EAST MONTPELIER — When Barbara and Roger Clark asked a logging company to harvest some of the trees on their roughly 80-acre property in 2013, they had no idea they would soon become the victims of a seemingly unpunishable crime.

Sitting at her dining room table with her son, Barbara Clark didn’t remember exactly how she found David, Paul and Joseph Codling, who operate a logging business in neighboring Plainfield. Roger was sick at the time and later died of cancer. Barbara remembers that Roger showed the Codlings which trees to cut — the ones with blue tape tied around their trunks — and then the couple, kept busy by Roger’s illness, left them largely to their work.

“We grew up in an era where your word was good,” she told VTDigger in an interview.

A Washington County civil court judge would later rule that the Codlings took far more timber than they’d promised. The loggers left piles of debris that took the Clarks two summers to clean, and freshly opened patches of sunlight gave invasive species new life.

While the Codlings took tens of thousands of dollars worth of timber, according to court documents, the Clarks never saw a dime. On June 15, 2016, Superior Court Judge Timothy Tomasi ordered the Codlings to pay the Clarks more than $240,000, with an annual interest rate of 12% on any unpaid balance.

But in timber theft cases in Vermont, court orders often don’t accomplish much. Almost eight years later, as of this month, the Codlings still hadn’t paid the Clarks.

In many states, such an unpaid fine would result in jail time, Rep. Marc Mihaly, D-East Calais, told lawmakers in the House Agriculture, Food Resilience and Forestry Committee earlier in this year’s legislative session. In Vermont, the state refers the fine to a collection agency, which sends a nasty but ignorable letter, according to Mihaly. Perpetrators of timber theft, he said, are “not unintelligent in their approach.”

Mihaly is one of the primary sponsors of H.614, the state’s latest attempt to put an end to the practice. The bill passed the Vermont House last month on a voice vote with little debate and is now under consideration in the Senate.

The bill would create a new category of crime for timber theft, called land improvement fraud, similar to home improvement fraud, which is already a crime. It would add land improvement fraud to the existing home improvement fraud registry, which publishes the names of people who have been convicted of either forms of fraud, making it easier for a landowner to search before accepting a logger’s services.

But on its journey through House committees, the bill has lost some of its teeth, including a provision that made it easier to seize the logging equipment owned by serial offenders. Without it, some question whether the proposed law would make an impact.

Reached by phone in February after the state Attorney General’s Office filed suit against the Codlings, alleging they had violated the state’s Consumer Protection Act, David Codling said he wasn’t aware of the $240,000 judgment against him from the Clarks’ lawsuit. “I never got a thing on paper, or from anybody, that that happened,” he said.

‘Everybody’s pissed’

The Clarks are not alone. Over the years, in the Statehouse, in the offices of the attorney general and Vermont Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation, and in at least one citizen group created for people who have experienced timber theft, Vermonters have told different versions of the same story.

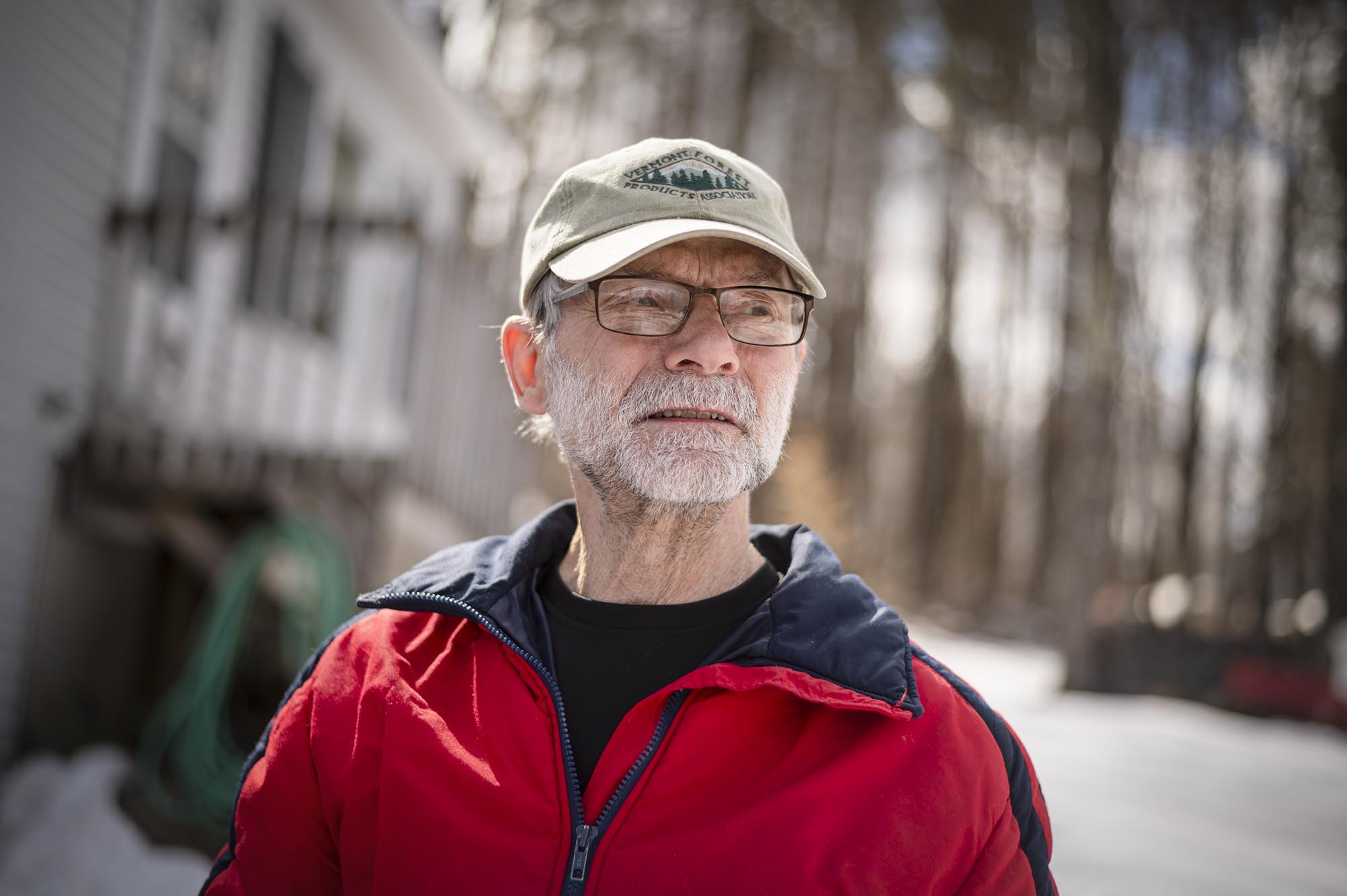

Michael Carriveau’s Plainfield home looks out on a hilly landscape dotted with ragged tree stumps of varying sizes. He, too, won a civil lawsuit against the Codlings, representing himself in Washington County court, after he said they took more trees than he had requested and left his property a mess in 2018.

In court, the “goal post was constantly shifting,” said Carriveau, who describes himself as a senior citizen and a veteran. The Codlings have never paid his judgments. By the time the judge asked whether he wanted to file a contempt of court charge, he’d had enough.

“I realized I was fighting a system that was doing nothing for me,” he said.

After that, Carriveau went looking for answers, finding two dozen other victims. Most did not go to court, he told lawmakers, “because it was well-known by the general population: Restitution was not, I repeat, not, going to be forthcoming.” He contacted state police and prosecutors, the Vermont Department of Forest and Recreation, a statewide forest industry group — and Mihaly.

“This is actually a problem I didn’t know anything about, until I was brought into a room with about a half-dozen very angry constituents,” Mihaly told lawmakers when the bill was first introduced in January.

A lot of the angry people are other loggers: The relatively tiny subset of the industry gives all of them a bad name, he said.

“It’s really amazing,” Mihaly said. “When you’re in the room, everybody’s pissed. Everybody’s frustrated at the inability to get at these guys.”

Judgment proof

Even when the state itself is a party to the court action, regulators have had trouble holding perpetrators accountable for their actions, and stopping them in the future.

In 2006, loggers Ken Bacon and Ken Bacon Jr. received permission to cross state land to access a job on a privately owned parcel, then repeatedly violated the rules and practices required for doing so, according to a 2010 Environmental Court decision on the matter issued by Judge Thomas Durkin.

They crossed several streams with logging equipment, causing sediment and debris to discharge into roughly 1,000 feet of stream length, according to the court decision. In one case, the loggers’ equipment “completely eliminated any discernible stream channel,” Durkin wrote.

The Bacons stopped appearing at visits the state requested and did not respond to notices of violation. Eventually, the property owner paid for the cost of remediating the site.

The court ordered the loggers to pay $11,751. But at that time, Ken Bacon had “already been subjected to compliance proceedings, enforcement litigation and fines for violations similar to those he and his son committed” on the state and private property, Durkin stated.

By 2017, the state had taken the Bacons to court for three different matters — and won each time. A contempt order required the loggers to “cease all logging business activity … in their personal or any business names.”

In the state’s case against the Bacons, Gary Kessler, formerly the director of the compliance and enforcement division of the Agency of Natural Resources, got permission from the court to seize logging equipment. Investigators from the Agency of Natural Resources worked with county sheriffs and law enforcement from the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. They located the machinery, then encountered a brick wall: The sheriffs would not move forward with the seizure.

The sheriffs cited a law that protects certain property, including equipment that a person uses to make a living, from being seized by the government, according to Kessler.

In January, Kessler sat before lawmakers in the House committee, urging them to pass a law with enough force to break the cycle of impunity.

“If somebody was a locksmith but also a thief, and you said, ‘we’re gonna seize your lock picking equipment,’ and they said, ‘wait, I use that for my job!’ — well, sure you do, but you also use it for something else. You know, it’s sort of the same situation here,” he told lawmakers.

He reflected on his yearslong efforts trying to make the Bacons and other rulebreakers comply.

“This issue is important to me, because when I was at ANR, this was something that we struggled with constantly,” Kessler said. He told them he had just seen a recent news broadcast that highlighted continued alleged violations and theft by the Bacon family, “the same people that we were prosecuting back when I was at ANR in 2010, 2011, 2012.”

By the time Kessler left the Agency of Natural Resources, the agency had not been successful at holding the loggers accountable or retrieving the state’s money.

“I would describe myself as relentless in trying to get the money that the state was owed after we got a judgment,” Kessler said, “but there are those people that are effectively judgment proof.”

The enforcement problem

Historically, timber theft in Vermont has often been treated as a breach of contract — a civil matter — though it can result in tens or hundreds of thousand dollars in damage to property owners. Sometimes, that’s money that older Vermonters are counting on to supplement a fixed income.

Earlier this year, Attorney General Charity Clark brought a civil lawsuit against the Codlings on the grounds of consumer fraud. If Clark’s office succeeds, each consumer could get up to $10,000, she said. Clark said the office can take measures to enforce potential judgments, but did not elaborate about what those enforcement actions could be.

Asked why she brought the lawsuit now, Clark, who assumed the role just more than a year ago, said that she brings lawsuits only after months of negotiations with a defendant — in this case, the Codlings — to try to reach a settlement.

“If we sue, our negotiations have failed,” she said.

Codling told VTDigger he’s received “paperwork” from the Vermont Attorney General’s office for “the last nine or ten years.” For that time, he’s ignored it. “I said, ‘I don’t know who you are,’” he said of the paperwork. “This could be a scam.”

Lawmakers have tried before to ramp up possible penalties for timber theft. In 2016, the Legislature made the act a criminal offense. However, the same issues of capacity that have plagued Vermont’s judicial system across the board have prevented that law from effectively addressing the problem.

Members of the Judiciary Committee interviewed a long list of people from Vermont’s law enforcement and judicial spheres — the commissioner of the Fish & Wildlife Department, sheriffs, police officers, state’s attorneys, representatives from the Attorney General’s Office — and heard the same answer: No one has the expertise or the capacity to prosecute or enforce cases of timber theft.

Partly, that’s because of something prosecutors have long said: They don’t have the resources to prosecute any but the most urgent criminal matters.

“We have 21,600 pending criminal matters in our court system right now,” Tim Lueders-Dumont, a deputy state’s attorney with the Vermont Department of State’s Attorneys and Sheriffs, told lawmakers in testimony about H.614. “They’re being handled by 58 deputy state’s attorneys and 14 state’s attorneys. We are in an absolute crisis of resources.”

Pressure has been mounting to focus on violent or more serious crime. Timber theft is also an area in which few, if any, prosecutors are experienced.

“We have experts in domestic violence, experts in drug prosecution, experts in homicide prosecution, unfortunately,” Lueders-Dumont told lawmakers. “The ones that aren’t bubbling up as much, sometimes they don’t have the same level of expertise, resources and training.”

Even if a party brings a case and wins against the loggers, no law enforcement agency has claimed the responsibility for holding the loggers to their judgments.

“We just don’t have the capacity to add a whole other area of enforcement to our portfolio,” Chris Herrick, commissioner of the Department of Fish & Wildlife, told lawmakers. Even if lawmakers allocated more funding for the effort, Herrick said he is “not sure that this lends itself to the typical fish and game law enforcement things that are a little more specialized.”

Presenting the bill on the House floor, Rep. Jed Lipsky, I-Stowe, himself a lifelong logger, said that “local police, sheriffs, state police, all have allowed that, in most cases, they lack the expertise, experience or resources to do these types of investigations.”

In contrast, states such as New Hampshire and Maine have dedicated forest rangers who work on issues including timber theft, and attorneys who understand how to prosecute the cases, according to Northern Woodlands.

‘A bunch of paper’

Among other measures to strengthen current law against timber theft, the original version of H.614 would have allowed the Attorney General or another law enforcement agency to seize equipment used in the theft.

But as with criminal prosecution, state officials have testified that they don’t have the resources to carry out such a seizure.

Kessler told lawmakers that the bill, H.614, would be most effective if it included the provision that allowed law enforcement to seize logging equipment.

Yet later, discussions in the House Judiciary Committee questioned the seizure section of the bill.

Was it lawful — or fair — to confiscate the equipment a person needs to make a living? How would the seizure help the victims? Where would the equipment be stored?

“I’m starting to increasingly feel uncomfortable that this isn’t fully baked, and I only mean the seizure and forfeiture part,” Rep. Martin LaLonde, D-South Burlington, chair of the House Judiciary Committee, told other lawmakers in late February.

Owen Ballinger, a lieutenant with the Vermont State Police, said that although the Department of Public Safety supports the bill, “we just don’t have the storage capability to seize skidders, trailers, large trucks and store them for any length of time.”

With Vermont’s constraints in mind, members of the House Judiciary Committee stripped the seizure and forfeiture section. Instead, they asked the Attorney General’s Office to study the issue, and report back to lawmakers next year.

Rep. Ela Chapin, D-East Montpelier, a judiciary committee member who presented the bill to lawmakers on the House floor last month, defended the bill as effective, even without the seizure component.

The legislation “is intended to give law enforcement and prosecutors more tools to capture more of this activity and hold people accountable,” Chapin said in an interview.

Other measures in H.614 would prohibit people who have been convicted of land improvement fraud from working for themselves or a relative. In order to earn money for logging, they would have to work for a company or person who does not have any fraud violations against them.

Finally, the person would need to either disclose their conviction to their new employer or post a $250,000 surety bond with the Attorney General’s Office. That provision would apply retroactively, so it would capture loggers including the Codlings and the Bacons who have outstanding unpaid judgments.

“What I see that we’re doing here is disabling them from making a living if they don’t follow through on what the court has ordered,” Chapin said. “And the other big thing we’re doing this session is trying to give the courts the resources they need to have capacity to do the workload that they have.”

But without the seizure component, Kessler told VTDigger he’s concerned that the bill isn’t truly enforceable.

“In the end, this is a bunch of paper, and if somebody just wants to ignore it, they will until somebody takes their equipment and they can’t log anymore,” he said.

For Carriveau, the loggers’ apparent impunity has represented a blatant systemic failure. He has a list of other researched solutions, some of which didn’t make it into the bill: requiring all loggers to have a license, for example, or requiring receipts from logging jobs, such as mill slips and trip tickets to be made available to landowners. But he’s happy to see the issue under lawmakers’ microscope.

Carriveau often sat in the House Agriculture Committee while lawmakers discussed the bill. Asked in an interview about how he felt about the fact that the measure was gaining traction, he said he felt “ecstatic.”

Clark, who is still owed a $240,000 judgment from the Codlings, talks with Carriveau often. She credited him with bringing the issue to the fore.

“There’s nothing we could do about it. Our hands were tied, really, until Michael started putting together things,” she said. “He’s fighting for this — he really is.”