The Brattleboro Reformer gushed with pride on Jan. 10, 1922. Just the day before, the newspaper proclaimed, workers had started to build a ski jump in town that would be “the best in this country.” The facility’s aggressive design, which featured a longer “in run” area for skiers to build up speed and a greater drop than other facilities in the Northeast, guaranteed that competitors would shatter records set at the famed jumps at Lake Placid and Dartmouth College, the paper stated.

It was a bold statement given that organizers had allowed themselves less than a month to finish construction before a major competition being planned for Brattleboro. That event, scheduled for Saturday, Feb. 4, aimed to attract some of the best ski jumpers in the East.

The ski jump was the brainchild of Brattleboro resident Fred Harris, who caught the ski bug early. Harris was something of an evangelist for the emerging sport and would eventually be called “the man who put America on skis.”

Harris had been introduced to skiing as a teenager by a local doctor, who gifted him a pair of skis. But Harris soon needed another pair, and another, and another. He was curious to try new designs and he was also a daredevil with a habit of snapping his massive skis which, typical of that time, measured up to nine feet long and were about five inches wide. Skis weren’t the easiest things to come by, either. The best had to be shipped all the way from Norway. So Harris found a local woodshop to fashion skis to his specification. For bindings, he purchased leather straps from a harness maker and screwed them to his skis. He would then buckle the straps to his heavy boots. To steer, and to slow his descent, he used a single, nine-foot-long pine pole.

Harris was interested in more than just skiing downhill. He also wanted to catch some air. “Could clear 15 feet,” he wrote in his diary on Feb. 17, 1904, when he was 16 years old. A year later, he could soar 50 feet.

Enrolling at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, Harris was dismayed to learn that there was no winter sports scene. Students seemed to view winter as something to be endured rather than enjoyed. In 1909, when he was a junior, Harris wrote a letter to the college newspaper, calling for the formation of a club to stimulate interest in winter sports by organizing ski and snowshoe trips, building a ski jump, and hosting an annual field day of competitions.

“By taking the initiative in this matter,” he wrote, “Dartmouth might well become the originator of a branch of college organized sport hitherto undeveloped by American colleges.” Harris was right. The Dartmouth Outing Club that he founded changed the college’s winter culture, created the school’s ski teams, and helped launch ski jumping and cross-country and alpine racing as national collegiate sports.

Harris soon decided that instead of holding a winter field day, Dartmouth should host a winter carnival, a weekend of intercollegiate winter sports competitions mixed with social events. The carnival was a success and other colleges in cold climes soon followed suit.

Harris credited the idea of a winter carnival to James P. Taylor, assistant principal of the Vermont Academy in Saxtons River, with whom he once chatted on a train. Taylor, who couldn’t help but notice the 9-foot-long skis Harris was carrying, told him about the winter carnival he had just organized at his school. Inspired, Harris adapted the event for Dartmouth. (At the time, Taylor might already have been pondering another outdoorsy project, founding the Green Mountain Club, which he did months later. As secretary of the GMC, Taylor would lead construction of Vermont’s Long Trail.)

After graduating college and serving as a pilot in the Navy Air Corps during World War I, Harris returned to his hometown with the dream of building a world-class ski jump. He pitched his idea to local businessmen, and they fronted the $2,000 cost estimated by D.W. Overocker of Fallkill Construction, which specialized in road construction.

Harris knew the perfect location for the jump: a ridge, slope and field located partly on an estate owned by a wealthy, local family and partly on land owned by the Brattleboro Retreat, a psychiatric hospital. Men employed by the estate and by the Retreat cut a swath of trees 20 feet wide from the top of the hill past the jump site to the foot of the hill. From there, they widened the swath to 60 feet to allow for a larger landing area. The surrounding trees were left in place to shield jumpers from the wind. The field at the foot of the hill was large enough to accommodate as many as 3,000 spectators.

Ten days into construction, the contractors needed more workers to meet the hard deadline. A notice in the Reformer read: “WANTED—Twenty more men on Brattleboro ski jump.” Anyone interested was to contact Overocker.

By the end of January, work was wrapping up. But there was an urgent need for more help to provide what nature had not—enough snow to hold the event safely. “It is very much desired that a large number of men and boys volunteer to help shovel snow on to the course,” the Reformer reported on Jan. 30. “It will be necessary to cover 300 feet of the course to a depth of two feet. Men and boys with baskets and shovels are wanted at once, the sooner the better.”

By Feb. 2, just two days before the competition, the jump was finally ready for testing. The first trial jumps were made by Fred Harris and his younger sister, Evelyn.

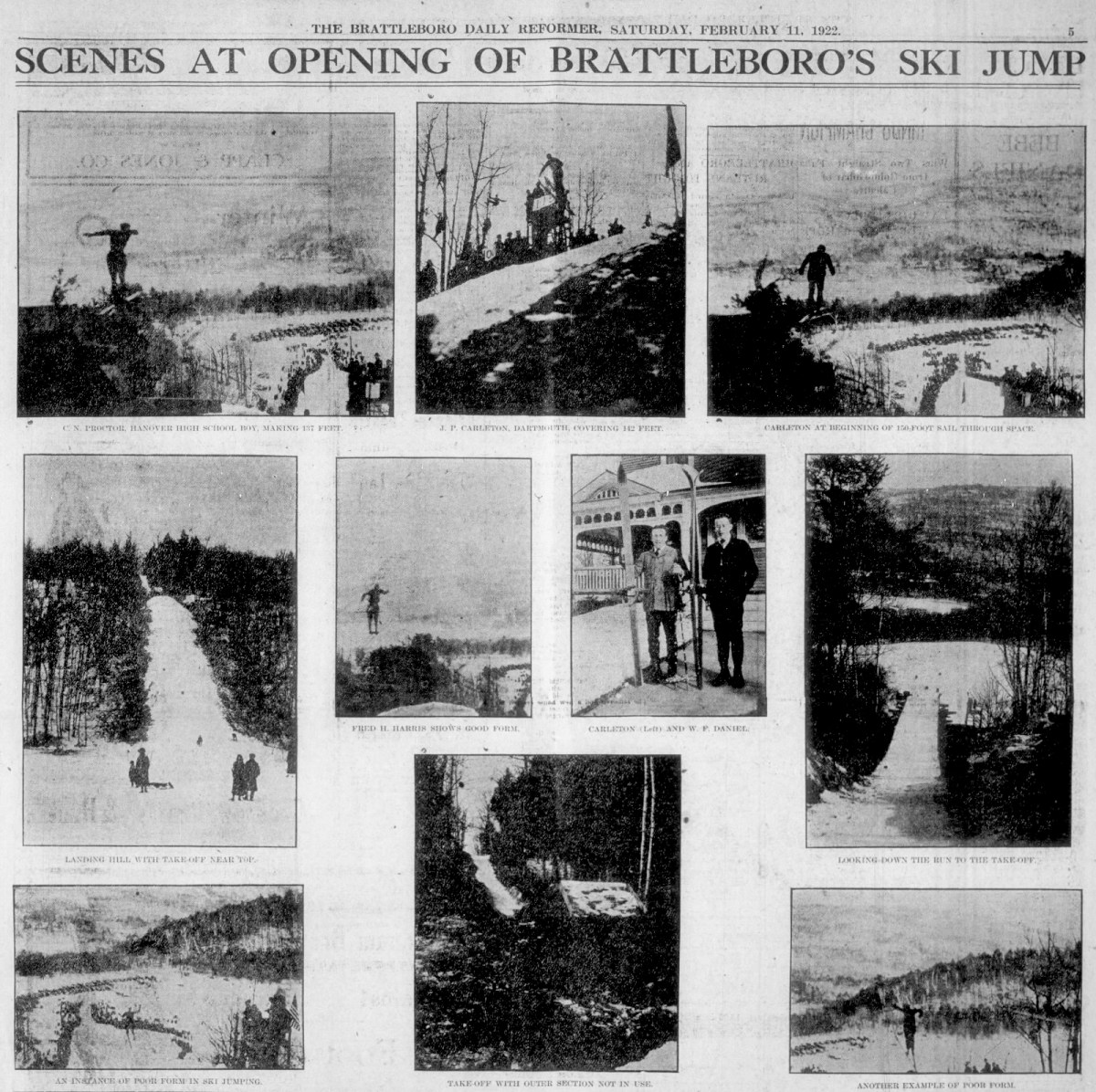

On the day of the event, the Reformer listed some of the talented young jumpers who competed. Among them were Dartmouth student John Carleton, who had set a New England record in January; Ingvalli “Ping” Anderson, who had broken Carleton’s record just the day before; and Gunnar Michelson, a “star jumper” from the Nansen Ski Club in Berlin, New Hampshire. Michelson, the paper noted, “was knocked unconscious on his first jump at Berlin yesterday, falling after he had landed, but he is on deck for today, having arrived here this morning.”

Competitors and spectators poured into Brattleboro. Vermont Lt. Gov. Abram Foote had arrived on the early train, having left Middlebury the night before. He was representing Gov. James Hartness, who was at home recovering from a recent bout of pneumonia. Foote and a few others sat on a platform located just below the bottom of the jump, while some others lined the hillside to watch the jumpers fly past them. Some spectators scurried up trees to get a better view. Most of the crowd, however, congregated around the perimeter of the landing area.

Anyone who missed the competition could read about it on the front page of the Reformer. The Monday edition featured two large sets of headlines of equal size reporting the top stories. One stated that Cardinal Achille Ratti had been elected pope and had taken the papal name Pope Pius XI. The other story read: “National Amateur Ski Record Made Saturday on Brattleboro Jump.” A series of subheads included, “Crowd of 2,500 Sees Spectacular Winter Sports Event,” “New Jump Declared by Experts to Be Best They Ever Saw,” and “New England Record Smashed 11 Times.”

The paper noted that “R.E. Maxwell of Dartmouth Outing Club…held the New England record for a period of two or three minutes,” before it was bettered. Five different competitors each surpassed the former regional record. John Carleton won the day with a 150-foot “perfect leap” on his first effort.

Fred Harris chose not to compete, but jumped too, just for the thrill of it. He “gave a splendid exhibition of form in his jumps,” the Reformer wrote, “and he came in for a good share of the applause by the crowd. The onlookers, especially the Brattleboro residents, knew that but for him the ski jump project never would have come about.”

Michelson, the skier who arrived with a concussion, opted not to compete because of his injuries. The only reported injury that day was the one suffered by C.N. Proctor, a 17-year-old high school junior from Hanover. Having set a high school record on his first attempt, his second jump didn’t go as well. The strap on his right ski broke, “which let the ski assume a perpendicular position with the point downward, which spelled trouble in the minds of the spectators,” the Reformer wrote. “When Proctor landed the point of the ski struck first and the heel of the ski struck him in the back. He slid and rolled to the foot of the hill.”

After staying to watch the end of the competition, Michelson agreed to be examined at Brattleboro Memorial Hospital, where doctors found he had suffered a muscular injury between his shoulders, but nothing more.

Shortly after the event, Harris received a quirky anonymous letter. Under the heading “Anticipation,” the writer described the sorry event they had expected to witness: “Suspicious sky. …Delay in getting started—band frozen—cold feet—audience indulging in sarcasm—and getting impatient. Some leaving before the jump starts. Jump goes off well, a few falls, much ignorant criticism and very weak applause. Constant reference to money foolishly expended and cold feet.”

And under the heading “Realization,” the author then explained what they had actually experienced: “A wonderful day. Young, old, fat, lean, some in sleighs, some in cars, others on foot, all going one way. To the ski jump. …What a sight. A wonderful ski jump rising Heavenward. Throngs of enthusiastic spectators. The band starts, and all eyes turn toward the jump. A jumper appears at the top, the crowd watches tensely, the bugle call, and he is off. …He makes a flying leap into the air. The audience is spellbound. He whizzes through the air! (E)veryone holds their breath! (I)n perfect form he descends and lights gracefully 150 feet. A great sigh of relief from the spectators and then thundering applause. Man after man comes down, all brave, daring and wonderful. Then it is over. The crowd is sorry to go and linger(s) expectantly, hoping that there will be just one more jump. Everyone has had a thrill never to be forgotten. And over the babble of the excited conversation can be heard. ‘When is there going to be another one?’ ”

There have been plenty more. For more than a century, the Brattleboro hill has continued to host ski jumping competitions, including nine national championships and an Olympic qualifier. And ever since 1951, the facility has, fittingly, been known as the Harris Hill Ski Jump.