This story by Tommy Gardner was first published in The Stowe Reporter on Dec. 5

When it comes to providing drinking water to an ever-expanding populous, Stowe cannot simply go with the flow and hope its supply lasts forever.

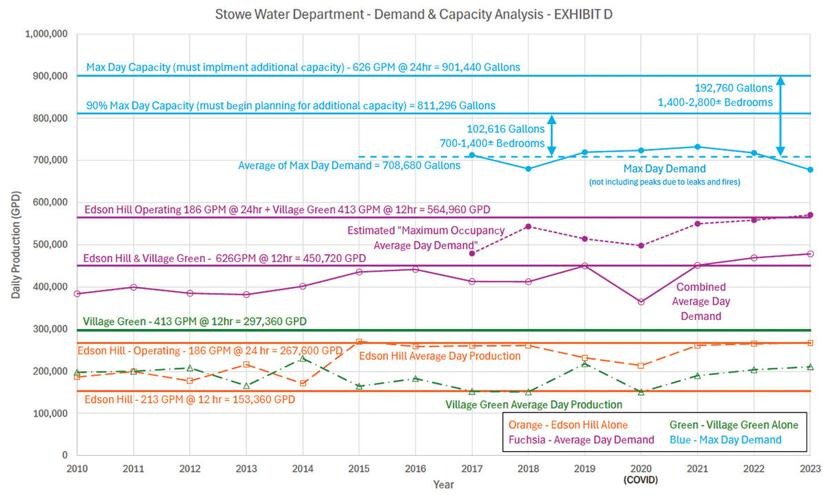

According to Stowe Public Works Director Harry Shepard, on the busiest times of the year — think peak foliage weekends or ski season holidays when tens of thousands of visitors flock to town — the amount of water being used is disconcertingly close to the system’s capacity. However, at most other times of the year, Stowe has water to spare.

“We are so seasonal,” Shepard told the Stowe Selectboard last week. “It really is incredible how different our demand profile is at different times of the year.”

The selectboard last week tasked the town staff with continuing its efforts to develop a new source or a new treatment strategy for its water supply, prioritizing conservation of what some day could be a more precious resource.

How long? About 1,500 bedrooms from now.

That’s Shepard’s rough estimate of how much more development the town can absorb before it needs to seriously consider boosting its water capacity.

Shepard last week presented a highly detailed summary of the town’s water and sewer capacity to the board. In it, he notes that “maximum occupancy average day demand” for water has been growing — minus the 2020 pandemic dip — by about 7 percent per year.

The town can handle that rate of growth, for now.

“I think if we progress from 7 percent a year, we will still be OK, but it’s something that has to be kept track of,” he said.

‘Most complicated’ system

According to Shepard’s report, Stowe gets its drinking water from two different sources.

One of them is on Edson Hill and draws from the same aquifer that lends its name to the nearby Robinson Springs neighborhood. It was built in 1924 — a century ago this year — and served Stoweites as their main water source for 75 years.

However, Shepard said there have been times when trying to pump too much from the Edson Hill source that peoples’ wells start to become noticeably depleted.

In the early 2000s, the second currently operating water supply facility was built near Cape Cod Road. Known as the Village Green water source, it can pump out 413 gallons per minute, twice that of the Edson Hill source.

Because of the large service area — all the way from Stowe village up Mountain Road to, and inclusive of, Stowe Mountain Resort — and the mountainous terrain, water from Village Green passes through five pumping stations and three water storage tanks to reach the most remote customers.

“We have a very complicated water distribution system, probably the most complicated in the state,” Shepard said.

Until recently, the Village Green had been eyed for future expansion. Complicating things is the discovery there in recent years of so-called “forever chemicals” that have been linked to ailments such as cancer.

So far, levels of these PFAS chemicals (scientifically identified as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) in the Village Green drinking water supply have remained below allowable levels, but that location is also one of the most bustling parts of town.

“It is also located in the Mountain Road Village zoning district, a growth center with commercial and residential uses and a golf course within its source protection area,” Shepard wrote. “This area is also experiencing other development growth pressures.”

Sewer stretched

When it comes to Stowe’s wastewater system, the limitations are more often pushed by what falls from the sky than by what gets flushed down peoples’ toilets.

This is particularly true for the Lower Village sewer pump station, located on the southern village outskirts. That station is roughly twice as old as the higher-performing sewer apparatus uphill of Weeks Hill Road, which was constructed in the early 2000s.

According to the report, the Lower Village station “performs admirably and within its design capacity” of 396,000 gallons per day during normal dry weather. But it gets severely taxed during heavy rains, like during this past July’s floods, when it pumped an estimated 847,000 gallons per day.

“Having those pumps run 24/7 for an extended period, even after the water level comes down, is not a healthy thing,” Shepard said.

The replacement of that pump station is on the town’s to-do list, with a current construction target timeline of 2027-2028. The current estimated price tag is $3-4 million.

“Modest growth over the next few years can be accommodated but risks of pump failure during these more frequent wet weather events will remain high until upgrades are implemented,” the report states.

Selectboard member Nick Donza said he cannot recall Shepard ever choosing not to recommend allowing wastewater allocations for new developments, but town manager Charles Safford said that’s normal. He said most developers listen to Shepard’s guidance, so they know what they need to do to get his seal of approval.

Even so, Shepard said that earlier this year he declined to recommend allocations for a new project, the 73-unit housing project proposed by Stowe Country Club off Cape Cod Road. It was the first time in his 15 years with the town, he said.

Josi Kytle, a member of Stowe’s recently formed housing task force, said water and sewer hookups are “big ticket items” for developers.

“This is constraining us to do any type of housing, affordable or mixed use or anything,” Kytle said.

Shepard said even though water and sewer customers largely shoulder the expenses for those utilities, upgrades to them are also big-ticket items. For instance, if the town was faced with PFAS treatment at the Village Green water source, it would cost $10 million to construct the infrastructure and $1 million a year to operate it.

“Everything in the water and sewer universe is extremely expensive,” he said.