In our town, the library happens to be across the street from my house in a historic building that used to be the town hall. Bookshelves line the library walls, and other shelves protrude toward the center of the room, where soft couches and chairs allow for meetings and reading.

In a back room, there are toys for children. There is access to material online. There are DVDs. There is access to books by interlibrary loan, which means that the collections of scores of libraries throughout Vermont are available to readers.

These reflections on the importance of libraries come in the wake of the baffling, obdurate and shortsighted decision of Vermont State University (Castleton, Johnson, Lyndon, and Vermont Technical College) to close their libraries. The closings would eliminate seven full-time jobs and three part-time jobs, a savings that seems pitifully small in view of the cost. According to the reporting so far, the decision was based in part on a survey of a small number of students.

My town, Salisbury, has a population of about 1,200 people. There are never more than a few at the library at a given time. During my years at a university with about 14,000 students, the library occupied a seven-story building in the center of the campus. There was never more than a small percentage of the student body in that building at the same time.

But in Salisbury, as at the university, the libraries have been a physical focus of the reality of books, of learning, of the work of study.

In Salisbury, the librarian, or a diligent young man who sometimes subs for her, are there three days a week. There are programs for kids and gatherings for adults. Santa Claus appears before Christmas. The librarian, Ruth Bernstein, works hard to get people the books and other materials they need. Without the library, people could go on Amazon. They could wander the trackless reaches of the Internet. But they couldn’t drop by the library to talk to Ruth, who often has ideas about interesting books or takes in your ideas about books she might acquire.

I still remember my experience in the library at the university where I studied. More often than not there was a particular graduate student with unruly hair and a bushy mustache stationed at the entrance to monitor the comings and goings of students. I didn’t know who he was, but I remember his presence. I remember the reading room where a couple of dozen tables were arrayed, crowded with students in the evening, less so in the day. Academics were not all that was on their minds as they cast glances at one another, but most were at least trying to read.

I majored in English and still remember the experience of patrolling the stacks on one of the upper floors where I was presented with the vast realm of literary criticism and history that gave me a glimpse of the scope of a world that reached from Chaucer to Joyce. Actual books on the shelf made a statement that links on the Internet never have done.

Casting the students of today into the virtual world of texts floating on their computer screens without linking them to the world of actual books, even those they will never read, is to allow education to continue its decline into a dry husk.

I’m of the older generation, and this complaint may be dismissed as the whining of someone not attuned to the wave of the future. I have many such complaints. Look what has happened to newspapers.

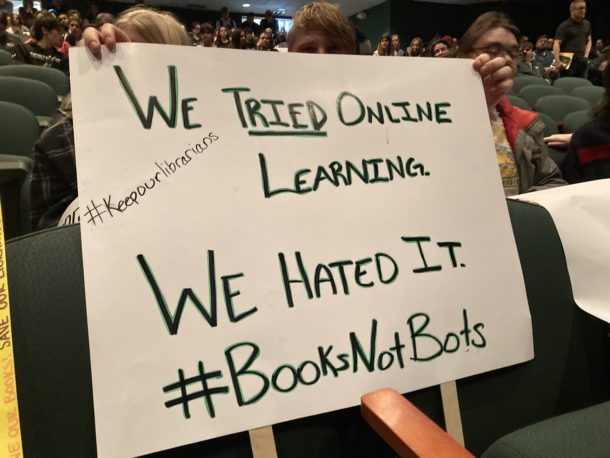

But the students who have protested the closing of the libraries are not truculent boomers. They are students who like to read, and reading is enhanced by the reality of the printed page.

In my own experience, I am often tempted to dive into a long story from The New York Times when I encounter it in the actual paper. It may well be a story I have passed over when I saw it online.

The same goes for books, which on the screen appear as part of a universe of endless text, but bound within hard covers are a singular, graspable expression of knowledge. I wouldn’t read a tenth of the books I read if I had to read them online.

Eliminating the chance to make use of the libraries would be an insult to the students. Instead, active librarians look for ways to highlight their collections, make use of their space, reach out and serve.

It would seem the point of the university, faced with present conditions of social fragmentation and diffuse online information, should be to bring people together as a community of learning, and that means together physically, in the presence of other students and books and teachers. Why even attend the university if everything is online?

The pandemic showed how lack of physical proximity sucks the life out of education. If you have given up on books, you have given up on education. That may be an old-fashioned idea, but so is the idea of education itself.