Vermont Agriculture Secretary Anson Tebbetts asked the federal government earlier this week to issue a secretarial disaster designation for the entire state of Vermont to help farmers cope with the impacts of a persisting drought.

The disaster designation, which the federal government recently issued for Orange and Windsor counties and may soon expand to Addison, Caledonia, Rutland and Washington counties, would make emergency programs and financial assistance widely available to farmers across the state.

Tebbetts asked for the designation in a letter Tuesday that outlined some of the impacts farmers are experiencing, including dead pasture, reduced or nonexistent production of corn, hay, and feed, emptied wells and streams, and diminished vegetable and fruit crops. The lack of feed and the production losses will continue to impact farmers and compromise regional food security, he wrote in the letter.

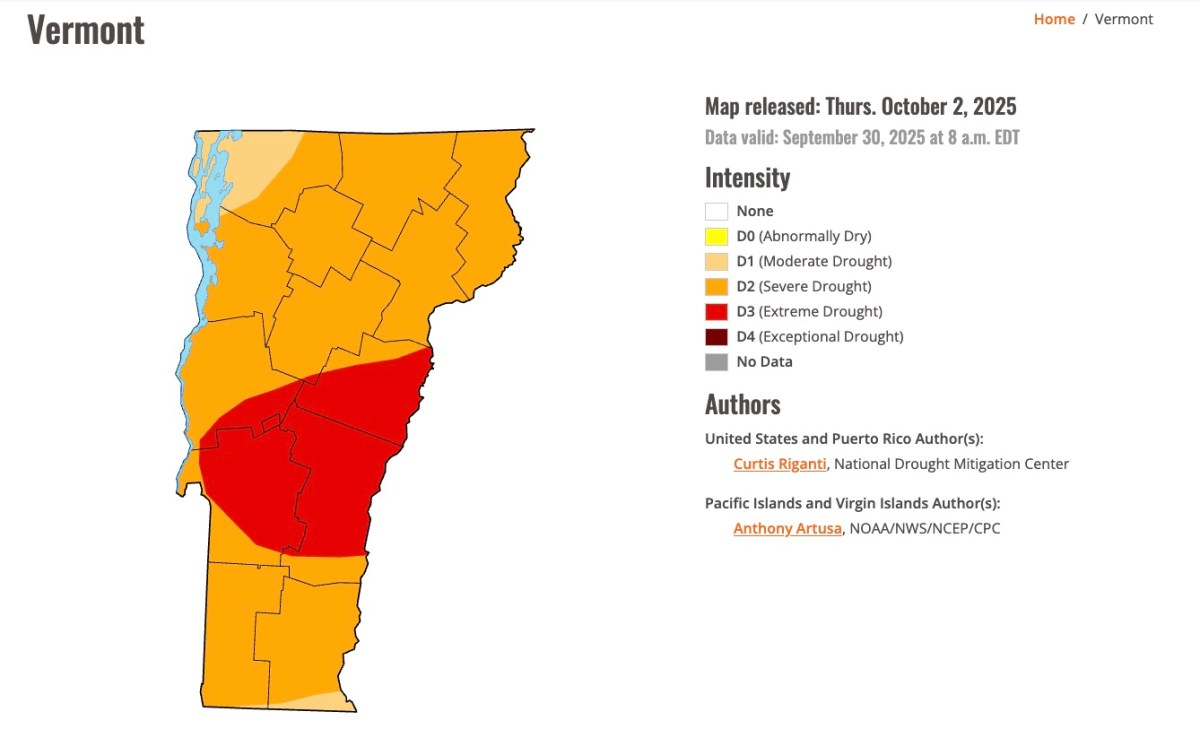

The U.S. Drought Monitor, which analyzes drought conditions, shows that as of Oct. 2, almost 94% of Vermont was in severe drought and almost 24% in extreme drought.

To determine whether to issue the designation, Tebbetts said the U.S. Department of Agriculture will look at how many weeks the state has been in a drought and whether the neighboring counties and states have also received a designation. He said the department would also consider farmers’ economic losses.

“The federal government, the USDA local offices are recording their losses. So, we’ve been working together with the state director, Wendy Wilton, on asking for this request,” Tebbetts said.

The Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets is also planning to launch a survey for farmers to collect specific data on their economic losses, as has been previously done to record flood impacts, according to Tebbetts.

The disaster designation would open up the possibility for farmers to apply for emergency loans and receive fundings through various programs that become available in case of drought, such as emergency assistance for crops, livestock, and honeybees’ losses.

“Sometimes these things are turned around pretty quickly,” Tebbetts said, adding that the agency hopes to receive a response from USDA in the coming days.

However, with the recent government shutdown, nearly half of the employees at the U.S. Department of Agriculture have been placed on furlough. According to the department’s contingency plan, during the lapse of funding, the agency will stop activities dedicated to disaster assistance payments and programs. The plan also estimates 6,377 of the 9,468 employees of the Farm Service Agency, which supports farmers with disaster relief, loans, and conservation programs, among other things, have been furloughed.

Vermont FSA local officers could not be reached for comment. An automatic email reply from Wendy Wilton, FSA state executive director, stated: “I am on furlough without access to email, due to the lapse in federal government funding. I will return your message as soon as possible once funding has been restored.”

‘That could be too late for some farmers’

Richard Nelson, a dairy farmer in Orleans County in the Northeast Kingdom, said part of his farm’s corn crops died because of the drought and some of the corn stopped growing after a frost in mid-September, halting the development of the grain. “We’ve been growing corn for 58 years, and this is the most severe drought we’ve ever seen,” he said.

“There’s a saying in farming that a dry year will scare you, but a wet year will starve you,” Nelson said.

In 2023, the farm lost 300 acres of corn because of the flood and 400 more acres were ruined, according to Nelson. “This year, for us, it’s a quality issue almost more than anything else,” he added.

Nelson expects economic losses of about $800,000. He said the farm won’t be able to produce any grain this year, so he will have to import it from outside of Vermont.

But at least the farm has enough feed for the cattle. “We’re one of the lucky ones because we will have enough forage,” he said. “I have friends in Addison County, and it’s a lot different there and a lot worse.”

Brian Kemp, who manages a large dairy heifer raising operation in Addison and Rutland counties, said his corn crops were also affected by the drought.

“We’ve had other droughts in the past, but not to this extent,” he said. “Not lasting this long and having this much of an effect on the crops.”

May was excessively wet, Kemp said, so the farmers couldn’t plant until June. Shortly after, the drought started.

“Things were planted late, and once they were planted, we just quit getting rain,” he said.

Since there is nothing growing on the pastures, Kemp said, the farm had to use winter surplus feed for the cattle.

“We have 500 animals on pasture. We have been supplementally feeding them grass haylage on the pasture now for at least five or six weeks,” he said. “Typically, we have enough pasture ground that we do not have to supplement.”

Kemp expects his losses to be in the tens of thousands of dollars since they will have to buy more corn to compensate for the scarce corn harvest.

“If we go into winter this dry, like we currently are, it’s a little scary to think about what we would have next year, you know, what type of growing season we would have,” Kemp said.

The farmer said he might consider applying for some form of disaster relief if any program becomes available, but he wasn’t sure yet.

“These programs are great as long as they’re readily available for farmers when they need them and not six months down the road,” Kemp said. “That could be too late for some farmers.”