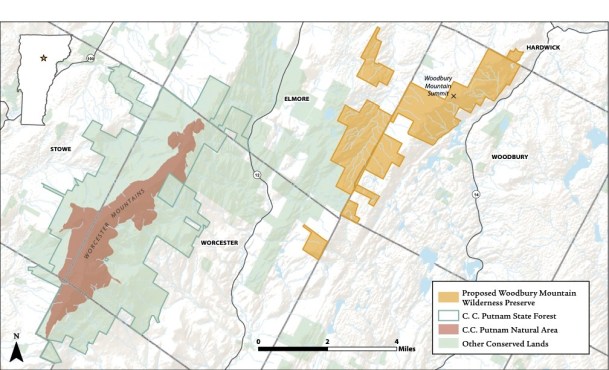

Several thousand acres of forest in Woodbury and Elmore, owned by a family with a long history in the timber industry, will soon be preserved as “forever wild.” Under the plan, the land would never be logged again.

The 5,400 acres, part of a critical wildlife bridge from Vermont to the White Mountains in New Hampshire to forests in Maine, contains wetlands, a mountain summit and 36 miles of headwater streams of both the Winooski and Lamoille Rivers.

It would join just 3% of forests in the state managed using an approach called passive rewilding, allowing the forest to reach old-growth status in the future.

“There’s few places in Vermont where you can get this kind of vast and remote feeling,” said Jon Leibowitz, executive director of the Montpelier-based Northeast Wilderness Trust, which plans to buy the property. “Having it be so close to our capital city is a pretty extraordinary opportunity.”

The Northeast Wilderness Trust will keep the land open to foot traffic and other nonmotorized recreation, along with hunting of abundant prey species, such as white-tailed deer. Legal rights-of-way will remain open for ATVs and dirt biking.

In the 1950s, Hugo Meyer bought a number of mostly contiguous parcels in Worcester, Elmore, Woodbury, Hardwick, Walden, Cabot and Marshfield. His son John Meyer, who studied forestry at the University of Vermont, helped manage what his father called his “tree farm” for timber, taking over in the 1970s. When his father died years ago, the next generation inherited the land.

“This second generation, there are five of us and we’re all in our 70s or even 80s,” John Meyer said. “And we’re looking ahead to the future — what is the legacy of having had this land and cherished it and taken care of it for 70 years? What do we do with it?”

They agreed it should be conserved, he said. Over the years, they’ve sold pieces to the Vermont Land Trust, so that it might resell to other forestry operations. When they went to sell the Woodbury Mountain complex, the Northeast Wilderness Trust stepped in to express interest.

Courtesy of the Northeast Wilderness Trust

The organization is the only land trust in all of the Northeast that is focused exclusively on “forever-wild” conservation, according to Leibowitz.

“At first, we weren’t quite sure what to make of that, because our history had been timber production, timber management,” Meyer said.

But when he went back to look at his records, he realized that, between the revenue from the timber and the family’s property taxes, they’d barely broken even. The mountainous terrain is hard to reach, and winter skid trails — frozen roads that allowed machinery to scale the mountain more easily — weren’t freezing all winter long anymore.

“As a forester, and as someone who really lobbied against this sort of thing in the Legislature years ago as a general policy issue, I had a change of heart when I looked at the data,” Meyer said. “For this property, it is the best possible solution going forward.”

The tract of land, Leibowitz said, is special because of its diverse habitat types, which can support a range of species. It will help wildlife move across the region, which will become increasingly important as the climate continues to change. The land has been identified by the Staying Connected Initiative as an important wildlife corridor for the state and region, Leibowitz said.

It acts as “a bridge or a stepping stone,” Leibowitz said, from the Green Mountains, to the Worcesters — the last undeveloped mountain range in Vermont — into the Northeast Kingdom.

“Of course, if we go even further beyond, it links directly into the Whites, and the western Maine mountains — some of the most intact temperate forests on the planet,” he said.

Wild forests come with a suite of ecological benefits. As forests mature, their capacity to filter water, prevent flooding, suck carbon from the atmosphere and support diverse life grows, said Zack Porter, director of Standing Trees, an organization that advocates for more protection and restoration of Vermont’s public lands.

Vermont Conservation Design, a plan endorsed by Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department, says that managing about 9% of Vermont’s forests for passive rewilding “will bring this missing component back to Vermont’s landscape and offer confidence that species that benefit from or depend on this condition can persist.”

“We hear a lot about the value of the old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest,” Porter said. “Our forests here are very similar in many respects. Our forests grow for a thousand years between major disturbance events. And what that means is that our forests can continue to sequester and store carbon over very long periods of time.”

The land, a bridge between wild regions, may also provide a bridge between environmentalists and foresters, two groups between which conflict often simmers. Meyer said it’s a balance — he’d support passive rewilding of select forests, and working forests should be protected, too.

“If it has more value to society as a working forest, because it’s got good sites, good access, and can produce good stuff, it needs to be managed,” he said. “Everything is a compromise and balance.”

Leibowitz said he values working forests, too. He hopes the relationship between the Meyer family and the Northeast Wilderness Trust could serve as a model for others.

“I hope it brings hope to communities when they’re grappling with what I believe is a false narrative,” he said. “Between wild lands or woodlands — it’s not ‘or.’ We need wild lands, and we need woodlands. And at only 3% of all of Vermont that is conserved as wild, there’s clearly a lot more room for wild lands on our landscape.”

Clarification: The preservation plan means the land would never be logged again. An earlier version of this story misstated that point.