[W]hen Kate Daloz was growing up in the tiny Northeast Kingdom town of Glover, she didn’t see her childhood as out of the ordinary. Then she went to graduate school in New York City and learned that most families don’t live in a hand-built geodesic dome with an outhouse named “The Richard M. Nixon Memorial Hall.”

“That was the point I realized how much I wanted to know,” she recalls today.

The Columbia University master’s candidate set out to research the back-to-the-land movement, only to find little specific information in the library. Without a book to read, she decided to write one herself.

“We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s on the Quest for a New America” chronicles both her family, friends and neighbors’ migration north and the earlier trails blazed by such pioneering predecessors as 1800s New England naturalist Henry David Thoreau and 20th-century “Living the Good Life” authors and fellow Vermonters Helen and Scott Nearing.

“I realized these personal questions,” she says, “were historical questions.”

Headline-sparking ones, too. Daloz, a former research assistant for Pulitzer Prize-winning biographers Ron Chernow and Stacy Schiff, records how her parents moved from greater Boston in 1971 to hammer together a Vermont home, as well as how a nearby commune flirted with “free love” and marijuana cultivation before police seized nearly 500 plants worth perhaps a quarter-million dollars.

But sex and drugs weren’t the reason the book went viral upon its recent release. Instead, page 146 reveals a visit from a fellow transplant named Bernie Sanders. Then a freelance writer, the current Vermont U.S. senator conducted interviews as a communal leader watched and wondered.

“Even though he agreed with almost everything Bernie had to say, he resented feeling like he had to pull others out of Bernie’s orbit if any work was going to get accomplished that day,” Daloz writes. And so after Sanders stayed for his allotted three days, the communal leader “politely requested that he move on.”

Or, as the headline of the conservative website Washington Free Beacon would report nearly a half-century later: “Bernie Sanders Was Asked to Leave Hippie Commune for Shirking, Book Claims” — a story repeated everywhere from right-wing blogs to the New York Times Sunday Book Review.

“For a second,” Daloz says today, “I thought this was going to be trouble for Bernie.”

It wasn’t. As for her, in the words of Donald Trump, all publicity is good publicity.

“Clearly one person read the book,” the author says, “which I was impressed by.”

Critics are returning the compliment.

“This thoughtful history,” Kirkus Reviews says of the 384-page PublicAffairs hardcover, is “well written and full of firsthand insight.”

‘What was stopping them?’

Daloz opens the book a decade before her birth as the 1960s closed with the chaos of the Vietnam War and assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy.

“All over the nation at the dawn of the 1970s, young people were suddenly feeling an urge to get away, to leave the city behind for a new way of life in the country,” she writes. “Most had no farming or carpentry experience, but no matter. To go back to the land, it seemed, all that was necessary was an ardent belief that life in Middle America was corrupt and hollow, that consumer goods were burdensome and unnecessary, that protest was better lived than shouted, and that the best response to a broken culture was to simply reinvent it from scratch.”

By the fall of 1970, as many as 50 communes sprouted in Vermont; two years later, that number reached as many as 200, the book notes. The state’s population of fewer than half a million people would rise by 15 percent over the decade — “the only moment in the nation’s history when more people moved to rural areas than into the cities, briefly reversing two hundred years of steady urbanization.”

Daloz doesn’t identify her hometown or any neighbor’s last name in the interest of privacy. But everyone she quotes is happy to share how it all seemed so simple.

“There was plenty of groundwater, along with the stream cutting through the bottom of the field across the road,” she writes. “For food, they would have the garden, and it would be easy enough to get chickens and a cow — and goats, of course. To support the animals, they had ample land for pasture, as well as hayfields for winter fodder. … It wasn’t so long ago that people around here had farmed in much the same way — tractors had only really become common here during the 1950s, and electricity and telephone service were still novelties on some back roads. What was stopping them from going back to that now?”

Plenty, newcomers would learn. Before they built homes, many lived in Army tents.

“When the first snows came, the communards made room at the far end of the tent for the cows,” Daloz writes. “Their pleasant body heat and soft animal noises in the night mitigated somewhat the intense smell of manure.”

Soon babies joined the fold. But without a washer or dryer, mothers found themselves tied to a hand-crank washtub and clothesline.

“After you loaded the laundry and the powdered soap into the washer’s tub, you poured in hot water hauled in buckets from the sink and turned the crank to run the agitator,” Daloz writes. “Then, after you dumped the dirty suds and repeated the whole process with a fresh round of rinse water, you fed the laundry one item at a time through the wringer.”

‘Who would have imagined?’

It all took its toll.

“Young back-to-the-landers who had felt reassured by the ‘real’ skills of growing their own food and building their own shelter were now also experiencing what their farm neighbors and forebears had long known: relying strictly on yourself and on the land for your livelihood puts you frighteningly at the mercy of chance,” Daloz writes. “An early frost, a slipped saw blade, a hot-selling market vegetable suddenly passing out of vogue — one stroke of bad luck could be devastating.”

One by one, people departed (or, in her parents’ case, divorced). Yet as they moved on, they took what they had learned with them.

“Every last leaf and crumb of today’s $39 billion organic food industry owes its existence in part to the inexperienced, idealistic, exurbanite farmers of the 1970s, many of whom hung on through the ’80s and ’90s, refining their practices, organizing themselves, and developing the distribution systems that have fed today’s seemingly insatiable demand for organic products,” Daloz writes. “Every YouTube DIY tutorial, user review, and open-source code owes something to the Whole Earth Catalog’s contention that our most powerful resource is connection to each other and access to tools. Every mixed-greens salad; every supermarket carton of soy milk; every diverse, stinky plate of domestic cheese; every farm to-table restaurant, locavore food blog, and artisanal microbrew has a direct ancestry in the 1970s’ countercuisine.”

The back-to-the-land movement also foreshadowed current interest in environmental activism and alternative energy: “Who, even in the ’90s, would have imagined the early-21st-century reality of compost bins at Yankee Stadium?” she adds. “Or organic food on the menu at McDonald’s? Or solar panels on the roof of Walmart?”

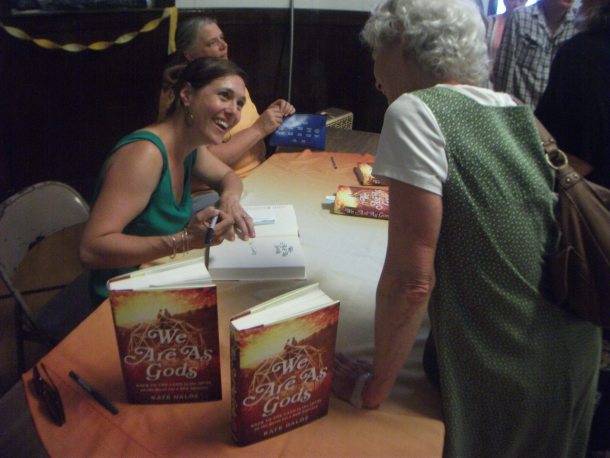

Daloz was equally surprised by a capacity crowd of old-timers and newcomers at her recent book launch at the Glover Town Hall. (Another reading is set for Tuesday at 7 p.m. at Cobleigh Public Library in Lyndonville.)

“This piece of our own shared history represents a genuine chapter of American history,” her father said as he introduced his daughter.

So much so, Daloz has published related articles in Rolling Stone magazine (“How the Back-to-the-Land Movement Paved the Way for Bernie Sanders”) and on Curbed.com (“There’s No Place Like Dome: How America’s Back-To-The-Land Movement Gave Rise To The Geodesic Dome Home”).

“It would be decades before (my parents) even realized they’d been part of a huge demographic surge, never mind participated in something called a ‘movement’ without even realizing it,” she writes. “At the time, the idea of living simply and close to the earth just felt like a natural solution to their own particular problems and desires.”

As for herself, the author is raising a family in Sanders’ old New York borough of Brooklyn. On days of winter whiteouts, she tells people she appreciates the walkable city full of diverse color and culture.

“But when I come home to Vermont this time of year and someone asks why do I live in Brooklyn,” she concludes with a laugh, “I can’t remember.”