Communities where dairy is king take a hit economically

Dairy farming is the economic engine of small town Vermont, but the industry doesn’t garner the attention paid to monolithic employers, such as IBM and Green Mountain Coffee Roasters.

No one is proposing a Circ Highway expansion for milk trucks, or economic development incentives to keep dairy farmers in state.

Maybe that’s because dairy farmers are too busy working 2,500-3,000 hours a year to advertise their role in Vermont’s economy.

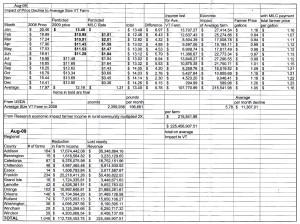

By the numbers, however, dairy farming is one of the state’s economic pillars. It represents 7.8 percent of the state gross product: It will generate about $2 billion in production, employment and business interactions in 2009, according Vermont Agency of Agriculture estimates, out of a total of $26.626 billion for 2009, according to economist Jeffrey Carr, president of Economic & Policy Resources in Williston.

Dairy farmers employ roughly 7,500 Vermonters, more than IBM (around 5,300) and Green Mountain Coffee Roasters (about 1,000) combined and nearly as many as workers as state government (7,970).

What makes dairy seem somewhat inconspicuous is its location – central hicksville. Farms, naturally, are concentrated in the state’s most provincial backwaters: Franklin, Addison, Orleans, Orange and Caledonia counties (in that order).

But Bob Parsons, agriculture economist for UVM Extension, says the dairy operations in these communities are anything but low profile.

“If you (look at) Franklin and Addison counties, the two biggest dairy counties, you either work outside of these towns or if you work in the town, it’s usually at a dairy farm,” Parsons says. “In some of the smaller towns in Franklin County, like Enosburg Falls, dairy is the only game in town.”

If you happen to live in a rural burg where milk producers are king, downturns in the industry are hard to ignore. That’s because in towns like St. Albans and Derby, dairy farm income can represent 25 to 30 percent of the local economy.

Parsons says a 400-cow farm can gross $1 million a year. Even if that farm only makes a 5 percent profit, he says, $950,000 is spent locally on equipment or inputs, such as grain and fertilizers.

“People forget while (dairy) may not be big in Burlington and Rutland and bigger micropolitan areas, in some parts of the state it’s probably a quarter to 30 percent of the activity,” Carr says. “If you look at Franklin County, if you look at Addison County, places like that, agriculture is probably a third of the economy.”

Every dollar generated by local farms moves around the local economy at least twice, says Kelly Loftus, communications director for the Vermont Agency of Agriculture. Farmers purchase 96 percent of their supplies from local vendors and pay more than $68 million in state and local taxes, according to agency estimates. Dairy employs 7,800 workers indirectly.

“Your economy has to be like your retirement portfolio,” economist Jeffrey Carr says. “It has to be diversified. If you don’t have a diverse economy, something happens to one of your big pillars and then the whole economy. Your big pillar catches a cold and the whole economy catches pneumonia.”

When milk prices plummet, so do the fortunes of local businesses in small towns across the state, particularly when dairy losses are as dramatic as they have been this year.

The total impact of industry losses on the state’s economy have tallied up to $225.45 million so far this year, according to ag

ency estimates.

Dairy dependent counties have been hit hardest. In 2009, farm generated income has fallen by $50.4 million in Franklin, $35.3 million in Addison, $31.4 million Orleans, and $18.7 million in Caledonia counties.

“We have these other secondary agriculture businesses, like the seed and fertilizer dealers, the veterinarians, they’re all feeling the effects of this situation,” Loftus says. “And that goes out even further into our communities, whether it’s the car dealerships or the local grocery store, all these businesses in our local communities are feeling the impacts of this dairy crisis.”

There are less tangible spinoffs, too, including tourism, which promotes the farm landscape, Vermont made products and the state’s agricultural heritage, Carr says.

“There’s a synergy there,” Carr says. “Maybe there are only 15,000 quote unquote jobs. That’s very important to certain parts of the state and can’t be ignored. It’s also very important to the Vermont tourism industry because a lot of people expect to see working agriculture when they come here and that’s a big part of their visitation experience.”

Copyright, Vtdigger.org