Stress on resources limits community mental health treatment services for offenders

Read more in this series

‘We just don’t have the people’

‘This is bankrupting our state’

Prison, a tough environment for mentally ill

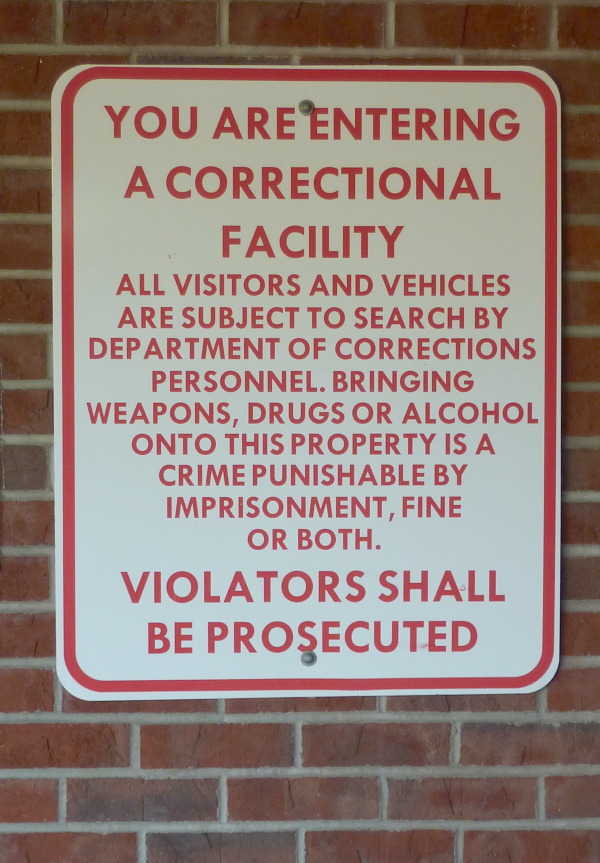

Many of Vermont’s prisoners have been diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, and the majority of them are eventually released into the community. But they often fail to receive the support in the community that they need to keep from reoffending, a legislative committee found. Consequently, many end up back in prison where treatment services for people with mental illness are limited.

For the individual who is punished as a consequence of not receiving the structure, supervision and mental health care he needs to stay out of jail, this cycle represents a cruel Catch-22. For the taxpayers who fund the various parts of the cycle, it represents a costly and wasteful systems failure.

Advocates for people with mental illness charge that recent budget cuts have strained local agencies’ ability to provide services, and they anticipate that as a result more former prisoners with mental illnesses will end up back in prison.

That’s because reintegrating prisoners with mental illnesses into their communities depends on the capacity of local mental health agencies to deliver well-coordinated, comprehensive services. Whether these organizations have the required capacity is an open question.

“Many communities have not been given the resources that will enable them to provide the services needed,” said the Joint Legislative Corrections Oversight Committee in its 2008 report. Sometimes services to newly released prisoners aren’t provided promptly, according to the report. Sometimes they aren’t comprehensive enough. “Even the courts that are aware that many mentally ill offenders could be better served in the community are frustrated at the lack of community services available,” the committee said.

The report also cited wide discrepancies in the quality of services: Some communities “do not provide the needed services, some are reluctant to provide services to a person who may be violent, and some do not have the capacity to take on new patients and therefore have long waiting lists. A lack of community services means that more mentally ill people are likely to be placed in the prisons,” the committee wrote.

Budget cuts haven’t helped

Some advocates maintain that cuts in community mental health centers’ staff and budgets have left the agencies ill-equipped to maintain their earlier level of services, let alone provide more care.

Michael Hartman, Commissioner of the Department of Mental Health, acknowledges that the budget reductions have had some impact on the agencies but maintains that so far the cuts have affected the staff more than services.

Mental health, substance abuse and developmental disabilities services are provided by “designated agencies,” that is, private, nonprofit organizations around the state, funded primarily by the Department of Mental Health. This year, state budget cuts led to a 6 percent staff reduction at the designated agencies.

The 2009 budget reductions eliminated 178 of more than 3,600 full-time-equivalents who were employed in the designated agencies in November 2008, said Julie Tessler, executive director of the Vermont Council of Developmental and Mental Health Services. (Hartman noted that more than 300 people were laid off at the Agency of Human Services, which had some 3,000 employees.)

How dire were the agencies’ budget cuts? It depends on your point of view.

The issue topped the 2009 advocacy agenda of the National Alliance on Mental Illness-Vermont, which states “given current demands and cost pressures, these agencies need a minimum 8.5% annual increase over 2008 state general fund budget just to keep pace with their current caseload … Further state cuts are likely to wreak havoc in the ability of these agencies’ staff to support individuals in recovery.”

Funding to the designated agencies was reduced by about 3.75 percent this year, Hartman said, but he noted that the reduction came after three consecutive years of 7 percent increases: “Because of that, there was some ability to absorb a 3 percent decrease.” He said that a number of the designated agencies were able to restore some of the positions they had cut, and three of the 10 agencies proposed salary increases for their staffs.

“We fund per capita mental health services at a higher rate than almost any other state in the country,” Hartman said. “We’re always in the top 10 – sometimes in the top five. We have a very high penetration rate of services to severely mentally ill adults, and the second highest in the country to children. We are funding the best we can with what we have to work with.”

Increased demand stresses system

Nevertheless, he acknowledged that there’s a limit to the agencies’ ability to absorb cuts.

“I don’t want to give the image that everything’s hunky-dory, that everybody’s fine. I think the reality of it is that, like other parts of the country, we’re seeing more people come in the door looking for services and we have less staff able to provide those services.”

The increased demand, he said, is coming from “the person on the street who has lost their job, their housing is unstable and they’ve maybe always had some mental health issues but could hold them together as long as everything else is okay. Now everything else is not okay.”

Tessler disputes Hartman’s claim that the designated agencies have not reduced services, and she offers a dark view of the effects she foresees ultimately rippling out to the criminal justice system.

Tessler notes that eligibility guidelines have been tightened, so some clients no longer qualify for services. Clients who do qualify get fewer hours of therapy or receive group therapy instead of individualized therapy. There are fewer staff members to help people find jobs and support them in carrying out job responsibilities. (“Nothing is as therapeutic as work,” Tessler observed.) And with fewer resources, it’s harder for the agencies to provide psychiatric assessment and treatment.

“Every time we provide those services, we lose money because the state reimburses us at such a low rate,” Tessler declared. “That can also affect (psychiatric) medications and medication management.” If a medication doesn’t work or there are side effects or a dose needs adjusting, patients need to be able to get in touch with their providers easily. “It’s so critical,” Tessler stressed.

As a result of the reduction in access to mental health care, more people are showing up in emergency rooms, Tessler said. She added, “The census at the Vermont State Hospital has been quite high all summer.” She attributes this to people of modest means not seeking help until their symptoms become acute.

Based on what she is seeing, Tessler says, “We do believe that more people will end up with interventions from police and public safety, and more people will end up in correctional facilities.”

Systems failure?

Elaine Alfano, deputy policy director of the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law and a former state representative for Calais, argues that the heightened risk of Vermonters with mental illness for involvement with the criminal justice system represents a systems failure. (Alfano served for six years on the House Health and Welfare Committee.)

“Accepting such scenarios without seeing them as system failures that urgently need to be addressed continues a pattern of unacceptable consequences, belying the availability of effective mental health treatment and community supports that allow people with serious mental illness to lead stable and productive lives in the community,” she said in an e-mail.

“While Vermont has a tradition of good laws and policies, it has trouble … with implementation and sustaining promising programs. Translating polices into effective practices takes strong leadership, on-going use of science about what works, organizational behavior and performance improvement, accountability and a thoughtful approach to systematization,” she wrote.

Alfaro sees adopting performance improvement programs as a way to ensure that policies get implemented.

“Performance improvement programs are ubiquitous in business and in health care,” she noted, “and there is growing recognition that these efforts should be applied to whole systems and governmental endeavors.”