A special Chittenden County program that convenes addiction recovery resources in family court will shutter at the end of the year due to a lack of federal funding.

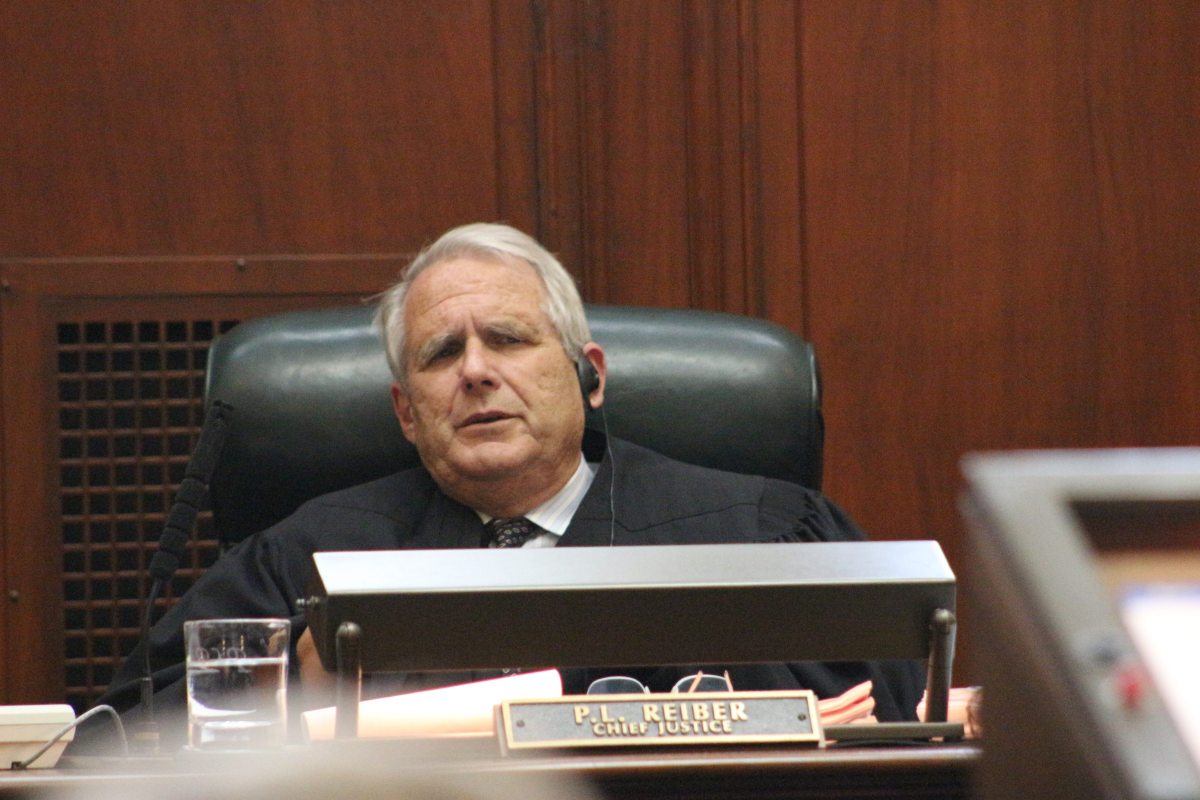

Vermont Supreme Court Chief Justice Paul Reiber announced the family treatment docket’s end in a Sept. 10 letter.

In 2018, spurred by the state Supreme Court, the Vermont Judicial Commission on Family Treatment Dockets began studying ways for the legal system to address the burgeoning opioid epidemic and its impact on children. At the time, abuse and neglect cases in family court were skyrocketing, up 68% between fiscal years 2013 and 2018, according to the commission’s report.

The commission’s work helped launch the Chittenden County family treatment docket in 2021, the only program of its kind in Vermont currently, though the model is used across the country. Other special treatment dockets exist in Chittenden, Rutland, Washington and Windsor counties, according to the state judiciary’s website, but those programs aren’t operated within family court and tend to involve people who have already pleaded guilty to certain crimes.

The family treatment docket seeks to steer eligible family court cases toward treatment and services. Parents in the program have often, through legal intervention, lost full custody of their children. In order for a case to be referred to the program, all parties need to agree that the goal would be to reunify the parent with their children if not for substance use standing in the way.

The docket’s mission is to “improve the safety and well-being of children who have experienced abuse, neglect, or have been placed at risk of harm due to a caregiver with a substance use disorder,” according to Reiber’s letter. Toward that end, the special docket helps lead participants to substance use and mental health treatment, housing assistance and parenting coaching.

The program is funded solely through a three-year grant from the U.S. Department of Justice, according to the letter, a source the court expects will dry up by the end of the year. Vermont received a nearly $900,000 grant to fund the docket, which had annual operating costs around $300,000, according to Teri Corsones, Vermont’s state court administrator, who added that one court position hired specifically for the program would end.

“Under past experience we anticipated that DOJ would have issued a new round of solicitations for federal funding by now, but to date there has not been one,” Reiber wrote.

“We want to be clear: the decision to suspend the program if there is no funding is not a reflection of the program’s value or effectiveness,” he wrote. “It is a reflection of the financial reality we face.”

The docket has seen relatively sparse use — there are currently six participants, according to Corsones. As of April, 33 parents had participated in the docket, incorporating a total of 55 children, since its creation, according to a report conducted by the public policy organization Children and Family Futures.

The report noted that children who reunified with their parents after their parents’ participation in the program spent less time in out-of-home settings than children who were ultimately adopted and not reunified with their parents. As of April, just more than 20% of participants successfully graduated from the docket, and 30% remained active participants, according to the report’s findings, while just under 49% of parents did not complete the program.

The Chittenden County State’s Attorney’s Office is “devastated” that the docket is ending, Sarah George, the county’s top prosecutor, wrote in an email.

William Gardella, a Chittenden County deputy state’s attorney who primarily handles the county’s child-in-need-of-supervision cases, or CHINS, said the family treatment docket empowered the court to do something rare.

“The court is actually trying to solve a problem and repair a relationship,” he said.

Rather than ordering treatment, which might occur in a regular family court case, the family treatment court brings peer advocates into the process from the addiction recovery nonprofit Turning Point Center of Chittenden County and staff from the Howard Center, a social services organization.

“All the service providers that DCF wants you to work with, they’re bringing them to you,” Gardella said, explaining how the docket cut through road blocks to accessing treatment.

Gardella said the program has been operating at full capacity over the last year or so. Participants, service providers and court officials meet regularly — weekly, every other week or monthly depending on the case, according to Gardella. Peer support is central to the process as well.

“We’ve heard about hiking groups starting out of this program,” he said, “ongoing connections that people were going to build to look out for people in the community.”