WINOOSKI — Samantha was working with her family at a restaurant in the city two Sundays ago when she overheard her brother talking about a shooting that injured three people in nearby Burlington.

At first, the 17-year-old thought it happened somewhere else in the United States — there are so many shootings in the news. So she tended to a customer before going back to the kitchen to ask about it.

That’s when she learned about the three young men of Palestinian descent shot and injured the night before, only a few miles from the restaurant and amid the ongoing Israel-Hamas war. As she does every day, two of the victims were wearing scarves symbolic of their religion and origin.

“I was shocked to hear it happened in Vermont,” she said. She read a news report, asked questions and wondered if she was safe.

Like other teenagers interviewed for this story, Samantha spoke under the condition of anonymity. She is using a pseudonym of her choosing in order to freely discuss the dread she has felt since that day, without fear of drawing the very attention she hopes to avoid.

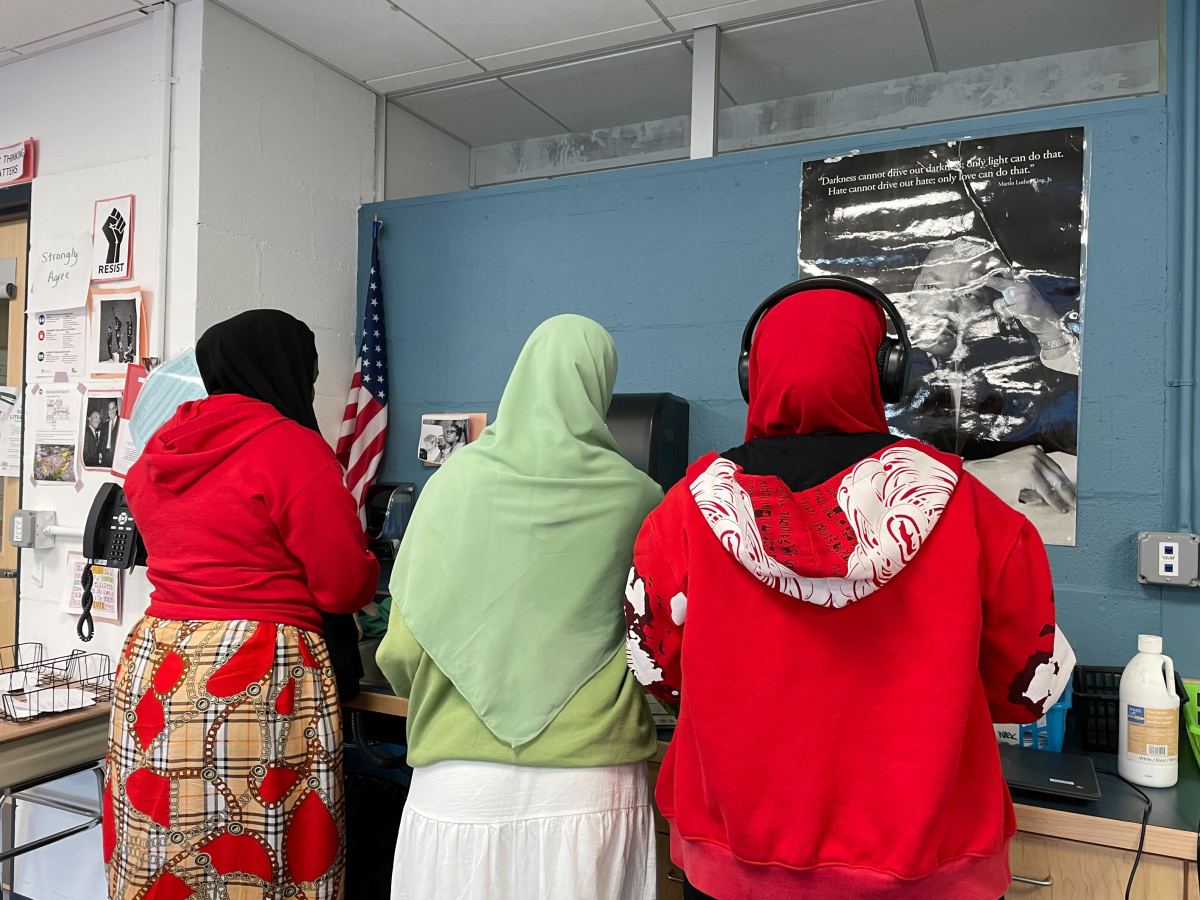

Wearing a long brown skirt and matching brown scarf that covered her head and neck, she was among four Muslim girls who gathered in a Winooski High School classroom last week to talk to a VTDigger reporter. The students, who all wore head coverings, shared their experiences since the shooting that drew national condemnation, including what the episode means to them and why they’re changing their behavior because of it.

Another student, Ifra, said she was working at a convenience store in Burlington when she got the news. Among her first thoughts, she said: “that must be a hate crime.”

She left work at 7 p.m. — it was quite dark — and said she was scared to walk outside. She read that the men shot were wearing headscarves. She was wearing one too.

“I’m Muslim and with the way things are in the world, anything could happen,” she said.

Faith leaders in Vermont share the same concern in the aftermath of an incident that has thrust Vermont in the global spotlight as the war rages in the Middle East.

Fuad Al-Amoody, vice president of the Islamic Society of Vermont, said last week he is particularly concerned for Muslim girls and women because their traditional clothing makes them stand out.

“I feel for them because if this continues and gets out of hand, the attacks across the United States, it’s going to impact them first,” he said.

The shooting happened Nov. 25 after 6:30 p.m. on North Prospect Street. The 20-year-old students — Hisham Awartani, Kinnan Abdalhamid and Tahseen Aliahmad — met at school in the West Bank and now attend American universities. Visiting Awartani’s family over the Thanksgiving holiday, they described walking through the neighborhood before they were approached by a white man who took out a pistol and opened fire.

Two of the three men were wearing keffiyehs, a traditional scarf that has become a symbol of Palestinian identity, and they were speaking a mix of English and Arabic at the time of the shooting, authorities have said.

Jason Eaton, 48, pleaded not guilty to three counts of attempted second-degree murder. No motive was discussed in Chittenden County Superior criminal court during his arraignment last week.

National and local groups have condemned the shooting and called on law enforcement to investigate it as a hate crime. Officials last week did not rule out the possibility if they uncover evidence to do so. Chittenden County State’s Attorney Sarah George, who has requested Eaton be held without bail, said at a press conference that the shooting was “a hateful act.”

In Winooski, home to Vermont’s most diverse school district in an otherwise predominantly white state, the four students said they always wear traditional clothing that include headdresses or scarves. They are of Somali descent but identify as Kenyan. They came to Vermont with their families through refugee resettlement programs from African countries.

Worried about what the shooting signals for local Muslims, Samantha last week texted the news article to her classmate and friend Sarah, 18, and told her to be careful.

“I was shocked because we never expected something like this to happen in Burlington,” said Sarah, who moved to Vermont with her family of eight at the end of 2015 and started school in Winooski in 2016. “My whole life here I was told that Vermont is one of the safest states in America.”

Her family initially lived in a small apartment in Colchester. She said it was near woods — remote and scary.

“I was shocked to see so many white people in one place,” she said.

As if on cue, an American flag perched on a tabletop suddenly fell over. The students laughed. One of them later put it back on its stand.

Since the shooting, their families in Winooski are worried, frequently checking up on them, asking them to be careful. In particular, the students said, their parents want them to limit their time outside for fear that they could be targeted in public.

That’s a problem for Samantha, who loves the outdoors and enjoys walks. She said she is sad she has to modify her behavior, but hopes to develop some indoor hobbies. She said she now tries to walk with someone else when she has to be outside.

Ifra and her twin, Sabrina, said their parents are scared. They moved with their family from Kenya to Arizona in 2016 through the refugee resettlement program, and then to Vermont in January 2017.

“That’s the first time I saw snow and it was dirty,” Ifra said with a laugh.

All four teens said they have generally felt safe in and around Winooski, which is why this incident feels unsettling. They are not sure how safe it is for Muslims in Vermont any more.

“It used to feel safe,” Sabrina said. “I feel safe in Winooski because I see other Muslims like me.”

Muslim adults make up less than 1 percent of Vermont’s population, according to the Pew Research Center. The second whitest state in the country after Maine, Vermont does not track demographic data by religious affiliation. Census data from 2021 shows that 1.5% of the state’s population is African American or Black and that foreign-born residents make up 4.4% of the population.

Winooski schools educate 76 refugee students and 231 English language learners. While 329 are white, there are 219 Black or African American students, 153 Asian and 36 multi-race students, according to data shared by the district. It does not track religious affiliations but administrators at the high school said they have several Muslim students, many of whom are refugees and wear traditional outfits that cover their heads, necks and bodies.

While there are other Black and Muslim students in school who wear traditional clothes, including hijabs, which cover a person’s chest and head, the students interviewed last week said they sometimes feel uncomfortable out in the community at large.

When she sometimes wears a “more modest” covering that shields her face, Samantha said people look at her “weirdly,” so she’s planning not to wear it in the wake of the shooting.

“It just isn’t safe any more,” she said.

Caitlin MacLeod-Bluver brought up the shooting up for discussion in her senior advisory the Monday after it happened because she believes it was important to acknowledge and process, she said. The group is made up of 12 fourth-year students, of which seven identify as Muslim, including the four girls who spoke to VTDigger.

“I knew that many students were going to need space to process what happened on Saturday,” MacLeod-Bluver said. “I wanted them to feel seen and valued, to know that they belong in our school and community, and to know that I stood with them against hate.”

She has also discussed the Israel-Hamas war with students and said she strives to “help students develop into active citizens and sense-makers of the world, empathetic listeners to others with diverse perspectives, and strong critical thinkers who can ask important questions.”

She acknowledged that, as a white person, she can’t understand the experiences of her students of color. But she said she tries to create the space for their full identities to be affirmed and for them to be comfortable about discussing everything.

Outside the advisory period, the students have not heard the shooting nor the ongoing conflict in the Middle East discussed in depth in any classroom settings, they said. If either subject comes up, they said, it is typically rushed or glossed over.

A couple of them said it is upsetting that world events like the war in the Middle East and ongoing conflicts in Africa are not discussed more.

“I wish the teachers talked about it as some students didn’t know what happened,” Ifra said. She said one other teacher asked her how she was doing before class last week.

Discussion of controversial subjects such as politics and religion is “strongly encouraged in the classroom because they add substance and relevance to learning and prepare our students to confront the challenges of their world today,” Miriam Greenfield, a spokesperson for the school district who sat in on the interview last week, said in an email.

Staff has been directed by the superintendent to discuss and provide an opportunity for students to reflect on the violence that took place in Burlington, Greenfield said. Some students might not be aware that those conversations are taking place.

“Teachers are asked to use state-adopted standards to structure these conversations and serve as facilitators of productive and respectful dialogue, setting boundaries (such as not questioning someone’s right to exist), and ensuring exposure to well-vetted, diverse, and high quality curricular resources,” she said.

Even beyond controversial topics, the four students said there is limited discussion about things not American. However, they have discussed World Cup Soccer and Eid, a major holiday celebrated by Muslims all over the world.

Winooski High School has for a few years held iftar, the fast-breaking meal during Ramadan, said MacLeod-Bluver, who helped organize it. Students brought home cooked meals and shared food with hundreds of students and staff.

The four students said they talked to their peers about the significance of fasting for Ramadan, the holy month during which observing Muslims fast from sunrise to sunset, and that there was a lot of interest.

They chatted about their impressions of Vermont around a table in the classroom — the snow, the cold, the layers of winter clothing — all things that felt strange to the new immigrants. A book from MacLeod-Bluver’s Grade 10 English reading list lay on the table: “All My Rage” by Pakistani-American author Sabaa Tahir.

Sarah said she loves summer in Vermont. It’s green, it’s warm and you don’t have to wear coats. The others nodded and commiserated with her about how hard their first winter in Vermont was and the long dark days ahead.