BRATTLEBORO — First came the local cruisers, then the state police running with rifles, then a U.S. attorney’s press release detailing the Feb. 28 dawn raid on a headline-grabbing drug house between a special needs school and a residence for single mothers and children.

Neighbors shoveling the previous night’s snow watched as authorities seized narcotics and arms from an apartment at 33 Oak St. exactly two months after they first did. This time, they arrested all the occupants and placed them in federal custody, ending a year of cocaine, heroin and fentanyl dealing and related crime shaded by the block’s stately trees.

End of story?

“I wish,” Brattleboro Police Chief Michael Fitzgerald says.

Talk to townspeople and they’ll tell you about strangers gravitating to other streets, stealing from downtown tip jars or using drugs in public restrooms — so much so, a rising number of businesses have obtained no-trespass orders against offenders while the local library now stocks Narcan nasal spray to help reverse opioid overdoses.

“Closing down one place,” Fitzgerald says, “does not solve the problem.”

This southeastern Vermont town is one of many in the state wrestling with how to fight not only addiction but also such aggravators as poverty and mental illness.

“I’ve heard more times than not from educated people, ‘Why don’t they just stop?’” Fitzgerald says. “People don’t understand the true depth of this.”

For neighbors of the recently raided drug house, the battle hits home in other ways. They pushed the landlord to evict dealers squatting at another 33 Oak St. apartment last summer, only to watch sales move to a different unit of the same building. They’re now asking why the government can’t take the property through civil forfeiture, why there’s less than full disclosure about a former occupant who has moved from federal custody to an addiction treatment center, and why that defendant could ask to await trial at an address known for a reported drug-related assault last year.

“We have to be vigilant,” says one neighbor, scared to be named yet seeking more facts. “So I don’t understand — you’re putting someone back in the environment that got them in trouble in the first place?”

‘There’s a lot more behind the scenes’

For all of 33 Oak St.’s unique specifics — few drug houses are adjacent not only to a school and a residence for single mothers but also two investment properties owned by a former governor, Peter Shumlin, who dedicated an entire State-of-the-State address to opioid abuse — authorities say the situation is a good example of the challenges they face throughout Vermont before and after closure.

“The work doesn’t end with a raid,” says Sgt. Chris Lora of the State Police Drug Task Force. “There’s a lot more behind the scenes the public doesn’t hear about or see.”

Neighbors who watched local cruisers descend at 6 a.m. Feb. 28, for example, didn’t realize the seeming blue-collar workers parking their well-worn SUVs along the street weren’t in the wrong place at the wrong time but instead undercover officers who had scoped out the house for weeks.

As the press had reported local frustration about seeming inaction over suspicious activity, plainclothes police had worked secretly with confidential informants to record drug sales in order to obtain a search warrant and court evidence.

They started Feb. 15 by purchasing $90 of heroin, court records show. Feb. 20, a day after cruisers temporarily closed the street upon reports of gunfire, they bought $160 more. Feb. 22, as headlines revealed the arrest of former apartment dweller and alleged dealer Chyquan Cupe, they bought $160 more. And Feb. 25, as Cupe awaited a federal detention hearing, they bought $200 more.

At dawn Feb. 28, police stormed the apartment, arrested tenant Francis Macie and fellow apartment dwellers Juan A. Sanchez Jr., Linda Wainwright and Desiree Wells-Cooper, and seized suspected narcotics and cocaine base, two digital scales, intravenous drug needles and a pistol with a full magazine of bullets.

“It was what we expected,” Lora says today. “We accomplished what we wanted.”

Neighbors, for their part, welcomed the fact that authorities sought to hold all five occupants in federal custody after each pleaded not guilty in U.S. District Court in Burlington. They’ve seen too many others arrested for drug crimes rack up more of a record after they were released while awaiting trial.

‘The cops can’t catch me — they’re stupid’

Cupe is a prime example. He’s been arrested at least four times in the past two years but keeps fleeing after being charged and released. None of his cases yet have reached trial.

When the now 21-year-old faced his first Vermont charges last year, his lawyer asked a judge to lower the accused’s $25,000 bail bond for alleged assault and burglary, arguing the defendant had just moved to Oak Street, a middle-class address not associated with criminal conduct.

The lawyer didn’t mention Cupe already had a $250,000 bond against him in his home state of Connecticut after police found him during a 2017 Hartford drug raid with a loaded .40 caliber pistol.

Cupe was released in both instances to await trial, only to be stopped by Brattleboro police last October for new charges of possession of cocaine, resisting arrest and attempting to escape — the latter while handcuffed. Yet Cupe was free again this past Christmas when he allegedly held two women at gunpoint at 33 Oak St. and forced them to brawl over a $200 drug debt, then reportedly pulled one by the hair two days later to announce “I’m going to beat and kill you right here.”

When police arrived with a search warrant Dec. 28, they seized an unspecified “large amount” of drugs, a handgun with an obliterated serial number and a sawed-off 12-gauge shotgun — both weapons loaded and “strategically located” under sofa cushions and a pile of clothes.

Cupe, however, wasn’t there. Authorities, publicizing the fact he was “armed and dangerous and should not be approached by members of the public,” later arrested him on Feb. 7 after he had posted numerous messages on Facebook.

He wrote Jan. 30: “Who wanna chill before I’m locked up?”

And Feb. 6: “I think ima (sic) post a video of me and everyone I love before I go in.”

At a federal detention hearing, the federal prosecutor played a nearly eight-minute Facebook Live video Cupe had posted in which he waved what looked like a pistol while spouting a curse-laden monologue targeting authorities.

“The cops can’t catch me — they’re stupid,” Cupe said.

In response, Cupe’s federal public defender argued his client shouldn’t be detained because he lacked prior convictions (he didn’t explain Cupe has a slew of felony and misdemeanor charges pending) and the video didn’t prove the item he was holding was a gun (neglecting to note his 2017 Connecticut arrest for carrying a loaded pistol or the December seizure of two weapons from his residence).

At a subsequent hearing on state charges, a Windham County judge asked if Cupe was absent because he was in federal custody. The accused’s local lawyer replied the defendant was “in state” and kept repeating that until the judge noted the dodge — Cupe was in federal custody that day at the Northwest State Correctional Facility in Swanton — was an unwelcome game of semantics.

‘Long term you have to address it or else …’

The Vermont U.S. Attorney’s Office has publicized the Brattleboro drug house arrests in a press release that was the top story in a recent U.S. Justice Department national newsletter. Neighbors, however, are asking why related court records aren’t always as forthcoming.

Federal officials won’t say why they took over the case from local and state authorities, although they stress it wasn’t for publicity.

“We are in the business of prosecuting drug dealers and traffickers,” U.S. Attorney’s Office spokesperson Kraig LaPorte says, “and we have partnerships with agencies throughout Vermont. Brattleboro is as important to us as Bennington, Newport and Derby, St. Albans and every location in between.”

Neighbors are attempting to take advantage of the federal intervention. They learned the government seized three adjacent Rutland drug houses through civil forfeiture in 2016 and turned them over to a nonprofit outfit that works on affordable housing and community redevelopment. Brattleboro residents have inquired about the possibility of doing the same at 33 Oak St.

“Our office does do the process,” LaPorte says in response, “but I can’t speak specifically on any case.”

Officials are talking more about preparing to prosecute the five defendants, all who were imprisoned immediately under federal guidelines rather than set free on bail as is common practice locally.

“We don’t look at taking cases based on whether we can have someone detained,” LaPorte says, “although there is an advantage from a public safety standpoint.”

Recently Macie, the tenant on the lease of the raided 33 Oak St. apartment, has received court permission to move from federal custody to the Valley Vista addiction treatment center in Bradford, after which time he has sought to await trial at a friend’s apartment back in Brattleboro.

Neighbors have questioned whether tax dollars are paying for the treatment, whose average length is about a month and costs as much as $25,000, according to the website addictionresource.com.

The U.S. attorney’s office says that’s a good question, but one for the U.S. Marshals Service that detains defendants. The U.S. Marshals Service, in turn, says that’s a good question, too, but responds that it no longer holds Macie and therefore no longer is responsible for him.

Valley Vista, for its part, didn’t answer calls for comment.

Enter the U.S. Probation Office in Burlington, which reports it covers the costs of treatment if a defendant doesn’t have some sort of public or private health insurance plan. Joseph McNamara, chief U.S. probation officer for Vermont, knows some taxpayers may question why they should pay the bill. But he notes the government is picking up the tab whatever happens and treatment often costs less.

“Incarceration is ridiculously expensive,” McNamara says. “If someone stays in U.S. Marshals’ custody, it’s way more per day.”

Officials can’t offer specific cost-comparison numbers in this case, but point to studies that show rehabilitation can lower both short- and long-term expenses.

“Drug abuse treatment is cost effective in reducing drug use and bringing about related savings,” the National Institute on Drug Abuse concluded in a recent report. “The largest economic benefit of treatment is seen in avoided costs of crime (incarceration and victimization costs).”

One goal of treatment, McNamara says, is to stop addiction that seeds crime.

“By just locking someone up, we’ve delayed fixing the problem,” he says. “Long term you have to address it or else it’s going to be a revolving door. We’re aiming to do more than solve someone’s substance use disorder but also the criminal activity that goes with it.”

‘People have to ask … what’s the underlying issue?’

Neighbors also are concerned that Macie has asked in court papers to stay after treatment at a School Street apartment owned by the same landlord as 33 Oak St. (Robert Remy-Powers, who hasn’t spoken on the record to the press since the raid and wants to be quoted only without being named) and where Cupe was charged with assaulting an occupant in May 2018.

A resulting order setting conditions of release approved treatment but doesn’t spell out a decision on the School Street apartment transfer. Asked to elaborate on questions not answered in court papers, federal officials usually say they can speak generally but not about specifics.

“Unfortunately, some of the process we can’t talk about,” LaPorte says.

But pressed in this instance, they revealed prosecutors opposed the Macie request and his lawyer had withdrawn it.

“In most cases if not all, we usually check out the residence because we don’t want to wipe out the progress that has been made in treatment,” McNamara says. “We’re trying to remove all the factors that might lead to a relapse.”

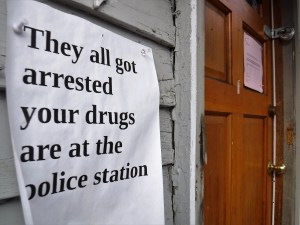

Back at 33 Oak St., life is quiet after more than 80 police calls this past year for reports ranging from loitering, noise and disorderly conduct to overdoses, assaults and stolen vehicles, workmen have painted over “we sell drugs” graffiti on the house, while fewer out-of-state vehicles are pulling up as people discover the apartment they’re aiming to visit is vacant.

Dealing, however, hasn’t stopped — just shifted to other parts of town.

“What we’re competing against is money,” Fitzgerald says at the Brattleboro Police Department. “People can make more in a day than you or I do in a month.”

Three weeks after the 33 Oak St. raid, authorities seized two more alleged dealers, crack cocaine and an unspecified “large amount” of cash from a Canal Street apartment next to a vacant pizza parlor.

“The problem is definitely getting more publicity,” Fitzgerald says, “but it has always been there. People are just seeing it more. By slowly hitting these houses, we’re disrupting things.”

Yet the answer, the police chief adds, isn’t as simple as increasing arrests.

“Law enforcement is part of the solution, but you can’t dump all this on us,” Fitzgerald says. “A dealer finds someone who’s vulnerable, takes over their apartment and exploits them. What people have to ask is, what’s the underlying issue? Is it housing, employment, mental health?”

Until then, authorities will try to keep up.

“Our investigations do take time, but we’re already making moves for the next place,” Lora says at the State Police Drug Task Force. “I think every arrest is beneficial, whether it’s quality of life for residents of a neighborhood or the thing we can’t quantify: Did we save someone’s life because they couldn’t get drugs? We don’t want dealers to be comfortable. The next knock on the door might be us.”