This article by Aaron Calvin was first published in the News & Citizen on Dec. 7.

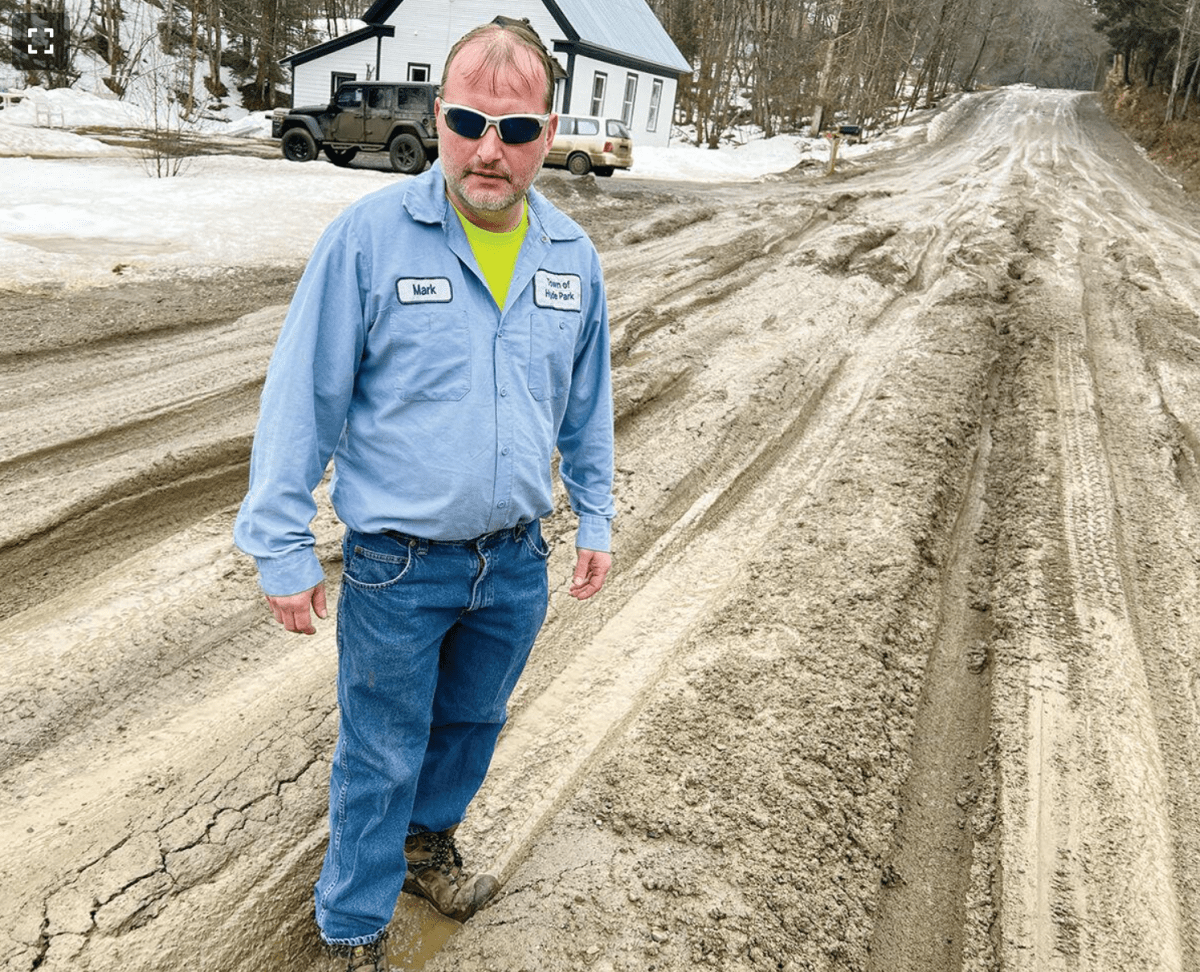

Hyde Park road foreman Mark French knows a thing or two about salt.

As a veteran of asphalt and gravel, and a caretaker of the vital stretch of blacktop known as Route 15 that spans from Danville to Winooski, he’s intimately familiar with the seasonal negotiation between vehicles and ice that takes place each long Vermont winter.

Salt is the necessary evil of cold weather road maintenance. It’s not great for the environment and it’s generally corrosive to cars, but without it, ice would form unchecked, leading to more collisions and crashes.

As in towns across Vermont and across the northern United States, French and his road crew spend most of their winter clearing and salting the roads to help facilitate safe travel, but when it comes to salt, he’s turned Hyde Park into Lamoille County’s test lab for using less salt more efficiently.

The solution is simple: water and salt, also known as a salt brine. If you ask French about it, he’ll extol the virtues of salt brine along with the finer points of its production and application in a thick North Country accent.

“When you combine salt and water, it’s immediately activated, and it takes the bounce back away, so it’s not all bouncing off the shoulder of the road,” French said. “We can actually cut our salt down because it’s all in the middle of the road, not scattered up to the ditches.”

It seems simple, but the process has required some commitment and belief that an upfront investment will pay off in future savings. So far, it has. Hyde Park purchased its own brine maker, and earlier this year used $45,000 in American Rescue Plan Act funds to upgrade it. The town saved over $10,000 alone in fiscal year 2023 in salt costs and cut its salt use nearly in half.

The town has also invested in thermal sensors on its trucks, which senses the temperature of the pavement, allowing the most efficient application of the salt brine on the roads.

“I think a lot of people look at the upfront costs, but look at what it will save you,” French said. “One storm, you can pay for it, so the second storm, you’re making money.”

Hyde Park is producing enough brine that the town has started supplying it to its neighbors, introducing them to its efficacy along the way, and legislators have called Hyde Park asking how to help implement the practice in their towns.

“It’s saved us around 30 percent of the rock salt usage over our traditional stuff, so we’re real happy with it,” Jason Whitehill, Johnson’s road foreman, said.

Cambridge only started applying brine late last winter, and road foreman Eric Boozan said he planned to monitor its application this winter before deciding on its use going forward.

Salt science

French has been effusive in his praise of the education initiatives being undertaken by Kris Stepenuck, an associate professor of watershed science, policy and education with the University of Vermont Lake Champlain Sea Grant and Extension program.

Salt brine has developed some negative connotations in some corners and taken on some difficult-to-dispel misconceptions. There’s some belief that it’s more corrosive to vehicles than traditional rock salt, and some think its name describes salt mixed with other chemicals.

It’s not that salt brine is less corrosive to vehicles and roads than traditional rock salt or that it’s better for the environment, said Stepenuck, but methods like those being used in Hyde Park means less salt is applied.

“What’s happening in communities that are using traditional methods is they might be putting out more salt, they might not be measuring it, and once the salt is in the environment, it’s there,” she said. “The less salt that we can put into the environment, the better off the environment is as a result, and also infrastructure.”

The temperature sensors play a large role. If the pavement temperature drops below 15 degrees Fahrenheit, salt can’t effectively prevent ice formation. By searching out patches where it’s warmer but still under the freezing point, road crews can apply the salt more effectively.

Rock salt eventually mixes with water on the pavement after it’s applied, but by prewetting it into brine, road crews ensure its adhesion.

Hyde Park may be leading the way with salt brine and evangelizing its neighbors along the way, but there are notable holdouts.

Stowe public works director Harry Shepard said his road crew continues to use rock salt and has experimented with some treated salt but hasn’t seriously considered switching to brine due to “concerns for both effectiveness of brine and capital investment for fleet conversion and storage to convert.”

Stepenuck said her research confirms that upfront costs have been the main barrier for towns in converting to salt brine. Brine machines can cost between $35,000 and $100,000.

“That is hard for communities to do if they don’t trust something,” she said. “It’s hard to make a commitment of that much money to try something out.”

Her solution to this issue would be for communities to pool resources or access grant funding to acquire regional brine machines that would allow them to try it out without assuming so much risk.

For Stepenuck, it’s the big picture of reducing salt use on roads and its effect on the environment that remains the overall goal.

“Salt has been used on the roads since the early 1940s, and what we know is that, back then, it was something like 5,000 tons per year, overall,” she said. “Now it’s something like 20 million metric tons, so there’s far, far, far more salt being put on the roads now than there was years ago, and it’s just doing damage over time, whether that’s getting into waterways or going into soils and contaminating groundwater.”