BARRE — On the Monday before Thanksgiving, Amanda Boardman stood outside a two-story motel on busy Route 14 and watched the buses head north from the nearby elementary and middle school. School had just let out, and the buses proceeded in line, all labeled BUUSD: Barre Unified Union School District.

Her son was on one of them. Her daughter, though, was back in the family’s room. She was in quarantine.

Boardman’s two children — a daughter in fourth grade and a son in second grade — attend Barre City Elementary & Middle School. That is, when they attend school. During the fall Covid-19 surge, both kids have both been sent home for multiple stretches.

Boardman hoped this would be a normal school year, she said as she waited for her son to arrive. She and her kids were tired of masks, social distancing and, most of all, remote learning.

“But nope,” she said.

Since Vermont schools reopened in August, parents of young children have reported feeling a collective dread. At a moment’s notice, an email or phone call could announce their child must be kept home from school due to a potential Covid-19 exposure, forcing parents to scramble to cover work and child care for up to two weeks at a time.

In interviews throughout the fall semester, parents in one of the state’s hardest-hit school districts said the uncertainty and disruptions have been a constant. When classrooms close, parents have no choice but to bring their children along to work, errands or medical appointments, all during hours when kids would normally be sitting in a classroom, learning.

“It’s a lot of stress,” said Christine Baker, a single mother with two children in Barre schools. “And I have to unfortunately take it day by day because I never know.”

The lower grades in Barre have reported more total cases than in any other community in the state this fall, according to the Vermont Department of Health.

Two combined middle and elementary schools serve the area — one in Barre Town and one in Barre City. As of Nov. 30, they occupied the No. 2 and No. 3 slots, respectively, on the state’s tally of Covid-19 cases in schools. Barre Town reported 50 cases, and Barre City reported 45.

For schools, Vermont tracks cases only when a person is considered to be infectious — meaning those numbers under represent the true amount of virus circulating. State health officials also note that most school cases reflect broader community transmission, and the surge in Barre’s elementary and middle schools this fall coincided with peaks of infection in the surrounding city and town.

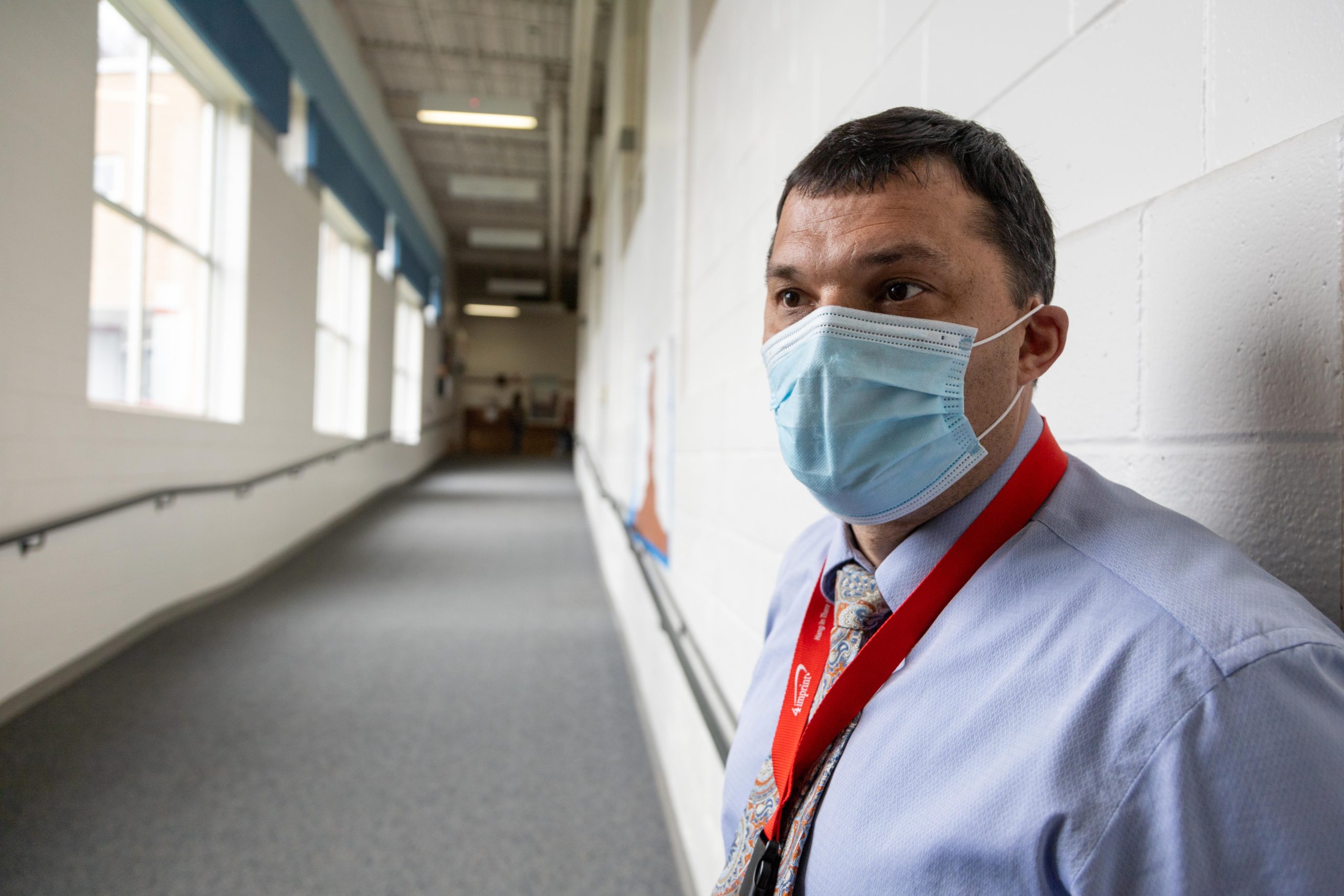

Pierre Laflamme, principal of the middle school grades at Barre City Elementary & Middle School, keeps a link on his computer’s desktop to a running tally of “line lists” — groups of students that have been notified, en masse, that they cannot come to school the next day because of a Covid-19 case.

As he scrolled past dozens of entries during an interview last month, Laflamme said the document barely conveyed the scope of the disruptions.

“There are multiple times when we’ve prepared a list, and we see a child’s only been back for three days from the last list,” he said. “We have students that, out of 50 days of school, have been out on a contact trace list (for) 20, 30 days.”

In communities like Barre, where longstanding inequities persist, school officials worry that Covid-19-related absences are widening the learning gap.

For many students, “when they’re not in school, they’re not in a good spot,” said Hayden Coon, Barre City’s elementary school principal. “And when I say not a good spot, I mean staying with many relatives in a hotel room or shared housing or a car. It’s not ideal in those conditions, and that ever-growing gap seems to have just heightened like crazy following the pandemic.”

Parents stretched thin

Boardman’s son’s bus stop is the Quality Inn, a motel where several rooms are occupied by participants in the state’s housing assistance program.

Boardman and her kids had stayed at the motel earlier this school year as part of the state program, she said. Hoping for more stability, she moved the family to Northfield to stay with a cousin, but the situation was “way out of control.” The cousin’s four kids were a bad influence on Boardman’s 7-year-old son, she said, and he started getting violent at school.

The family moved back into the housing assistance program, to a different motel up the road, in mid-November.

Boardman has some physical injuries and depression, she said, which keep her from landing a steady job. She spends her days looking for stable housing for the family, a challenge given the state’s lack of affordable units.

When her kids are home from school, they’re stuck in a motel room with her. That’s not conducive to Boardman’s apartment hunting, she said — or to her children’s education.

“It’s not easy for us parents,” she said. “We’re not made to be teachers.”

Christine Baker’s two daughters attend Barre schools. Her youngest is a fifth grader at Barre City, and her oldest is a sophomore at Spaulding High.

One morning in late October, Baker received a confusing message from the elementary school’s library: Her daughter had an overdue book, and she should return it when she was out of quarantine.

Baker had not been notified that her daughter was a close contact of a Covid-19 case. Was her child exposed or not? While the school sorted out the confusion, she had to keep her daughter home.

Baker works full time at Barre’s Salvation Army store. The calls or emails announcing that her daughter has to stay home come with little or no warning, she said, and her only option is to bring her daughter to work.

“I don't have day care. I don’t have a babysitter. I don’t have anybody. It’s just me,” she said. Even if she had backup, “Who wants to watch a kid who’s sick?”

Baker considers herself lucky that her daughters have only been sent home for cold symptoms and not for actual Covid-19 infections.

“God forbid they ever do come down with it, and then I lose time at work, which I really can’t afford to do,” she said.

She’s lost pay for leaving work early with her daughter, and her boss has grown frustrated with the repeated disruptions, she said.

Worse, Baker’s daughter falls behind in school. When she comes to the store, she sits alone in an office if she’s quarantining, or sits masked in the retail space if not. She has no laptop to use for class work.

Baker said she does not know what a better system would look like, but something has to change.

“I think it's coming down to, they don’t know what to do when they get a case, and they have to, unfortunately, have some kids not come to school,” she said. “I don’t think they have a backup plan. And if that happens, then they should have a much better plan.”

Many school leaders and public health experts warned in August that the state Agency of Education had failed to prepare districts for a potential surge in Covid-19 cases after the school year began. The highly contagious Delta variant had been driving up case counts for more than a month, but state officials forecast that a surge would be limited in duration and tempered by Vermont’s high vaccination rates.

The state pressed districts to open on schedule for full-time, in-person instruction with only two pages of nonbinding guidance on Covid-19 mitigation. That document provided off-ramps for mask-wearing, gave minimal specifications for testing and contact tracing, and declined to address ventilation or social distancing.

Crucially, after a school year when most districts had adjusted to hybrid in-person and remote learning models, the agency also shifted away from supporting virtual options. Parents say that although remote learning is flawed, it’s better than what many kids have received when they have been sent home this year: nothing.

Melissa Tobin-Davis, who also has two kids in Barre schools, worries that the lack of virtual options could set her Barre City seventh grader back.

Just days after she received the first of many email notices about a case in her son’s school, Tobin-Davis said, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. When she spoke to VTDigger, she was preparing for a surgical procedure that required a multiday quarantine for everyone in the household — including her son.

The school, however, had not set up protocols for remote learning. Tobin-Davis said she was told that staffing shortages and a lack of state support had scuttled the school’s planning.

“I understand that,” she said. “But my son needs an education. This isn’t his fault.”

Because Vermont is no longer in a state of emergency, schools are under pressure to keep their doors open, said Chris Hennessey, interim superintendent for the Barre school district. If schools send home more than half the student body on a given day, it won’t count as a school day, and they will have to make it up at the end of the year.

[Looking for data on breakthrough cases? See our reporting on the latest available statistics.]

Compared with last year’s hybrid structure, pivoting to remote learning on short notice presents major logistical challenges for teachers and students, Hennessey said. That’s most true in the youngest grades, where students barely had time to start using their devices this fall before cases started ramping up.

“It’s not like you just hand a young child a Chromebook and say, ‘have at it.’ There’s a lot of learning that goes with that, too,” he said.

Teachers have worked to provide more take-home materials for students to work on, Hennessey said. But that still presents equity issues around a student’s environment and level of supervision.

“In our view, even with these high case counts, we still think school is the safest place for our kids to be,” he said.

Tobin-Davis blamed relaxed rhetoric about the pandemic’s severity, including repeated comparisons to the flu, for some parents in the community now letting their guard down.

”It’s almost like things have gone back to the way it used to be,” she said. “You know, ‘Kids have a stuffy nose? OK, send them to school. No big deal.’”

Boardman, too, said she’s seen repeated disruptions caused by parents that refuse to comply with health guidelines. Many are still sending kids to school when they’re sick, she said, and that’s leading to more illness than the school can contain.

“The school is trying their hardest. They do what they can,” Boardman said. “There’s only so much they can do with all this going on.”

Short-staffed in a surge

Elementary and middle school administrators said they are troubled by the impacts of classroom closures — but they also are hindered by their own wave of staff absences. Many school employees are also parents in the community who have to stay home when their own children’s classrooms are closed.

On one day in early November, 43 employees out of about 170 at Barre City Elementary & Middle School were out, according to Hayden Coon, principal for the school’s elementary grades. That’s on top of about a dozen positions that remained unfilled as schools, like other sectors, face persistent hiring challenges.

It’s a frustrating cycle: Being short-staffed due to a Covid-19 surge has hindered the school’s ability to stand up programs, such as the state’s test-to-stay initiative, that are designed to help dampen the effects of a Covid-19 surge.

In that program, asymptomatic students take rapid Covid-19 tests every day for a week after an exposure, and those with negative results can stay in the classroom. Given the current case numbers, Coon said, “some days we're looking at 120 to 200 students we’d be doing test-to-stay for. And we do not have the capacity right now.”

That’s compounded the sense that the pandemic has hit communities like Barre harder than other places, Coon said.

The school participates in a range of government assistance programs, like federal Title I funding and the state’s Community Eligibility Provision, both of which are available to schools where at least 40% of families are low-income or qualify for free school meals.

While Covid-19-related disruptions have affected every family in the community, he said, they are more acute for those that are already living on the margins.

“Those who have the right supports in place, they’re able to access what they need to access. But try to send a kindergartener home to do remote learning, and they don’t have somebody there to support them — that’s not setting them up for success,” Coon said. “And that’s been unfortunately the case for a very large portion of our community.”

Sending home even one “core” or classroom — about 20 students at a time — can have lingering impacts, said Laflamme, the middle school principal. He worries the repeated disruptions are causing kids to lose their appetite for school altogether.

“The work we do with students is convincing them there’s value in this. There is value to being here. There’s value to learning,” he said. “When at the same time our actions seem to be in the opposite direction, right? ‘Send the kid home for this health thing.’”

The impact is visible at both ends of the school’s age range, Laflamme said. First graders are not learning “the game of school,” the soft skills and habits that will set them up for success in future grades.

Today’s eighth graders, meanwhile, have lost their usual optimism about the classes and activities they will be able to choose in high school, he said. “They’re just stuck in, ‘When is this going to be over? When is this going to matter? I’d rather just be home and not have to deal with fill-in-the-blank.’”

‘One bite at a time’

Some measure of hope was on display among parents and administrators alike when Barre City hosted a youth vaccine clinic in mid-November.

Over two days, the school dedicated a dozen staffers to supporting the state-run event. About 315 children in the newly eligible 5-11 age group were scheduled to get their first doses.

Inside the school’s gymnasium, children and their parents filed into curtained-off carrels where health department staffers and Vermont Medical Reserve Corps volunteers administered shots. Each station was strewn with toys, stickers and decorative bandages. Kids under observation after receiving their shots sat in rows of spaced-out chairs while “Monsters, Inc.” was projected on the gymnasium wall.

Among them was David Price’s 5-year-old daughter, Ronnie.

Price is immunocompromised and cares for his parents, who both have health issues. To minimize risk, he’s been homeschooling Ronnie since the start of the pandemic, an experience he described as “horrible.”

“She really needs to have the interaction,” Price said. “She doesn’t do well online, just looking through a computer. It just doesn’t work for her. She can’t stay focused.”

He planned to return Ronnie, fully vaccinated, to in-person classes for the spring semester.

Kelby Gilman’s two sons, Ryder and Kayden, both got vaccinated that week — one at the Barre City clinic, and the other at a state-run site in Berlin.

Both attend Barre Town Middle & Elementary. Last year, Ryder was homeschooled, and Kayden attended school in person part time.

Each made his own decision to get vaccinated, Gilman said. Kayden wants to wrestle at school, and vaccination for student athletes is strongly encouraged. Ryder said, “I just wanted the world to go back to normal so I can live a normal life again.”

Their mother was optimistic about the boys’ vaccinated future. Kayden is on an Individualized Educational Plan, she said, and the help he gets from teachers at school cannot be replicated at home.

“We’re making the best of it,” she said. “And both my boys did a really great job in their choices, so we’re pretty proud.”

Many of the families coming to the clinic were not from Barre, Laflamme said. But the school was still eager to support any effort to cut down on transmission and keep more kids in class.

“We’re not doing this for our school,” he said. “We’re doing it for the overall impact that it might have.”

Laflamme worries that the school is losing its connection to the broader community. Its annual open house was canceled this year, and the stress of classroom closures had fueled adversarial conversations between parents and administrators.

He is heartened by the fact that his staff are most vocal about things like allowing students to socialize more at lunchtime or to have older students help kindergarteners with their reading skills.

“That’s what people are fixated on,” Laflamme said. “Not, ‘Hey, when are we going to get to linear algebra? When are we going to introduce probability and statistics?’ Yes, curricular learning is important, but people’s first line of questions is: How do we come back to being human-centered? How do we just be a community again?”

Hennessey, the superintendent, hopes more testing will help. Community members have volunteered to help implement a test-to-stay system starting in January, he said, and the district has brought on a volunteer coordinator to lead the effort.

Laflamme said he does not have all the answers about what should happen next. But the youth vaccination effort is a start.

He often returns to a familiar idiom: How do you eat an elephant?

“One bite at a time,” he said. “That one little piece that helps us move further down the line to getting some kind of protection, some kind of response, understanding, clinical knowledge about how to treat things — that will move us away from this constant state of uncertainty, fear and ambiguity we feel so trapped in.”

Get the latest statistics and live updates on our coronavirus page.

Sign up for our coronavirus email list.

Tell us your story or give feedback at coronavirus@vtdigger.org.

Support our nonprofit journalism with a donation.