Burlington beaches reopened Monday afternoon after being closed for about 24 hours due to cyanobacteria blooms.

This is the second such closure this year, according to Erin Moreau, Burlington’s waterfront superintendent and harbormaster.

During the summer season, the city Department of Parks and Recreation conducts visual tests at city beaches for cyanobacteria daily and tests for E.coli biweekly.

Officials closed the Oakledge, Leddy, Texaco and North beaches Sunday afternoon after visual reports and water tests confirmed the presence of cyanotoxins in parts of Lake Champlain. All the beaches have since reopened after water testing today.

“I live in Burlington and I bring my kids to the beaches so we’re very conservative with what it takes for us to close the beach,” Moreau said. “We don’t want to take any chances — not only for our human population but we also know that it can really affect dogs.”

Common in lakes, ponds and rivers, cyanobacteria are “tiny microorganisms that learned how to photosynthesize” that often produce toxins harmful to humans and animals, said Lori Fisher, executive director of the Lake Champlain Committee, which runs a cyanobacteria monitoring program.

“So they helped create that oxygenated atmosphere on Earth making it hospitable to human life. It’s important to keep them in context and to know that they are native, they’re common, they’re a vital part of the ecosystem,” she said.

Often appearing as green or blue-green surface scum, not every bloom releases toxins, which can only be confirmed with lab testing.

“Some very small blooms can have a high amount of cyanotoxins in them and some very large blooms can have low amounts, so you can’t tell by looking at it. So when in doubt, stay out,” Fisher advised.

While cyanobacteria can grow in a whole range of different environments from very hot and dry to low moisture and cold conditions, officials say that climate change and warming waters seem to have exacerbated the blooms in recent years.

Blooms occur “when our beach waters are warmer and we start seeing the air temperature increasing and the wind decreasing,” Moreau said.

Cyanobacteria tend to thrive in water that has high amounts of nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen. It can make the water appear dark green like pea soup or spilled paint. Blooms can also appear white, brown, red or purple, according to the Vermont Department of Health.

Data from the past couple of years indicate that Burlington typically sees the blooms beginning in mid-July. Last year, according to Moreau, the city recorded blooms on July 12, 15, 20 and 22. They can be confined to a single day or can linger in consistently hot weather. A drop in evening temperature often helps clear up the blooms.

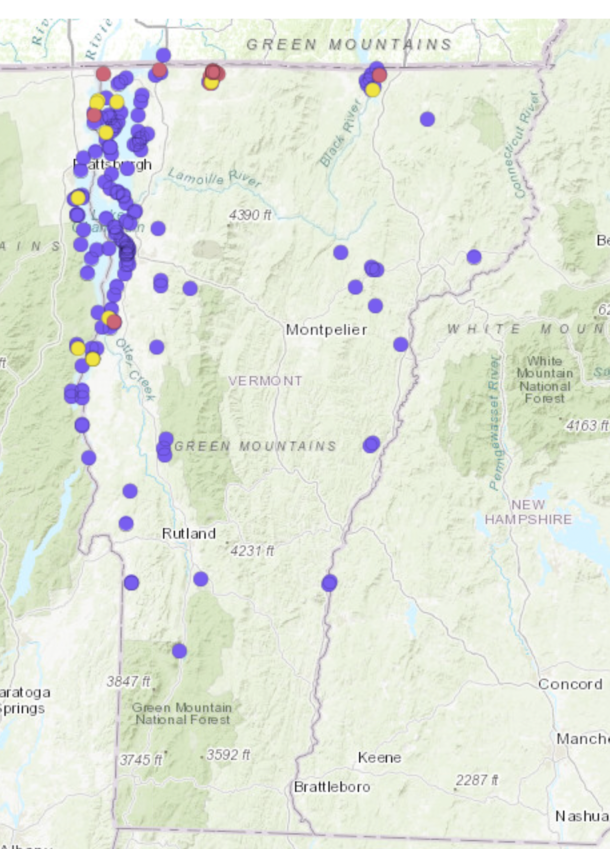

“We’ve definitely seen it go into September,” Fisher said, adding that it’s a concern in bodies of water statewide.

Cyanobacteria can produce any or a combination of hepatotoxins (affecting the liver), neurotoxins (affecting the nervous system) or dermatoxins (affecting the skin), and effects of exposure can range from headaches, coughs, rashes and stomach aches to liver inflammation and respiratory paralysis. Microcystis, a liver toxin, is the one most commonly found in Lake Champlain, according to Fisher.

Young children and dogs are most vulnerable as they can’t read signs, are often attracted to the smell and scum and are in danger of swimming in and ingesting the toxins. Officials have urged members of the public to report potentially hazardous blooms if they see any.

“We want people to learn how to recognize and avoid cyanobacteria and also report it so we can help keep everybody safe and take actions to help reduce the triggers for blooms,” Fisher said.