Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

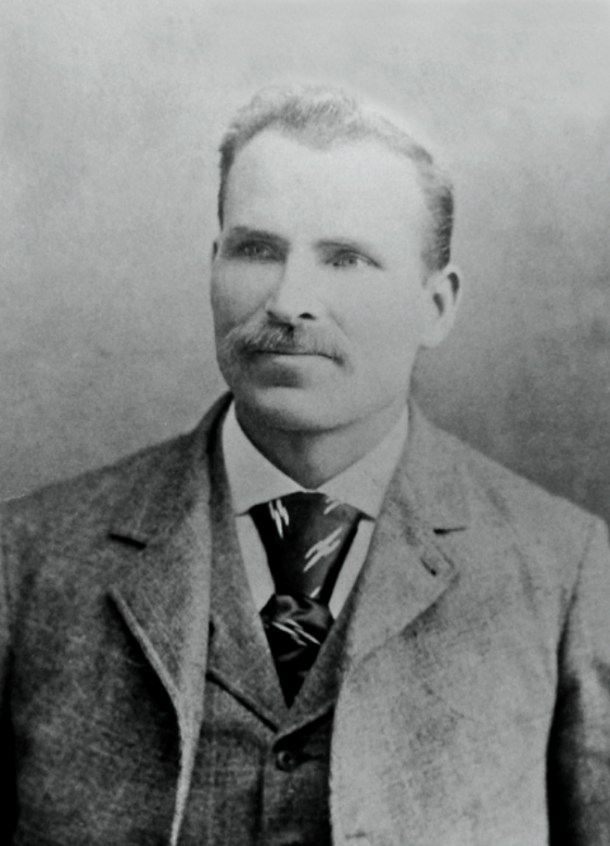

Vermont’s first socialist mayor wasn’t known for his unruly white hair or his Brooklyn accent. He kept his hair short and his mustache neatly trimmed, and if he had a discernible accent, it was a remnant of the brogue he picked up during his childhood in Scotland.

Like Bernie Sanders, Robert Gordon wasn’t what the establishment was looking for in a mayor. Business and community leaders were interested in maintaining the status quo, but Gordon saw changes that needed to be made in his adopted home of Barre.

By the time Gordon ran for mayor in 1916, Barre had experienced decades of dramatic change. In 1870, Barre had been an unremarkable Vermont town with a population of roughly 1,900. But after the Central Vermont Railroad built a spur to access the local granite quarries, Barre’s population soared. By 1910, Barre had been divided into a city and town with nearly 15,000 residents combined, more than two-thirds of whom lived in the city. The newcomers were mainly immigrants. They came from all over: Russia, Ireland, Finland, Greece, France, Sweden, and French-speaking parts of Canada. But the dominant ethnic groups were the Italians and the Scots. Gordon was a Scot who arrived in Barre in 1880 at the age of 15 to work as a stonecutter.

During the early years of the 1900s, the city was known as a “hotbed of radicalism,” according to historian Robert Weir, who wrote about socialism in Barre in Vermont History, the journal of the Vermont Historical Society. Barre’s reputation was well deserved. In 1900, Italian anarchists caused a violent disruption at the city’s Socialist Labor Party Hall. After the police broke up the fight, Barre’s police chief, Patrick Brown, was shot three times by an anarchist as he walked back to the station. Doctors were pessimistic about Brown’s chances of surviving, but the chief recovered. Three years later, during another dispute between anarchists and socialists at the labor hall, an anarchist accidentally shot and killed an innocent bystander, a well-respected stone carver named Elia Corti.

The city was also home to Luigi Galleani, an internationally known anarchist, who published the Italian-language Cronaca Sovversiva (Subversive Chronicle). In addition to local rabble-rousers, Barre also regularly received visits from leading anarchist, socialist and labor leaders, including Emma Goldman, Eugene Debs and Bill Haywood.

Unions held great power in the city. At the time, no more than 7% of American workers were unionized, but in Barre almost 90% were. Major labor strikes occurred regularly. Workers’ grievances were understandable: Their hours were long, their work grueling and dangerous. Breathing in granite dust caused many workers to suffer from silicosis and tuberculosis, both lung ailments. While life expectancy nationally for men was about 50 in 1900, in Barre it was barely 42.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, supporters of anarchists and socialists in Barre outnumbered backers of the Democrats and Republicans. So to ensure that power remained in their hands, each year the Republicans and Democrats joined forces to hold a Citizens Caucus several weeks before Town Meeting Day, the first Tuesday in March. The caucus served as a sort of primary, with the winner being nominated not as the Republican or Democratic candidate, but as the Citizens Caucus candidate. Advocates of the caucus claimed its purpose was to ensure that on election day, voters didn’t just choose candidates based on party labels; in reality, according to historian Paul Demers, the caucus made sure that the “right people,” the candidates supported by the political and business elite, won the election. The Barre Daily Times invariably endorsed Citizens Caucus winners, giving them an added boost, and the caucus winners almost always won election.

The two socialist parties — the fiery Socialist Labor Party and the more mainstream Socialist Party of America — didn’t help their chances by constantly fighting each other for support from the community’s left-wing voters.

In 1916, it seemed that the election was in the bag for the Citizens Caucus candidate, as usual. On a February evening, roughly 200 voters, or 10% of registered voters, assembled at the Barre Opera House to nominate the caucus’ slate of candidates. The sitting mayor, Frank Langley, who was also editor of the Barre Daily Times, ran unopposed. He was clearly the establishment’s pick. The Daily Times seemed to foresee an uneventful election in March when it commented on the “element of apathy that has settled down over the political situation in Barre to date.”

But during the run-up to the March election in 1916, Gordon, as the Socialist Party candidate, astutely appealed to the interests of the city’s large community of laborers by positioning himself as the moderate alternative to the Socialist Labor Party candidate.

Contrary to the Daily Times’ prediction, the mayoral election drew great interest. Nearly 83% of the city’s 2,060 registered voters cast ballots, and Gordon won comfortably.

For an upstart candidate, Gordon worked surprisingly smoothly with the city’s aldermen, who approved 23 of his 24 appointments to his administration. The only one rejected was Fred Suitor, who would learn from Gordon’s tactics and tenure in office and become Barre’s second socialist mayor 13 years later.

Gordon’s approach as mayor was more evolutionary than revolutionary, Weir notes. He was more practical than ideological. He wanted to use the power of government, which he saw as people working together toward a common goal, to resolve issues facing the city.

Gordon and other socialists — Americans elected 1,200 to city offices between 1912 and 1919 — took a different approach from the era’s other reform movement of the period, the Progressives. Whereas Progressive politicians relied on a top-down system of having “experts” provide answers for how government should act, Gordon and other socialists looked to the people to help provide guidance. Though Vermont didn’t yet have laws requiring open governmental meetings, Gordon invited the public in to raise concerns and offer suggestions.

The issues he faced during his one term in office were of the mundane sort faced by every mayor. Gordon was alarmed that the city’s capital projects fund was unsecured — if the large bank holding the money failed, the money would be lost. He successfully fought to move the funds to three other banks and secured bonds to protect the money.

To address citizens’ complaints, his administration arranged for 35 miles of new water lines to be laid, installed improved lighting at Depot Square, purchased a new truck for the city street department, and built a Civil War monument. The most typically socialistic change Gordon made was creating a municipal service to purchase and distribute coal in the city.

Gordon had loftier goals he was unable to accomplish during his brief tenure: He wanted to institute an eight-hour workday for city workers, restructure the tax code to discourage speculation, provide free medical care, offer free evening educational classes, and create a city-owned hospital and sanitarium, which would treat the many cases of tuberculosis suffered by granite workers.

Still, he had proved highly competent at achieving day-to-day tasks at which his predecessors had failed. Gordon left office at the age of 52, which counted as old for a stonecutter in Barre. He soon left Barre too. He moved to Lynn, Massachusetts, where he sought treatment at a tuberculosis hospital, like the one he had hoped to building in Vermont. He died there at the age of 56.