Prison population growth tied to recidivism, mental illness

Half of Vermont’s prison inmates released in 2004 had new convictions within three years, according to the Department of Corrections.

Vermont doesn’t track recidivism by prisoners’ mental health status, but a 1999 report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics indicates that the national rate is even higher among prisoners with mental illnesses: 81 percent of those incarcerated in state facilities had prior sentences.

The Justice Department statistics are relevant to Vermont because a significant percentage of Vermont prisoners have mental illnesses. The Vermont Department of Corrections can’t provide an annual average – the prison population is constantly in flux, individuals enter and leave treatment and prisoners have widely varying diagnoses – but on August 20, 2007, the department took a “snapshot” of its prison population. It found that day that 34 percent of male and 56 percent of female prisoners had at least one diagnosed mental illness.

People with mental illnesses are also over-represented among offenders on probation and parole and, “They are twice as likely as people without mental illnesses to have their community supervision revoked,” according to a study by the Council of State Governments Justice Center.

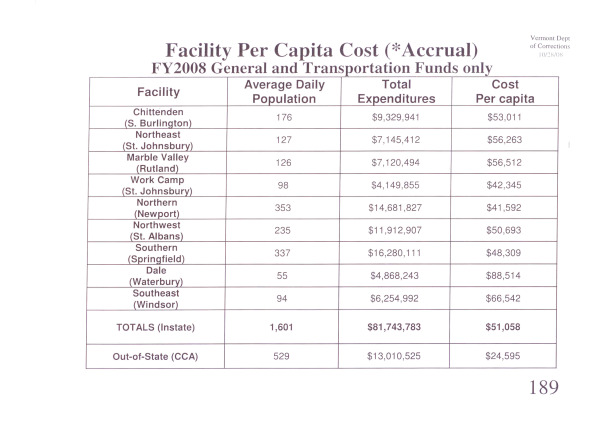

There are compelling reasons to address recidivism, notably the soaring cost of incarceration. Between 1996 and 2006, the number of people in Vermont’s prisons doubled, although crime rates did not increase, and between fiscal years 1996 and 2008, Vermont’s corrections spending ballooned by 139 percent. The Justice Center identified high rates of recidivism as a factor contributing to the rapid growth of the prison population.

“This is bankrupting our state,” said John Perry, former Director of Planning for the Vermont Department of Corrections in an interview on CCTV last summer.

The risk factors that predict recidivism for people without mental illness are the also the best predictors of recidivism for those who have a mental illness, the study says. People with mental illnesses have more of the risk factors, however, plus additional ones associated with their illnesses, such as functional impairments – developmental disabilities, traumatic brain injuries or dementia or other neurological disorders.

The study notes that many also face social and economic problems such as homelessness, and most have substance abuse disorders.

In fact, the Justice Center notes that “two-thirds of property and drug offenders in need of substance abuse treatment report (have) received mental health treatment in the past.”

There are reasons besides the high cost of incarceration to keep people with mental illnesses from recycling through the state’s prisons.

One is uncertainty about the result.

“The prison environment is essentially un-therapeutic and therefore may exacerbate underlying conditions such as mental illness,” said the Corrections Inpatient Work Group in its 2008 Futures Report. “Some work group members questioned whether long-term incarceration is even appropriate for offenders with mental illness who have committed non-violent, victimless crimes, and support diversion programs as an alternative to just locking people up, when their primary need is to access community-based treatment.”

“The limitation of treatment options and the incarcerative environment are a combination that can result in allowing people to essentially fall of a cliff … rather than to receive appropriate mental health services geared toward recovery,” the authors of the report added.

Recent Vermont efforts to reduce recidivism have focused on providing more effective care for offenders in the community through collaborations within the Agency of Human Services and beyond it.

In January 2006, Cynthia LaWare, then secretary of the agency, piloted the Offender Reintegration Initiative. The goal of the program, advocated by the Vermont Association for Mental Health, was to ensure that when offenders are discharged, they will have in hand the benefits they are eligible for, rather than having no way to meet their basic needs.

LaWare sent eligibility specialists from the Economic Services Division into three prisons to help prisoners scheduled for release sign up for programs such as 3SquaresVT (formerly known as Food Stamps), the Vermont Health Access Plan, Reach Up and other benefit programs.

The Reintegration Initiative has since been extended to all correctional facilities, as well as to the Vermont State Hospital. The interviews will soon be conducted by telephone, which will cost significantly less.

As the result of the collaboration between the Department of Corrections and Department of Motor Vehicles, offenders are now given cards identifying them as Agency of Human Services’ clients when they leave prison. The photo IDs are accepted by banks, so offenders can cash checks and open bank accounts.

Thanks to a project of the Department of Disabilities, Aging and Independent Living, disabled prisoners receive Social Security Income (SSI) benefits as soon as they are discharged, so they can pay for food, clothing and shelter.

There is no way to track the effect of these initiatives on the recidivism rate, but the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law lists all of them as “best practices.”

Efforts are also underway to improve coordination of services between the Department of Corrections and the Department of Mental Health.

Corrections officials are now reviewing proposals for prisoner medical and mental health services from contractors who use electronic health records.

“It’s going to be predominately for the prisons,” Corrections Commissioner Andrew Pallito said, “but I think it will be useful for somebody who’s in our system who’s going back out on the streets and getting treatment in the community.” Pallito added that electronic health records will also make it easier to see where the department is meeting community standards of care (and where improvement is needed).

For the past six months the Department of Mental Health has been gathering data related to the issue of recidivism. The data address questions such as the percentage of people in different parts of the state who received community substance abuse or mental health services while they were under corrections supervision and whether they were eligible for Medicaid.

“There isn’t a lot of data on this population – real data about the people who are actually involved with Corrections – because Corrections doesn’t take in as much data,” said Michael Hartman, Vermont’s commissioner of mental health. In addition, Hartman said, “There was a lot of question about whether there were any services, and there was a real lack of data on whether there was or not.”

The goal of the research, he said, is “to get a snapshot of what kind of services people might need, what kind of services we might be able to provide, where’s the funding for it – those kinds of questions.”

Ultimately, Hartman hopes to learn what his department can do “to move folks who may get stuck in corrections because of their disability” back into the community and “once they’re in the community, what kind of services can you give to help them stay there.

“What we’re all trying to explore is if we could come up with the right combination of programs, could corrections close beds and that money be channeled over to doing treatment,” he explained.

Meredith Larson, chief of mental health services for the Department of Corrections, stressed the importance of good release planning, particularly for prisoners who have serious functional impairments.

But Larson doesn’t think release planning is a magic bullet. Noting the extreme difficulty of reintegrating some prisoners with serious functional impairments into the community, she declared, “It’s very complicated. There are just tremendous hurdles to … providing the services that have some chance of stopping the revolving door.”

Read more in our series about the treatment of the mentally ill in Vermont’s criminal justice and prison systems:

Prison is a tough environment for mentally ill

Officials say suicidal inmates watched more closely

Court mandates psychiatric treatment for offenders instead of jail time