Vermont erupted into religious fervor during the early 19th century. Chalk it up to the weather.

Historians link the rekindling of Vermonters’ faith — in some cases their newfound faith — in part to a fluky run of truly awful weather.

The year 1816 brought the worst weather in the state’s recorded history. Heat waves alternated with unseasonable cold snaps. It snowed in June and frost hit twice in July. Crops suffered badly. There’s a reason people started calling the year “eighteen hundred and froze to death.”

The weather was almost biblical in its intensity. Some Vermonters attributed the drastic change in the weather to God’s wrath. They believed that the Millennium, the return of Christ to Earth, was at hand.

They didn’t realize that the weather change had been sparked by the dozens of cubic miles of debris shot into the atmosphere by a volcanic eruption halfway around the world, in what is today Indonesia. To religious Vermonters, and to some until-recently-not-so-religious Vermonters, this was a sign they needed to shape up.

In truth, the religious revolution that was about to sweep Vermont might have happened anyway. The latest war with England, the War of 1812, had just been concluded with a peace treaty. With the arrival of peace, the American people began to turn inward and consider loftier matters than politics.

Many Americans decided, upon reflection, that their countrymen had lost their moral sense. As a historian of the Freewill Baptists wrote, “the war had so relaxed the moral energies of even Christian men that profanity, Sabbath breaking, intemperance, and a general dissoluteness of life and manners, were becoming fearfully prevalent.”

Evangelical preachers set out to fan the dying embers of religious faith. Soon, Vermonters were aflame with belief.

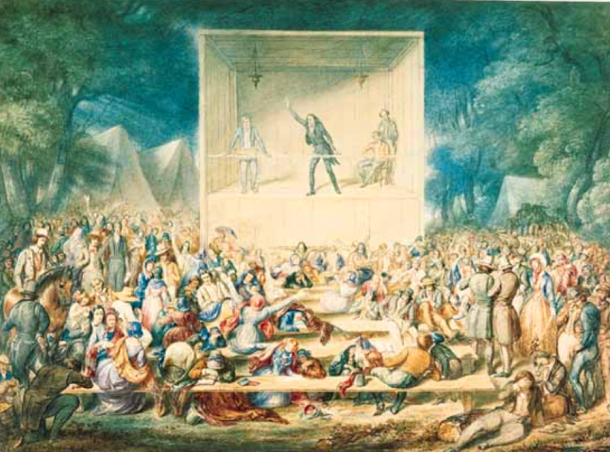

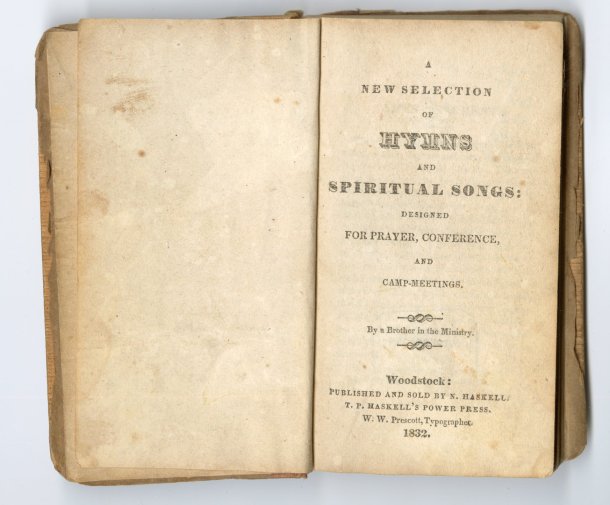

The efforts started locally, as Vermont clergymen preached in their own towns and neighboring communities. By the 1830s, Vermonters were hiring charismatic evangelists from out of state to preach before large crowds.

In preparation for the coming of a renowned preacher, communities would hold special prayer meetings over the course of two or three weeks. They counted on the visiting preacher to seal the deal.

During revivals, preachers would often set aside the front pews to serve as the “anxious bench.” These seats were reserved for people who felt they might be on the edge of becoming “born again” by giving up their wicked ways and accepting Christ as their savior, but who couldn’t quite commit. As they prayed at the bench, the preacher, members of the congregation, family and friends would pray for them by name and beseech them to convert.

An era of cooperation

The time was ripe for change. Religious strife had been growing in the country. Until recently, Congregationalist toughs had physically attacked Methodist preachers, and Universalists were widely condemned as atheists.

The revival brought unprecedented cooperation between denominations. They were still competing for souls, but now it was a friendly competition.

“This church and people have for a long time … made divisions among us which in a few months have vanished into thin air,” Hazen Merrill of Peacham reported in an 1831 letter to his brother Samuel, who had moved to Indiana. Religion was suddenly “the all engrossing subject,” he reported. “…Most of the town has had protracted meetings continuing four or five days conducted something after the manner of Camp meetings which have been the commencement of powerful revivals of religion. We had a meeting of this discription (sic) the 2nd week in July which seemed to produce wonders. …(S)o general is the work that there is hardly a person among us who does (not) feel anxious to share in its benefits — our old minister sees a day which he dared not to hope for.”

Indeed, by the mid-1830s, the state was vastly different from how it was only two decades earlier. During that time, Vermont had gone from a state that some observers considered morally lax to one in which fully 80 percent of the people attended church regularly.

As one historian put it, Vermonters were at the time “the most churchgoing people in the Protestant world.”

Not all churchgoing Vermonters were equal, however. To earn full membership in an evangelical denomination — the Baptists, Free Will Baptists, Methodists and Presbyterians — one had to declare oneself “born again” before the congregation. The nonevangelical faiths — Congregationalists, Episcopalians, Unitarians and Universalists — simply required that one support the church financially.

Church members in general and full members in particular enjoyed greater social status and economic success than did others. Members of congregations tended to stick together, hiring each other and lending one another money. The system worked well for church members — and might have encouraged some calculating people to claim faith they didn’t possess — but it shut out other Vermonters, some of whom chose to leave the state as a result.

If the growing importance of religion in Vermont left some feeling powerless, it also empowered a large and previous neglected section of society. Roughly 60 percent of Vermont churchgoers were women. Though many churches kept rules that allowed only men to vote on issues of church policy or select a new minister, some congregations granted women the right to vote.

Women increasingly took roles in the major social movements of the day, including abolitionism, and prison and educational reform, which became extensions of the religious revival. Their greatest success may have been the battle against alcohol abuse. By promoting temperance, women helped reduce the amount of alcohol consumed by Americans by two-thirds during that period.

The revival helped strengthen many marriages by encouraging men and women to view their unions as a sacred bond. Reducing drunkenness didn’t hurt either. Men, and occasionally women, who drank less were less likely to abuse their spouse physically or verbally.

Some couldn’t measure up

At the same time, noted Randolph Roth, a social historian at Ohio State, this new emphasis on people’s perfectibility put pressure on those who could not measure up. As the status of women increased, some men saw their status decline. And they snapped. During the 1830s and ’40s, northern New England suffered a 10-fold increase in wife murders, Roth found.

The revival of the early 1800s was eventually a victim of its own success. Churches had started the century as small institutions, so their members saw themselves as part of a select group that believed in people’s fallibility. The moral transgressions that drew their attention were, according to Roth, “interpersonal sins: gossip, slander, and fraudulent dealings in economic relations.” Recognizing human frailty, church members dealt humbly with those they considered sinners, offering them time to redeem themselves.

The religious revival of the following decades changed that. Increasingly the sins that church members attacked were drunkenness, breaking the Sabbath and skipping church services. People began to show less mercy to the morally backsliding. Church members openly gossiped about sinners. Since churches were no longer sparsely attended, congregations now felt free to expel members who committed transgressions.

Ultimately, the old elite who controlled the various denominations ended the revival, which they feared had become so raucous that it might impede their own salvation. These “respectable” people urged their clergymen to tamp down the emotion and populism that had fed the revival, and which had proved too successful for their own taste.