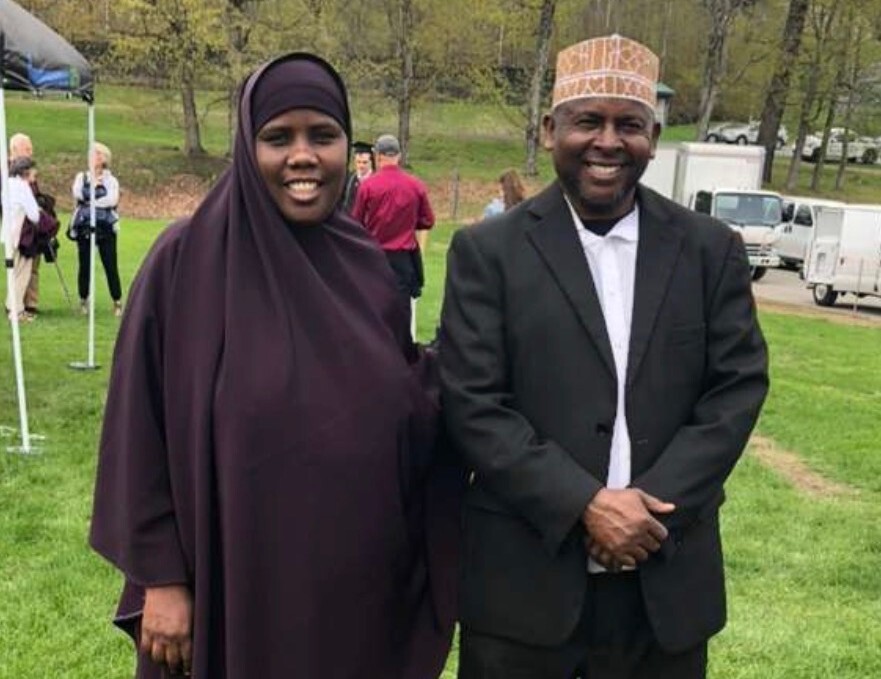

Burlington-area community members plan to rally next week to support a longtime Somali resident who was detained by federal immigration officers at the airport on New Year’s Day.

Hussien Noor Hussien, 63, has been held at the Northwest State Correctional Facility in St. Albans since. The rally coincides with his next scheduled hearing at U.S. District Court in Burlington at 11 a.m. Wednesday.

Hussien’s friends and neighbors said the resident, husband and father was unfairly targeted by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement while he was driving his taxi. He runs Freedom Cab, a taxi service.

Hussien came to the United States as a refugee in 2004. He has a wife and five children, ages 3 to 17, who are all U.S. citizens, and has lived in Vermont for 13 years, according to court documents.

“He is a very respected elder in our community,” said Abdirisak Maalin, a Burlington resident and family friend. Maalin helped Hussien file a complaint in federal court on Jan. 8 asking for his release.

“He’s someone who people go to for their problems — family disputes or people needing advice,” Maalin said.

Hussien’s detention continues amid escalating ICE activity targeting Somalis in Minnesota and more recently in Maine.

His case is complicated because he was already in deportation proceedings from a prior case when he was first detained by ICE.

Hussien became a legal permanent resident of the U.S. in 2007 and a naturalized citizen in 2011, according to court documents. He moved to Vermont in 2013 and applied to legally change his name to his birth name, Hussien Noor Hussien.

He had used a different name for the naturalization filing and was convicted in 2019 for impersonating another and making a false statement on his passport application. He was sentenced to three months in prison and three years of supervised release, according to court documents.

Hussien adopted a relative’s name in Somalia to avoid being forced to participate in the militia of a war-torn country as a young man, Maalin said.

ICE detained Hussien immediately after his release from federal prison on Jan. 9, 2020, and began deportation proceedings. He was released in April 2021, has met all the conditions of his release and was granted protection from detention for a year, according to the complaint filed.

Hussien reapplied for permanent residency in 2021 and got his green card in 2023, which is valid until 2033, according to court documents. He had an immigration court date scheduled for April 2027.

“He had been living in complete compliance with his terms of supervision, which were fairly rigorous, without any complications,” said Brett Stokes, a lawyer at the Vermont Law and Graduate School’s Center for Justice Reform Clinic, who is representing Hussien and who hopes the judge will hear the argument for Hussien’s release next week.

On Jan. 1, Hussien drove his van to the taxi lane outside the Patrick Leahy Burlington International Airport and was waiting for business when ICE officials drove up and detained him, as first reported by the Vermont Daily Chronicle. He complied and was driven to the Northwest State Correctional Facility.

Details of his arrest are limited, the complaint states.

Hussien alleges in his complaint that he was held in solitary confinement since Jan. 4 with no explanation given. A practicing Muslim, he was denied basic accommodations such as a Quran, a prayer mat and a clock, without which he was unable to figure out the time for prayer, in violation of his fundamental rights, according to the court document.

A community concerned

Hussien is “a pretty remarkable person,” who filed the writ of habeas corpus challenging the recent arrest and detainment himself, Stokes said.

There was no point in detaining and arresting him again, said his friend Maalin, a Somali American and assistant executive director of the United Immigrant & Refugee Communities of Vermont, an organization he co-founded.

Hussien has never missed a court date, so it was “very unfortunate” that ICE “out of nowhere, with no warrant, just came to pick him up from his place of work,” Maalin said. “That’s just to harass the community.”

“His detention raises serious concerns about fairness, proportionality, and the human cost of immigration enforcement, especially when it disrupts families and removes individuals who have complied with the law and built their lives here,” states a post on UIRC’s Facebook page. The organization is accepting donations to help Hussien’s family.

ICE announced Hussien’s arrest as a “criminal alien from Somalia” via a social media post and photo of Hussien in handcuffs flanked by two agents on Jan. 2. The post misspelled Hussien’s name and tagged a right-wing social media user whose allegations of day care fraud by Somalis in Minnesota led the Trump administration to freeze child care funding to the state earlier this month, NPR reported.

ICE officials did not respond to a request for comment on Hussien’s case Thursday.

President Donald Trump’s crackdown on immigration has targeted the large Somali population in Minnesota. Trump has made disparaging comments about Somalis and exchanged barbs with Minnesota U.S. Rep. Ilhan Omar, who is of Somali origin.

Maalin and others in the greater Burlington area see Hussien’s detention as a local example of what they call anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim and anti-Black rhetoric being used at the national level to target people of color, particularly Somalis. Notably, Trump in December called Somali immigrants “garbage” and said “we don’t want them in our country.”

After civil war broke out in Somalia in 1991, the U.S. approved Somali refugees resettlement in 1999 and Vermont in 2003. About 300-400 Somali families are estimated to live in Vermont.

Stokes can’t say if Hussien was targeted for being a Somali.

“But given the timing of everything … it’s hard to not think that it could be related. So I understand that the community is concerned,” he said.

Maali, however, is convinced Hussien was targeted because he is Somali and that his arrest sends a chilling message to Somalis in Vermont who are already fearful given the national climate.

Winooski is home to many of Vermont’s Somali residents. Approximately 9% of the families served by the school district identify as Somali, according to Superintendent Wilmer Chavarria, who said their safety and well-being remains their highest priority.

“Given recent events, both nationally and here in Vermont, it is understandable that members of our school community are experiencing concern and anxiety,” he said.

Burlington resident Cindy Cook, one of the organizers of the rally, said she heard about Hussien’s detainment from a neighbor and friend who is Somali and “just jumped into overdrive” to help him.

“He’s got so many dependents who are radically affected by losing the breadwinner of the family,” she said.

A few years ago, Cook started a group called Chittenden County Welcoming Committee to help support and serve the immigrant community as part of the Welcome Corps national program. The Trump administration suspended that program last year. Cook has since partnered with the Community Sponsorship Hub and Maalin’s organization to continue to help new Americans in Chittenden County.

She is organizing mutual aid for Hussien’s family and is looking for help to deliver meals, collect money for rent, utilities and groceries, provide emotional support and send letters to Hussien. And a Reddit post seeking help for a neighbor “kidnapped by ICE” has more than 400 comments.

Lars Gold, a public school teacher at South Burlington High School, got involved with the rally because they know the Hussiens, who currently have four children enrolled in the school district. The eldest son was a coach and worked with Gold at the high school.

The detention of a longtime resident and community member is “incredibly harmful,” and South Burlington is “heartbroken” for it, Gold said.

Gold, who is the co-grievance chair of the South Burlington Educator’s Association and member of the collective Vermont School Workers United, has also been in touch with the family since Hussien’s detention, spreading the word among colleagues and harnessing help to provide mutual aid “during this very, very challenging time.”

“They are obviously deeply upset by the sudden and harsh absence of their father, and they have been very keen on spreading the word of this injustice,” Gold said.

For being incarcerated, Hussien is doing well, according to his lawyer.

“He comes with a lot of community support. A day doesn’t go by that I don’t get an email from a new person wanting to try to figure out how to help him,” Stokes said.

Correction, Feb. 5: A previous version of this story misstated Abdirisak Maalin’s title at the United Immigrant & Refugee Communities of Vermont.