Gov. Phil Scott attended Barre City’s council meeting Tuesday alongside several top administration officials to unveil a massive redevelopment proposal for the north end of the city that was walloped during this summer’s catastrophic statewide flooding.

A sitting governor’s appearance before a local city council is not a typical occurrence. But the officials offered the plans, they said, to help the Granite City rebuild more resiliently — and be first in line to draw down federal funds, if they become available.

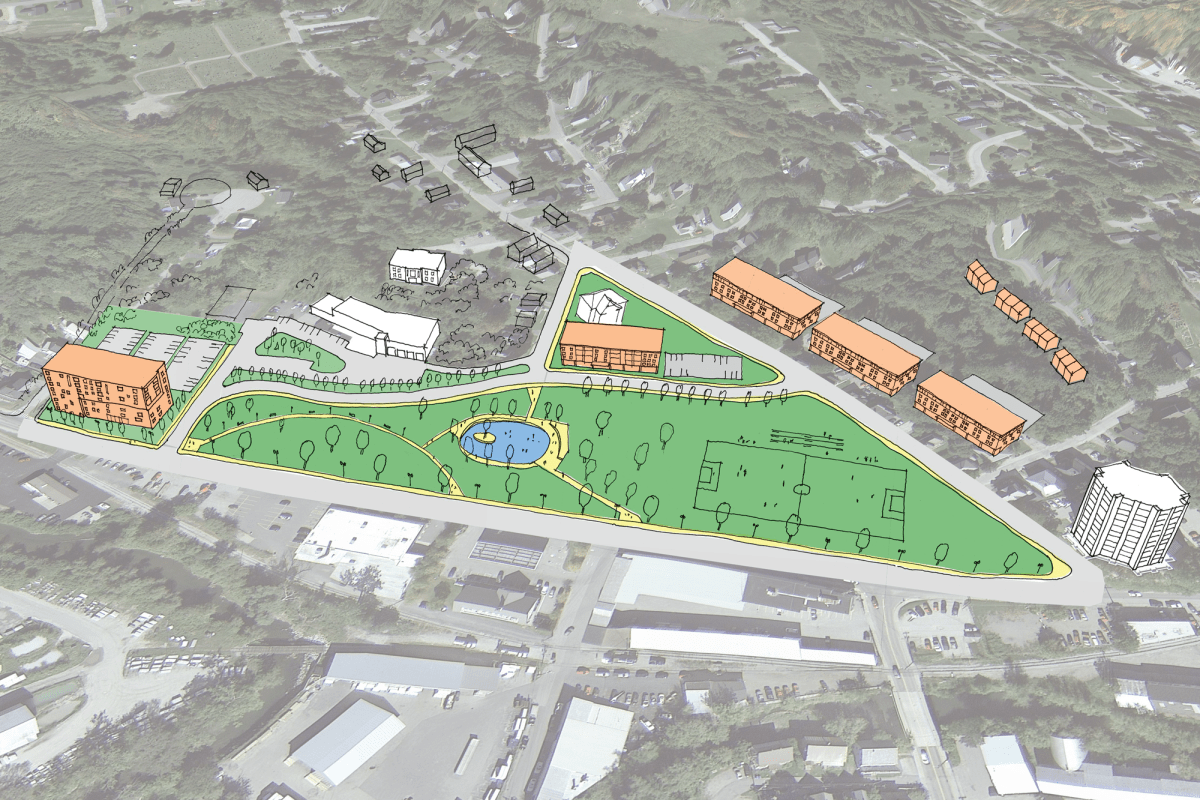

Drawings presented to the council, prepared by Montpelier architecture firm Black River Design at the direction of Scott’s office, reveal a completely transformed north end neighborhood. Officials envision demolishing most homes and apartment buildings along a five-block stretch from the intersection of North Main and Beckley streets to Fifth Street — which saw heavy flooding in July — to make way for a large park.

A mix of new housing construction, including high-rise and mid-rise buildings and single-family homes, would be built on the new park’s outskirts, including an eight-story, 80-unit residential building between Fifth and Sixth streets. If fully realized, the proposal would remove 92 existing housing units and replace them with 225 new homes and apartments.

State officials appeared cognizant of how unusual it was for the state to come before a municipality to offer such plans, emphasizing that their ideas were intended as a rough first draft — and would not be imposed from on high.

“This is not etched in stone,” Scott told the council. “This is a concept — a vision for what I see could be helpful to the city of Barre and to the region.”

Doug Farnham, whom Scott has appointed to lead the state’s recovery efforts, stressed that while the state was eager to kickstart planning, it would take its cues from local leaders and the community.

“We want to respect your local visions for growth,” he said. “Again, we’re bringing these sketches as a starting point for a discussion.”

Farnham also stated repeatedly that to assemble the property necessary to undertake the project, the state would not take homes against anyone’s will.

“We’re not going to be forcing this on anyone. The buyouts will be voluntary,” he said.

The governor, who grew up in Barre, and his administration have begun referring to the Granite City as ground zero for July’s floods. While many Vermont communities saw immense damage, the wreckage in Barre City stands apart, they say. The state picked up 4,000 tons of debris from Barre in the weeks following the floods — more than two-and-half times what it collected in neighboring Montpelier, Farnham told the city council in another meeting earlier this month. About 16% of all Federal Emergency Management Agency individual assistance claims in the state have been paid out to Barre residents, he said, representing a “very, very heavy concentration.”

“We always look back and compare the event to Irene,” Farnham said, referring to the 2011 tropical storm. “And if you do, you don’t find such a dense concentration of damage in Irene that we did this time around.”

Administration officials also pointed to congressional timelines to explain the speed and scale of their proposal. Scott described speaking to U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., at an event they both attended last week, when the senator “said there’s some opportunity in Washington right now,” Scott said.

“There is extra money that is put into the disaster relief fund that is going to be up for grabs, so to speak,” Scott said. “But there’s nothing that is being appropriated, individually or spread throughout the states. It’s first come first serve. So we need to act quickly. And so I took that to heart.”

But in response to questions from Barre City councilor Teddy Waszazak, Scott clarified some of the funds the administration was eyeing would require additional congressional approval. Waszazak replied that this made him “nervous,” and noted that, at the time, the U.S. House was in such disarray that it still lacked a speaker.

“I agree that we definitely need to have federal money to do whatever it is we’re going to do with the north end. But is there any — when the legislature reconvenes in January, is the administration going to propose any direct aid from state dollars to the city to help get things started?” Waszazak asked.

Scott replied that he and his team were “very hopeful in talking with our congressional delegation” that federal funds could cover the bulk of such a project.

“That’s our goal, without having to dip into local resources in any large-scale capacity, or into state funds either. But time will tell,” he said.

In an interview after the meeting, Farnham said that while the supplemental FEMA budget approved by Congress when it narrowly averted a government shutdown in late September should provide more money for Vermont to undertake buyouts, the project would require far more to actually develop the area. In particular, the administration is contemplating using Community Development Block Grants, he said, if additional funding comes through in Congress’ next spending bill.

The federal dollars Vermont seeks will have to make their way through a divided Congress, where, on Wednesday, Republicans in the U.S. House finally elected a new speaker: Rep. Mike Johnson, R-Louisiana, a hard-line conservative who led efforts to overturn the 2020 election.

But Vermont’s congressional delegation has also had trouble getting its own party to give Vermont much special consideration thus far. Despite letters and in-person appeals from Sanders, Biden omitted a laundry list of the delegation’s state-specific flood recovery requests from his supplemental budget request for FEMA earlier this summer.

Sanders’ office did not make anyone available for an interview to discuss the federal funding they believed might be available. Instead, a spokesperson for his office provided a written statement from his state director, Kathryn Van Haste, stating that Sanders had “fought hard to bring every possible federal resource into our state to aid our people, town, and state as a whole.”

“As Vermont moves from response to recovery and rebuilding, Senator Sanders is working closely with Governor Scott, the Biden Administration, and others to make sure impacted communities like Barre, Montpelier, Johnson, Weston and many more can determine how they want to rebuild stronger than before, as quickly as possible,” she said.

City councilors repeatedly thanked Scott for taking such an interest in the Granite City’s recovery. But they also peppered him and his deputies with questions about community engagement.

One resident, Joellen Calderara, underscored the point when, speaking from the audience, she remarked that one proposed multi-unit building was cited where her house currently stands. The drawings, she said, were “a little bit shocking for me to see.”

“I will tell you, for the people that are on First, Second or Third street — they’re more prepared to see something like this. But the homes on Beckley street that only had basement water are going to be shocked to see this,” she said.

Administration officials replied that community input and buy-in were indeed imperative. But the conversation had to start somewhere, they argued.

“I honestly feel like it would have been inappropriate for us to start directly engaging with the citizens in the neighborhood before talking to city leadership,” Farnham said. “So that’s one reason that we didn’t directly engage with the people, because I think that would probably freak them out.”