Weary at the thought of a third year of the Covid-19 pandemic? Consider the lives of the late Elaine and Robert Ransom, a Vermont couple from an era before cellphones and computers.

On Oct. 24, 1942, an 18-year-old Elaine waved her future husband off to World War II with the promise they would write to each other at least twice daily until he returned to their hometown of Rutland.

“Oh, darling, when that train started to pull out it was just as if someone was tearing my heart out of me,” she wrote in a letter that day. “When your face was out of sight, I will admit I began to cry … I still feel as if the bottom fell out of my world and I’ll always feel that way until you come home.”

Elaine and Bob’s correspondence is a reminder of simpler yet scarier times. Take the cursive penmanship in blue ink from a bottle. The single 6-cent airmail stamps. The faraway postmarks with the words “Passed by U.S. Army Examiner” — an intrusive assurance from federal officials who read everything soldiers wrote out of concern that “Loose Lips Sink Ships.”

The letters tell of growing up during the Great Depression of the 1930s, only to graduate to four years of sacrifice and shortages from 1941 to 1945 — for the women manning the World War II home front and their husbands, fathers and brothers keeping house in military tents and trenches overseas.

“Oh, how I wish I was all alone in a little soundproof room where I could talk out loud as I write to you, darling, and also let out a good cry that I am holding back,” Bob wrote April 16, 1944, from an Army base he wasn’t allowed to disclose. “Some of the boys are asking me how I can write so much and I told them if they felt as sad and blue as I do they could do it, too.”

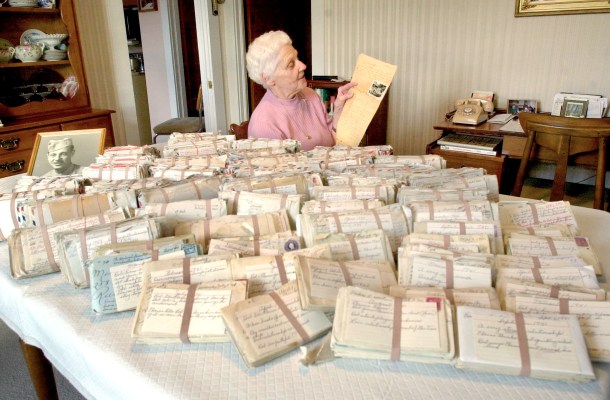

Elaine and Bob wrote to each other faithfully for three years until their reunion upon the war’s end, then bequeathed the resulting 4,000 letters to the Vermont Historical Society upon the start of the new millennium.

“It’s probably the largest single collection I’ve ever seen,” Andrew Carroll, the historian behind the best-selling book and PBS documentary “War Letters,” told Elaine during a 2005 visit.

Adding to its uniqueness is the fact that Bob — one of 49,942 Vermonters who fought in the war — found a way to save everything his wife mailed him while he was stationed in Massachusetts, Kentucky, Alabama, the West Coast and, ultimately, the Pacific more than 5,000 miles away.

“In any war zone,” Carroll said, “it’s very hard to hold on to letters.”

Such a stash is even rarer in a Snapchat society that deletes messages as soon as they’re read. Collectively, Elaine and Bob’s correspondence tells an epic story that puts the challenge of today’s pandemic precautions and supply-chain slowdowns into humbling perspective.

‘I was never concerned about this war before’

When Elaine Spencer and Bob Ransom first met as youth in 1939, Germany was invading Europe as well as front pages around the globe. But Elaine and Bob considered their biggest battles to be schoolwork and farm chores.

World War II did not touch most Americans until Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii Dec. 7, 1941. Elaine, for her part, didn’t feel it until she was a high school senior a year later. That’s when her boyfriend Bob, then 21, received a draft notice.

“Having submitted yourself to a local board composed of your neighbors for the purpose of determining your ability for training and service in the armed forces of the United States, you are hereby notified that you have been selected for training and service in the Army,” it read.

Elaine wanted to pretend Bob was simply going off to college. But as she wrote to him from study hall, she knew he would be living history, not learning it.

“Your going away would be OK for all but three things,” she wrote him Oct. 6, 1942. “One is I am afraid you will find someone else. The second is I am afraid something will happen to you. The third is that I am going to be terribly lonesome without you.”

“Darling, you know I was never concerned about this war before, but now that it has affected my life to a great extent I am different,” she continued Oct. 22, 1942. “How long do you really (tell me the truth) expect this war to last?”

Bob didn’t know. But as he prepared to depart for the Army, he penned two replies.

One he gave to Elaine: “I hope we can get Dad’s car, darling, go to a football game somewhere, then maybe eat our supper out, go to the movies and last but not least go a million miles from nowhere just to be alone and talk about what we think and hope our future will be … Your soldier boy, Bob.”

The other he sealed in an envelope: “To Elaine Barbara Spencer, in case that I, Robert Van Ness Ransom, never return …”

Elaine soon watched Bob board a train for basic training. The oldest girl in a family of 10 children, she felt so alone.

“I said a prayer for you this afternoon after I got home,” she wrote to Bob. “This is what I said and what I am going to say every night before I fall asleep: ‘Dear God, please watch over my Bob and make him at ease and comfortable wherever he may be, and please, dear God, end this war as soon as it is possible and let my darling come back to me safe and well.”

Bob was saying his own prayer. The Army did not tell traveling troops where they were headed, how long it would take or what they would do when they got there. Instead, he was simply given two metal tags to wear around his neck.

“In case anyone gets killed in action is what the dog tags are for,” Bob wrote Elaine. “The government keeps one and they send one home.”

‘Last night I slept outside in a hole in the ground’

Bob learned how to be a soldier over the next year.

“Last night I slept outside in a hole in the ground,” he wrote to Elaine. “I couldn’t sleep though because it was so cold. At 3 a.m. in the morning they got us out of our foxholes and walked us 5 miles back to camp.”

Elaine, for her part, graduated from high school to a job at a military defense plant in Springfield. Her schedule: Wake by 5 a.m. Ride in the dark for an hour to work. Toil for 12 hours. Ride in the dark for an hour back home.

“I don’t hit the bed until about 9:15 p.m. because I have to take a bath every night,” she wrote. “You ought to see me in my coveralls and my hat … You see I can’t even write good anymore. My hands are all cut up from the chips that fly.”

Bob anticipated the Army was about to send him across an ocean to invade European soil taken by Germany or Asian territory seized by Japan. Training at Alabama’s Fort Rucker, he sent Elaine a telegram for Valentine’s Day 1944.

“Can you come to see me? Reply by wire. Take train to Dothan, Alabama. Take bus to Rucker. Let me know what you will need. Will write further instructions. Love, Bob.”

The message on Western Union letterhead filled only three lines. But Elaine could read the unwritten truth between them.

The bad news: Her first and only love was about to be sent far, far away to fight.

And the good: He wanted to marry her before he left.

Elaine stepped off the train and into Bob’s arms Feb. 19, 1944, but the wedding did not take place as planned. When Bob and Elaine went to see the Army chaplain, they discovered he was away on furlough. They had to wait more than a week for his return, then another day when they realized getting married on the leap day of Feb. 29 would mean an actual anniversary only once every four years.

Elaine had dreamed of a summer wedding amid fragrant flowers. Instead, the 19-year-old buttoned up a winter coat to start her big day March 1, 1944, walking from an Army mess hall to the camp chapel.

Elaine had packed a brown dress. Bob wore his dress uniform. A military buddy stood as best man. His wife, a stranger to Elaine, stepped in as matron of honor.

The newlyweds only had a few days to share a honeymoon before it all ended on Good Friday. Bob would wake up Easter Sunday and be off to an unknown battlefield.

“They just informed me I could tell you I was on my way overseas,” he wrote to his bride. “What ship I am on and where we are going, however, I can’t tell you.”

Bob did not know himself. But as Elaine saw by his postmarks, she knew her husband was speeding toward, and eventually sailing on, the Pacific.

“The ship sure is rocking tonight, dear,” Bob wrote in one letter. “Boy, was I seasick yesterday. I couldn’t eat a darn thing all day. I even threw up a Life Saver one of the boys gave me.”

‘I wish I knew just how dangerous it is’

Back on the home front, Vermonters faced their own turbulence.

When Elaine woke each morning for breakfast, she determined the day’s menu based on a book of ration stamps that limited everything from the food Americans put in their mouths to the shoes they put on their feet.

Bacon? Only if it fit into the government’s meat ration of 28 ounces a week.

Coffee? Only a pound every five weeks — less than a cup a day.

Sugar? Only 8 to 12 ounces a week.

Butter? Only 12 pounds a year — 25% less than usual.

Elaine fared no better at lunch or dinner but knew not to take her frustrations out on the stovetop or refrigerator door. You could not buy any new appliances, as materials and manufacturing were going for weapons and the tanks, planes and ships that transported them.

After breakfast, Elaine — who quit her Springfield commute as the nation stopped making cars and rationed gas and tires — walked to her 48-hour minimum workweek Rutland factory job. She rarely strolled in silk or nylon stockings, as soldiers flew off with the material for their parachutes.

Households saved everything from scrap metal to scrap paper to scrap rubber. Roll enough old tinfoil gum or cigarette wrappers into a ball, and you would reap 50 cents. Boil down cooking fat into glycerin, and you built up the country’s ammunition.

Elaine grew vegetables in a victory garden. Seeded what little she could save in War Bonds. Turned off the lights for air-raid drills. Turned on the radio and listened to the news.

“Honey, God knows you are in danger,” she wrote Bob, “but I wish I knew just how dangerous it is where you are.”

Then again, Elaine knew only too well. Her 19-year-old neighbor and high school classmate died in battle in 1944.

“Cpl. Clifford D. Grover of this city, father of an infant son whom he never had seen, was killed in action in France on September 20 while serving with an infantry combat division,” the local newspaper reported.

Clifford was the one who had seen Elaine write Bob letter after letter in study hall. The one who offered to escort her to senior class night so she would not be alone. The one whose wife and 8-month-old son remained next door.

“Tonight I could see her from our front-room window as she lay there on her bed with the baby in her arms,” Elaine wrote to Bob the day she learned of Clifford’s death. “Honest, I feel so sorry I had to move away before I started to cry again.”

‘I expect to meet you again someday’

Elaine would have to wait another year to hear church bells signal Germany surrendering across the Atlantic in the spring of 1945 and Japan doing the same in the Pacific that summer.

“There were thousands of people and cars, blowing horns, throwing paper, confetti and everything else imaginable,” she wrote her husband of that latter August day in Rutland.

Americans wanted to toss all the shortages, suffering, dread and destruction away. But the revelry was tempered by reality.

World War II would go down as the deadliest and most destructive conflict in history. The global toll has been estimated as high as 50 million men, women and children killed by shooting, stabbing, starvation, sickness, gassing, drowning, burning or bombing — 10 times the current Covid-19 death count of about 5 million people worldwide.

The war claimed the lives of 1,265 Vermonters, more than double the state’s 2020 and 2021 pandemic casualty total of 471.

As Elaine celebrated the end of fighting, Bob joined occupational forces in Japan. The world’s first atomic bomb annihilated Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, and the second incinerated Nagasaki three days later. The two explosions killed an estimated 214,000 people. But Allied leaders said they feared that, without such action, countless more soldiers would lose their lives.

“The day you get this letter I want you to thank God for how fortunate I have been while the war lasted,” Bob wrote Elaine. “I can tell you now that we were reserve for the Philippine Island invasions and also for Okinawa. This would have been it if the war hadn’t ended.”

The then 24-year-old soldier and his 21-year-old wife had yet to celebrate Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year’s or their wedding anniversary together. The two, in fact, had spent only a month of their marriage in the same place when his train rolled into Rutland at 2:30 in the morning Feb. 4, 1946.

Elaine saw the darkness pierced by the porch bulb, then a pair of cab headlights that careened around the corner. Wrapped in a bathrobe, she opened the door. The winter chill was numbing, but she never felt warmer or more alive as she melted into her husband’s arms, she would tell anyone who would listen.

Bob went on to work the assembly line of Rutland’s Howe Richardson Scale Co. until retiring in 1980. Elaine, for her part, gave birth to two daughters, who grew up, got married and gave her three grandsons.

Bob would face another battle — cancer — that took his life in 1999. Heartbroken, Elaine retrieved a box seemingly forgotten in the garage and began to reopen the 4,000 envelopes tucked inside.

That’s when I met Elaine. Walking into the newsroom where I worked in 2001, she showed me one of the letters.

Did I want to see the rest?

And so every Wednesday at lunchtime for a decade until Elaine died in 2012, I sat at her dining room table and listened to her read true tales of love, war and longing for the suffering to end.

Amid current-day complaints about too many Zoom calls, I still remember.

“My dearest wife,” Bob began one letter. “When you say no matter how long I am away you will always be the same when I get back, it makes me feel wonderful because I know you mean it so sincerely. The same goes for me, darling. Now, after the war and into the future, if you are around when I am going away for good, I will look into your eyes and say, I love you, darling, but I have got to leave you for a little while. I expect to meet you again someday in another world, and we will go on then as always before …”

And, through their archived correspondence, ever after.