, she worried for the family upstairs, and for the postal workers.

“I immediately contacted (the company) to say, how could you, in good conscience, do an inspection right before cold weather is coming, tell us a tank needs to be replaced, and you can’t even give us a timeframe for when you could do that work?” she said.

The fuel dealer referred Endicott to the state, where she spoke with a representative from the state’s Waste Management and Prevention Division who listed several contingency plans for situations like hers. The company could deliver small amounts of fuel, he said, or it could install a small oil drum to last until the tank could be replaced. According to Endicott, the fuel company said it hadn’t received that guidance from the state.

From there, she called several state representatives and even sent a letter to Gov. Phil Scott. No one could find a resolution.

Finally, through a connection with the upstairs tenants, the district manager of another fuel company visited the building and inspected the tank. He disagreed with the technician who had red-tagged Endicott’s fuel tank, finding that it did not pose an imminent risk of leaking. He removed the red tag, and the state approved his decision.

“That’s all well and good; my husband and I are fine now. We can get whatever we need to get done over time,” Endicott said. “But what about all these other people that nobody is speaking for?”

Replacing fuel tanks, one by one

Scott Sullivan, owner of Rutland Fuel Co., said his days have been dominated recently by tank work. A collection of failed fuel-oil tanks sits at the back of the company’s property, and Sullivan said Rutland Fuel has collected more than five times the number of tanks it would in a typical season.

He attributes the increase in tank work partly to stricter regulations. The size of fill pipes and vent pipes, which distributors use to fill the tanks, must now have a minimum diameter of 1.25 inches, for example.

“Tanks might be functioning perfectly well, but if the vent is too small, now, that’s a red-taggable offense,” he said.

Sullivan’s workforce has stayed the same, but he could use more workers as the demand ramps up.

“I’m getting an incredible amount of work with my same number of staff,” he said. “It’s been quite a challenge. My service guys have been working five or six days a week, almost exclusively on tanks.”

Sullivan would normally have his staff cleaning furnaces — sometimes eight in a day — but that work has taken a back seat to tank inspections, repairs and replacements. A new requirement mandates that above-ground tanks must sit on stable surfaces, which sometimes means pouring a concrete pad on which the new tank will sit. Technicians must return to homes several times to complete those jobs.

Calls are coming from longtime customers, but also from new customers who have inquired about inspections ahead of the deadline.

“It’s just been an incredible amount of work,” Sullivan said. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

In northern Vermont, Fred’s Energy is trying to ensure that customers have heat, but also can’t “look the other way” when it comes to red-tagging tanks, Bellavance said. The company has red-tagged dozens of tanks since Aug. 1.

Bellavance said he’s as concerned as his customers, but feels his hands are tied — the only option is to keep plugging along, replacing the tanks one by one.

“We can set up a temporary tank; there are things we can do,” he said. “The problem is, there are so many, if we take time now to do something, it just delays somebody else’s tank later on, down the road.”

Contingency plans

When Jennifer Endicott called the state, she reached Marc Roy, section chief of Vermont’s Hazardous Waste Management Program.

Roy said he’s been a busy guy.

“I think, if you looked at the numbers and dumped them onto a spreadsheet, (inspections) steadily ramp up all the way into last month, and they’re perhaps starting to trail off in October as the deadline got kicked out and the concentration has been on upgrades and repairs,” he said.

People with an empty, red-tagged tank can hand-fill oil into their tanks in emergencies, Roy said. He also said fuel companies can, on a case-by-case basis, fill red-tagged tanks if they think the tanks can hold the fuel through the winter — though fuel companies might hesitate, afraid of being liable if the tank leaks. Companies can also deliver small drums of heating oil, though he isn’t sure how often those solutions are being employed.

Roy said the regulations are necessary for environmental and human health, and fuel companies and homeowners have had three years to have their tanks inspected.

“Once we get the whole universe kind of up to speed going forward, it should really keep things down to a minimum,” Roy said.

Endicott wishes that, in the pandemic, the state would suspend regulations that lead to red tags.

“This is insane. This is happening because of regulations you control,” she said, referring to legislators and the Scott administration. “You can allow those regulations to suspend during a pandemic. You’ve already done that. Why wouldn’t you do it now? Why would you force families and businesses to be in this situation with no heat?”

Several community action organizations have been thinking about this issue for months, particularly as it relates to low-income Vermonters. People who qualify can apply for seasonal fuel programs and grants that cover the cost of installing a new tank.

“If you qualify with us, there is no out-of-pocket cost for the homeowner,” said Mark Therrien, weatherization program manager at BROC, a community action organization in Bennington and Rutland counties.

Community action agencies can also call on fuel companies to make emergency fuel deliveries to people with no heat or unsafe heat situations. Therrien hopes low-income Vermonters know the assistance is available, and said his organization tries hard to spread the word.

“If you’re without heat, or at risk of being without heat, if you do have a red-tagged tank, call a local community action agency to see if you qualify,” he said. There are five such agencies in Vermont: BROC — Community Action in Southwestern Vermont, covering Bennington and Rutland counties, 800-717-2762; Capstone Community Action, in Washington, Lamoille and Orange counties, 800-639-1053; Champlain Valley Office of Economic Opportunity, in Chittenden, Addison, Franklin and Grand Isle counties, 802-862-2771; Northeast Kingdom Community Action, in Caledonia, Essex and Orleans counties, 802-334-7316; and Southeastern Vermont Community Action, in Windham and Windsor counties, 800-464-9951.