Kellen Appleton is a regular rider on the Advance Transit buses that run in and around her hometown of Lebanon, New Hampshire. But recently, Appleton got to thinking: How far could local buses, like the ones she relies on in the Upper Valley, really take her?

Earlier this month, she set out with her housemate, Ana Chambers, to put the question to the test — at least, within the confines of Vermont. The duo rode what they think was the longest-possible trip across the state, within a single day, using only public buses.

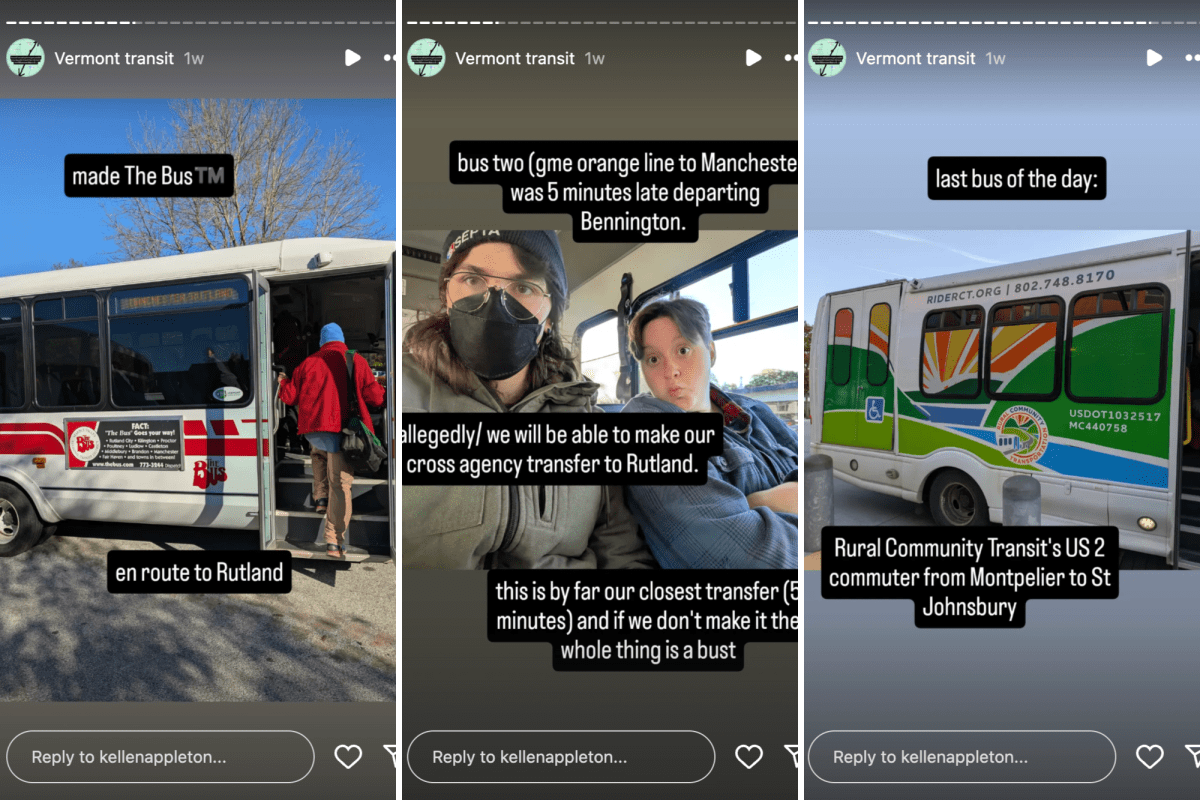

The journey, which Appleton documented on Instagram, started just below Vermont’s southwestern corner in Williamstown, Mass. Eleven hours and seven different buses later, they made it to St. Johnsbury in the heart of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom.

The goal? To “kind of push the public transit system to its limits,” said Appleton, who works for a regional planning commission based in Weathersfield, Vermont, in an interview.

There are certainly more convenient ways to get across the state, even using transit. Amtrak runs two trains through Vermont that ultimately connect to New York City, for example, while Greyhound buses traverse the state between Boston and Montreal.

But Appleton said she and Chambers wanted to make their trip as challenging as possible by relying only on public transit that, unlike Amtrak or Greyhound, could not be booked ahead of time. They also wanted to use routes that ran on fixed schedules, which ruled out using microtransit services that can be called on demand.

In all, they paid just a single, $2 fare the entire day — “a bargain, right?” she said.

Appleton and Chambers’ trip started with a 7:15 a.m. ride on The Green Mountain Express’ Purple Line from Williamstown, Mass., north across the state line to Bennington. From there, they caught a Green Mountain Express Orange Line bus to Manchester, and then a ride on The Bus, run by the Marble Valley Regional Transit District, into Rutland.

From Rutland, they took a Tri-Valley Transit bus to Middlebury, then another bus from that same operator to Burlington. From there, they rode a Green Mountain Transit Montpelier LINK Express bus to the capital. Finally, from Montpelier, they took Rural Community Transportation’s U.S. 2 Commuter to St. Johnsbury, stepping off for the last time at 6:30 p.m.

Appleton said she was pleasantly surprised by how it was possible to make so many different bus connections throughout the state. It was a testament to the local transit agencies, she said, that each bus ran close enough to its listed schedule that she and Chambers could actually stick with the route they’d carefully planned ahead of time.

She noted, though, that some of the agencies’ schedules aligned for a transfer only once a day — or left just minutes to spare — meaning a single substantial delay could have scuttled the plan. That’s hard to complain about for a trip, like theirs, that was fairly impractical by design, she said. But she added that the “fragile” nature of parts of the itinerary underscored how difficult it can be for many people to rely on public transit for their needs.

Having more regularly scheduled bus service, especially serving rural communities, could encourage more intercity trips without a car, Appleton said.

Vermont spends more money on public transit than other similarly rural states, according to a 2021 report, though state lawmakers continue to debate whether to increase that funding in an effort to help the state make progress toward its climate goals.

Frequent transit service is “something that’s going to help a lot of people take that leap from, ‘I need to have a car to be independent and be a functional person as a part of society,’ to, ‘I can rely on the systems that we’ve put in place here,’” she said.

At the same time, she noted every bus she and Chambers took had at least one other person on board. While many transit routes are scheduled around commuters traveling only in the morning or the evening, she said, the trip was a reminder that there are people, who likely don’t have cars, using those services at all times of day.

She documented some of the day’s more memorable characters in an Instagram post. That included a man in Bennington, clad in a rainbow bomber jacket and white stone earrings, who was accompanying his young daughter — herself in a fur coat — on the bus to school. Two friends realized onboard, excitedly, that they were taking the bus to the same destination: a methadone clinic that opened in Bennington earlier this year. Three other riders from the Bennington area, all in high school, spent the ride discussing “the fall of communism,” Appleton recalled.

In Rutland, three friends boarded the bus and, with reggae music playing from a phone, unpacked a very different topic — which version of the video game series “Grand Theft Auto” was the best. Another rider worked at a cafe in Middlebury and, upon being asked if the cafe still served ice cream in October, responded: “Hell yeah we are. Follow me.”

A “harried commuter” with a tattoo of Bernie Sanders boarded in Montpelier, Appleton recalled, traveling with an electric bicycle and “alternating sips of coffee, ginger ale, and water the entire bus ride.” The bus to Burlington, meanwhile, had a student on board who revealed the purpose of his visit to a friend just before stepping off, Appleton wrote: “I’m here to see my BOYFRIEND.”

The trip, which would take about three hours by car, also gave Appleton and Chambers a new perspective on towns they might have driven through before — but had never been able to take the time to look around, Appleton said. She said the trip was inspired, in part, by a genre of YouTube videos that feature people taking similarly impractical trips on public transportation and sharing the sights along the way.

“Now, I have some touch point, or some anecdote, or have some connection, to (each) place — and that makes me feel like I’m a little bit more at home than I would be otherwise,” she said.

“Was it practical? No. But like, was it a great time? 100%.”