Economist: 150 farms could go out by next summer

You’ve read the headlines. The dairy industry is in crisis. Milk prices have fallen to 30-year lows. Worldwide demand for cheese and powdered milk has plummeted because of the global recession. Farmers are eating into their equity to survive.

But how bad is it, really?

If you didn’t know any better, you might assume the current downturn is like the others because every few years, the bust cycle recurs: Farmers hit the skids and politicians sound the “crisis” alarm.

Vermont, after all, has been losing dairy farms by the hundreds for decades. We had 11,206 farms in 1947; 4,153 in 1970; and today we’re down to 1,046.

This downturn, however, is different.

Vermont Agency of Agriculture officials, agricultural economists, farmers and suppliers – normally a stoic lot — are uncharacteristically throwing around words like “dire” and “scary.” Rep. Peter Welch told a House agriculture subcommittee that the dairy industry in Vermont is on the “brink of collapse.”

This time around, state officials and economists say even Vermont’s best farmers might not escape unscathed because of the length and severity of the downturn. They worry about the resilience of the industry as a whole.

With milk prices at 30-year lows, farmers are hemorrhaging money. Market predictions indicate they’ll continue to bleed cash until next summer. No one seems to know, at this point, when milk prices will reach break even, cost of production levels.

“The market doesn’t give any indication of turning around quickly,” says Roger Allbee, secretary of the Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets.

UVM Extension agricultural economist Bob Parsons says the way things are headed, 150 more farms could go under by next summer. The state has lost 32 farms since January.

In addition to the severe slump in market demand, farmers are spending more than ever to make milk, and to stay in business they’re accruing debt at an alarming rate. At the same time, their assets have dwindled as cow and equipment values have dropped, making it more difficult for them to borrow money.

Here are the factors driving farmers to the brink of insolvency:

- For every $3 gallon of milk, the farmer gets 90 cents. The kicker? That gallon costs the farmer $1.80 to produce. In addition to record low milk prices, Vermont farmers are facing higher-than-ever input costs for grain, fertilizer and supplies. Consequently, the gap between the cost of production and the milk price has grown to unprecedented levels, according to Kelly Loftus, communications director for the Agency of Agriculture.

- Farmers have been losing thousands of dollars each month since the crisis began. The cost estimate used by agency officials is $100 per cow per month. A 120-cow dairy on average is losing $12,000 a month; a 700-cow dairy, $70,000 a month. Total losses since February for farms of this size? $84,000 and $490,000, respectively. Add the basic cost of living for a family, $40,000, to that number and you get the whole picture: Without an outside income, those farms are likely to go $124,000-$530,000 in the hole this year.

- Farmers are eating up equity at an alarming rate. Hundreds of dairies are borrowing more money and restructuring their loans to pay for daily operating costs. Farm Service Agency loan volume is up 60 percent this year; Yankee Farm Credit has loaned 19 percent more this year than last.

- Farmers are juggling bills to stay afloat and that means they have thousands of dollars in unpaid bills. Dairy suppliers, particularly grain dealers, are in a bind. They are carrying, thousands and in some cases millions, of dollars in delinquent accounts receivable. Because most of this debt is unsecured, grain dealers are finding it difficult to borrow more money so that they can extend more credit to farmers.

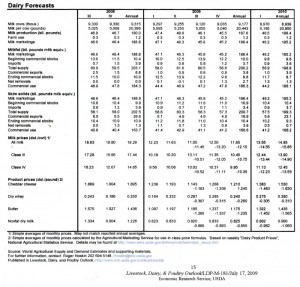

- There is no end in sight. Prices for milk fell below production costs in December 2008 and plummeted in February to $11-$12 cwt, or hundredweight, the equivalent of 11.6 gallons. The average cost of production is $17-$18 cwt. According to USDA Economic Research Service, prices are not projected to reach break even levels until next summer. ERS predicts the average price next year will be $14.65-$15.65 cwt.

Even interventions from the government – low-interest loans and increased spending on federal commodities — won’t be enough to get farmers over the hump, economists and state officials say.

An amendment from Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., that passed the Senate, but has yet to be considered in the House, could raise the milk income loss contract, MILC, a subsidy for dairy farmers, by $1.25-$1.50 a hundredweight, but it has yet to pass. An increase would help farmers substantially, but the subsidy would not bring milk prices back up to cost of production levels of $17-$18 per cwt in the near future.

Sanders says he wants to get at the root problem, which in his view comes down to processors taking huge profits as they pay out a rock bottom price to farmers for raw milk. He has called for a Department of Justice investigation into allegations of price-fixing and anti-trust violations by Dean Foods, which controls 70 percent of Vermont’s milk. Sanders says helping farmers get a fair price for their product is the best long-term solution.

For the short term, however, the crisis has not yet been averted.

Last month Secretary Allbee asked a group of dairy processors to help to create an emergency fund for farmers. They expressed little interest. As a stopgap measure, the agency is launching a fundraising Web site

http://www.keeplocalfarms.org, through which officials hope to funnel donations from the public to farmers.

The Agency of Agriculture has also devoted the latest issue of its newsletter to the dairy crisis, and it reads like a survival guide. About half of Agriview is devoted to human services programs for food stamps, fuel assistance and subsidized health care. There is a list of mental health resources, a pitch for a nonprofit mediation service and a story about how to talk to kids about financial problems. Other articles offer how-tos on filing bankruptcy, auctioning cows and equipment and selling development rights. The agency is promoting these measures as a way to keep farms going under extreme circumstances.

“Farmers aren’t proud to be in the news because we need handouts, because we need more subsidies,” says Marie Audet of Blue Spruce Farm in Bridport. “We don’t like that and we don’t think it’s necessary because we grow an awesome product. We do it efficiently and in a sustainable way, and we shouldn’t be in the news because we need subsidies. There’s got to be another way.”

Audet hopes that the nonprofit group she helped to form, Dairy Farmers Working Together, can push legislation that would enable farmers nationwide to engage in a coordinated supply management system that would help to control the amount of milk available on the market. Audet says this is the only way dairy farmers are going to get a fair price for their product.

Ironically, at a time when more Vermonters are concerned about where their food comes from, local farmers that produce milk are under siege.

As Sanders puts it, “You will end up with a situation where consumers will be dependent on very large farms for their milk or perhaps increasingly dairy products coming from abroad. I think that is a very, very unfortunate scenario because in Vermont people are increasingly concerned about the quality of the food products that they’re eating. They don’t want food from farms in China where regulation is very, very weak for example.”

Copyright, Vtdigger.org