Listen to this article

On Saturday, with his wife and three kids in the car, Alexi found himself rapidly approaching the northern border of Vermont, a place he did not want to be.

In the following 30 hours, Alexi and his family, who are from Venezuela, would be detained by federal immigration officers despite having used legal pathways to live in Vermont, according to Alexi and an attorney working on his case. While his family has since been released, Alexi has been detained by ICE in a Vermont prison since Sunday night.

Advocates say the case is an example of a new landscape, brought on by the Trump Administration, in which people who aren’t citizens are being detained and arrested at an increasing pace, and for a broader set of reasons.

“This immigration detention certainly has the hallmarks of a shift under the new presidential administration,” said Will Lambek, with Migrant Justice, an advocacy group for immigrants.

Alexi was trying to go to Costco, he said, which is in Colchester. He missed the exit and lost cell service, which turned his GPS map into a blue dot on an otherwise blank screen.

“I kept driving, but I never thought I would make it all the way to Canada,” Alexi said.

It was one of the first times his family had ventured out of the house to buy groceries since Donald Trump took office, according to Brett Stokes, an attorney working on Alexi’s case, because the family was scared immigration officials might approach them.

Alexi asked VTDigger to identify him only by his nickname because he is concerned about retribution from immigration officials. He spoke to VTDigger from prison on Wednesday afternoon. His comments, spoken in Spanish, were translated by Lambek.

Alexi said he realized he was approaching the U.S. Customs and Border Protection station in Highgate, on the country’s northern border, and wanted to turn around, but there was no place to make the turn. When he tried, officers approached his car; his attorney later confirmed they were with U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

He used a translation app on his phone to say he was lost and explain he just wanted to turn around and go back where he came from, he said.

The officials told Alexi, his wife and three kids — ages 1, 4 and 7 — to follow them inside the border crossing station so the officers could check their documents, he said. Alexi estimates they were held overnight, from 3:30 p.m. on Saturday until after 9 p.m. on Sunday. Everyone, including the children, slept on the ground on mats, he said.

“That whole time, all we had was water and some crackers,” he said.

Ryan Brissette, a spokesperson for U.S. Customs and Border Protection in New England, said he would not be able to respond to VTDigger’s questions about the family’s detainment before publication.

Then, late on Sunday evening, officers — who spoke to the family through translator apps, according to Alexi — told the family that his wife and kids could go free, citing their Temporary Protected Status. They would be dropped off at a McDonalds 20 minutes down the road, Alexi recalled the officers telling him.

But Alexi was transferred to a Vermont prison to be held in detention. Records with the Vermont Department of Corrections show he was booked into prison late Sunday night.

“I responded, ‘No, you have it all wrong. I have a protection, too. I’m in process,’” Alexi recalled telling the officers.

A change in ‘policy and culture’

At 9:15 a.m. on Monday, Stokes, one of Alexi’s lawyers and director of the Center for Justice Reform Clinic at the Vermont Law and Graduate School, had just received the call about a family from Venezuela detained at Vermont’s northern border.

As one of the only attorneys in Vermont who represents noncitizens arrested by federal agents, Stokes is often one of the first people to get the call when such arrests take place.

As Stokes sorted through the details of the case, he understood that this arrest probably would not have taken place months earlier, under the Biden Administration.

Alexi and his family moved to the United States from Venezuela in 2023. They left Venezuela because of the political turmoil there, he said.

“If I were sent back, I would be detained immediately, because I’m considered to be a defector,” Alexi said.

While the entire family applied for Temporary Protected Status at the same time, Alexi’s application has not yet been approved. He does not have a criminal record, Stokes said. His wife and two of his children have Temporary Protected Status, and his youngest child, who will turn 2 years old next month, was born in the U.S. and is an American citizen, according to Alexi.

Temporary Protected Status, a designation granted by the Department of Homeland Security, gives people protections from deportation if a situation in their home country makes their return unsafe. People with the status, or “who are found preliminarily eligible for TPS upon initial review of their cases,” are not deportable, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. They can obtain employment authorization and can be granted travel authorization.

Alexi has been found to be preliminarily eligible, and “another level of review has happened in his case, such that” he was able to obtain a work permit, Stokes said.

On Feb. 1, 2025, Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem terminated Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelan nationals granted in 2023. But that decision, slated to take effect in April, shouldn’t impact this case, Stokes said.

“The fact of the matter is, (Alexi’s family has) two separate ways to demonstrate that they have permission to remain in the United States,” Stokes said — Temporary Protected Status and work authorization.

Had the family been questioned by immigration officials a few months ago, they probably would have been quickly let go, and the case never would have made it to Stokes’ desk, he said.

What transpired after immigration officials first made contact with Alexi’s family “shows a shift,” Stokes said. People with pending applications are coming into contact with immigration authorities, and rather than being let go, “they’re being detained, and putting these folks who already have processes in place into deportation proceedings,” he said.

Lambek, with Migrant Justice, agreed.

“We’ve seen people who have accidentally driven to the customs checkpoint before, and who haven’t been detained,” he said.

While it’s difficult to draw conclusions from a single case, it indicates a change in “policy and culture,” Lambek said.

‘Tamping down rumors’

Throughout the last few weeks, misinformation has spread widely in Vermont about the activities of federal immigration officials, and particularly Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

Community organizations, including the advocacy group Migrant Justice, have been inundated with tips and information about arrests, raids and federal officer sightings, much of which has proven unfounded, Lambek said.

What’s making its way to the organizations appears to be indicative of the misinformation that has reached immigrant communities in Vermont. That has created a fog of uncertainty about whether people who are not U.S. citizens are safe to go about their daily lives.

In one instance, workers in the hospitality industry heard a rumor about an ICE sighting at a supermarket, and “somehow that got shifted into, ‘There’s going to be an ICE raid,’” said Lambek. The workers all stayed home as a result.

In another instance, a worker who suffered an injury on a farm heard a rumor about ICE in Burlington while on his way to an urgent care appointment.

“He turned around and forewent medical attention,” Lambek said.

A big piece of Lambek’s job right now, he said, is “following reports” and “tamping down rumors” while also “trying to provide specific and timely information.”

“There definitely is an increase in ICE and Border Patrol activity. Some of that is leading to arrests. And then there’s a lot of noise around it that makes it difficult for people to know what to make of the moment,” he said.

ICE did not respond to VTDigger’s request for comment.

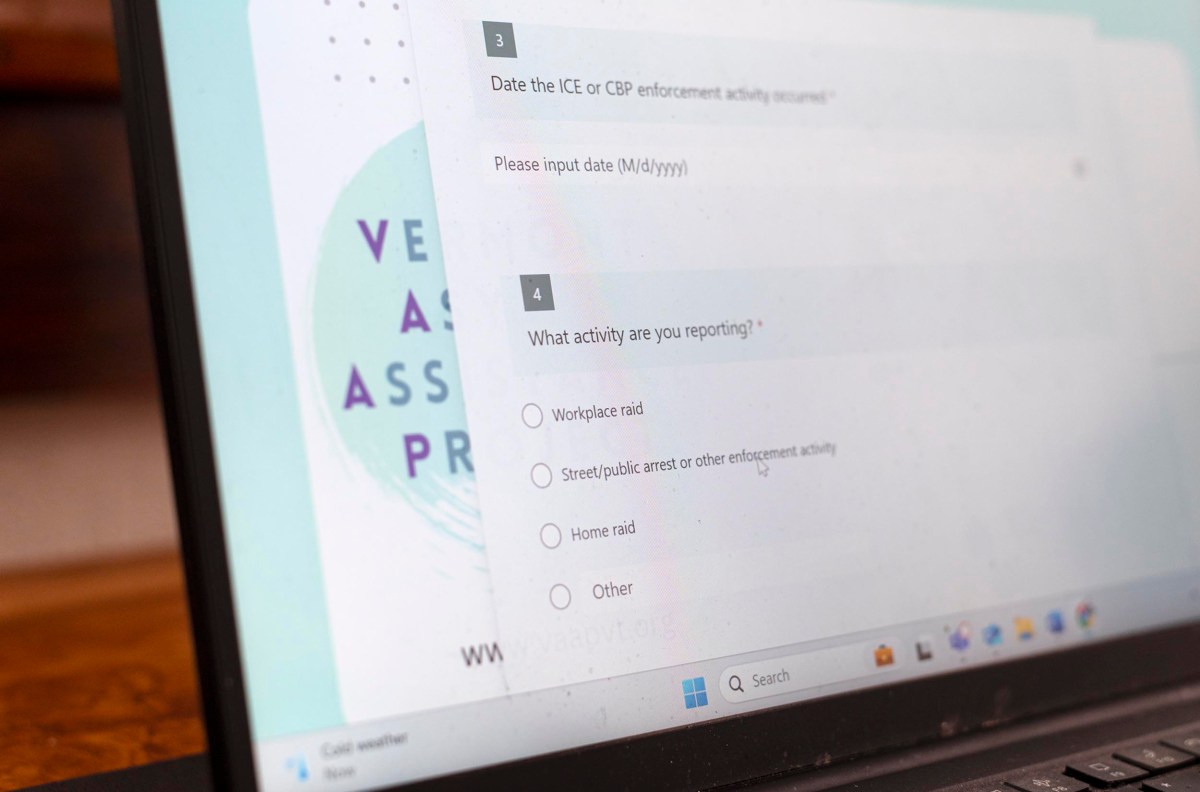

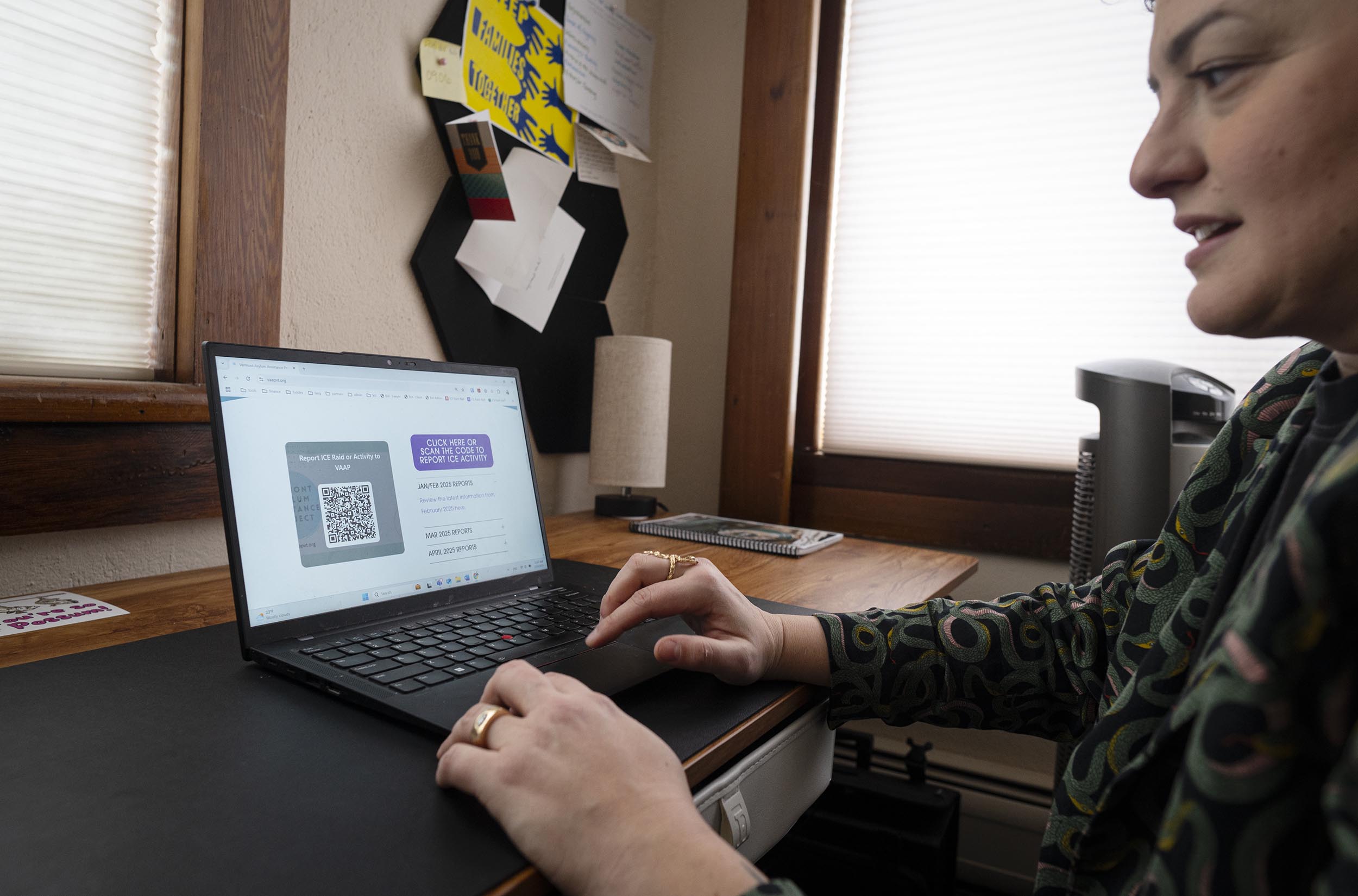

On Monday, as Stokes was looking into Alexi’s case, Jill Martin Diaz — the executive director of Vermont Asylum Assistance Project, which provides legal help to people seeking asylum — sat in the organization’s Burlington office and pulled up a webpage with its recently-launched ICE activity tracker tool.

The tracker, designed to set the record straight about what’s happening on the ground, has experienced its own deluge of misinformation.

It includes a form that anyone can use to log observed or experienced activities of federal immigration officials. Martin Diaz then publishes only the verifiable instances of ICE activity and enforcement for the public to see.

At first, Martin Diaz received a flood of tips and information. Some of it appeared to be submitted by people who disagreed with the organization’s advocacy work (“What were they doing? Hopefully sending them all back. It’s beautiful,” Martin Diaz said, reading aloud from the submissions). But, at first, some of it appeared credible — or at least submitted in good faith. And it was overwhelming.

“At first I was scared,” they said. “I was like, ‘Oh shit, this is crazy. It’s happening.’”

But then Martin Diaz stepped back, “as you have to do now, all the time, to catch yourself and to help catch everyone around you. Because I’ve seen really, really, really smart, experienced, seasoned people activate in response to misinformation.”

‘People are terrified’

Once Martin Diaz waded through “explicit anti-immigrant hate, bigoted hate,” “some sexist, homophobic stuff,” and some potentially well-intentioned but false information, the tracker proved to be a useful tool.

Martin Diaz was previously unaware of at least two detentions — one in Burlington and one in South Burlington — that other community groups reported to the tracker, and that they were able to verify.

As of Feb. 13, the organization posted nine reports of confirmed activity, including at least eight instances in which one or more people were detained in Vermont and one in which a person was detained in New York but transferred to a Vermont facility.

“I think people are terrified,” Martin Diaz said. “I’m hearing from service providers, social workers and other types of community workers, ‘My client doesn’t want to send their kid to school today. My client is afraid to drive their kid to the bus stop. My client missed her health appointment. I haven’t heard from my client in a few days.’”

According to observations of advocacy groups and attorneys representing noncitizens, the pace of ICE arrests had increased substantially by mid-February, but remained less than a dozen. Martin Diaz was not aware of any workplace raids.

Stokes’ clinic, which is “one of the only places in Vermont that was likely to receive a call for someone who’s actually been arrested and detained by immigration,” he said, received two calls about people facing those circumstances last year.

Since Jan. 20, the day Trump was inaugurated, he’s received four.

“In my point of view, there is an uptick, whether ever so slight or large, in enforcement actions,” Stokes said. “That’s for certain.”

Martin Diaz said pre-existing immigration laws related to deportation and detention “are now being implemented at a slightly more frequent pace than they have been historically in my years in Vermont. We’re seeing a couple of arrests per week, whereas, under Biden, it would be a couple of arrests per year.”

“We’re seeing arrests in error,” they said. “But that also happened under Biden. We’re seeing due process rights being abrogated. We also saw that under Biden. Just like, some of it’s not new, it’s just happening with more frequency.”

Federal immigration officials also appear to be more active, according to Martin Diaz. They’ve been spotted in the parking lots of grocery stores, department stores and banks, they said.

“The law has already said that they can just drive around and be menacing,” Martin Diaz said. “That’s always been the case. It seems like the administration, right now, is prioritizing resources on that: ‘Yeah, go drive around and be seen.’”

‘I have to be strong for them’

While ICE and the Vermont Department of Corrections have a contract to hold detainees in the immigration system for several days, Alexi is likely to be moved soon. Stokes said he’s not sure where he would go, but it’s possible he’d be transferred to an ICE facility in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Meanwhile, Stokes and other lawyers working with Alexi are making a case for his release, and Stokes said it’s possible, but unlikely, that would happen before he’s transferred.

Alexi said he and his family have been received “with open arms” in Vermont. He’s become involved with the organization Central Vermont Refugee Action Network, and found regular employment, he said.

“Everyone we’ve met has been so welcoming, and I’m so thankful,” Alexi said. “I don’t have a single complaint against anybody I’ve met in Vermont.”

Being held in the prison, with little idea of what might happen next in his case, is “really strenuous, mentally,” he said. “But I know I have to be strong for my family, because if I give in to depression, then my family would, too, so I know I have to be strong for them.”

Alexi said he doesn’t believe he should be in prison because he hasn’t committed any crime.

“I don’t think this is an appropriate place for me to be,” he said.