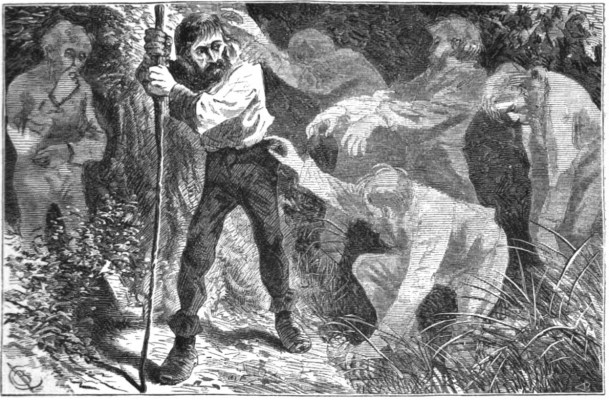

At first glance, the dark figure on the trail looked like a small bear. But the form soon resolved itself into that of a man, an almost unimaginably skinny man.

His filthy clothes didn’t seem so much tattered as shredded. His face was dark and leathery, apparently from long exposure to the elements. This, the two searchers realized, must be their quarry.

“Are you Mr. Everts?” one asked. “Yes. All that is left of him,” came the reply. With that, the hunt for Truman Everts ended.

Everts, a Vermonter who had been part of an expedition into the Yellowstone region of Montana, had been missing for five weeks and was presumed dead. A judge had offered a $600 reward for whoever found Everts’ body, which is what set these mountain men, “Yellowstone Jack” Baronett and George Prichette, on Everts’ trail.

That Everts survived seemed miraculous, all the more so when he described his experiences during the 37 days since he was last seen.

Most of what we know about Everts comes from an article he wrote in Scribner’s Monthly in 1871, the year after his near-death experience in Yellowstone. Other than the Scribner’s piece, even the basic outlines of Everts’ life were unknown until 1961, when his son, also named Truman Everts, walked into a visitors center at Yellowstone.

That day, National Park Service staff learned that Everts had been born in Burlington in 1818. One of six sons of a sea captain, Everts had worked as a cabin boy during several of his father’s voyages on the Great Lakes. Little else is known of his life before 1864, when he won appointment as assessor of internal revenue for Montana. He was fired from that job in 1870, however.

Everts was between jobs when, at age 52, he joined the Washburn Expedition to Yellowstone in August 1870. The expedition would ultimately help the effort to make Yellowstone America’s first national park two years later.

You can read the events that followed in one of two ways: Either Everts was extremely unlucky during the expedition and should be celebrated for surviving so long in the wilderness, or he was so clumsy and ill-suited to such an endeavor that he should never have been allowed to join.

Things got sticky for Everts three weeks into the trek when he got separated from the group. He thought little of it at first; he’d gotten separated before and had always soon rejoined the others, he explained in Scribner’s.

When he lost sight of the group this time, he had a plan. He stopped at a clearing, leaving his horse unhitched, and went to look for a route to Yellowstone Lake, where he expected to find the others.

Things quickly got worse, far worse. The horse ran off with his blankets, matches, rifle, pistols and fishing tackle. Everts spent the rest of the day searching in vain for his horse. Only then did he appreciate that his situation was one of “actual peril.”

Fear started to overtake Everts, who admitted to being “(n)aturally timid in the night” (i.e., afraid of the dark).

Everts had gone three days without eating when he noticed a patch of elk thistle, which a botanist had told him was edible. “Eureka! I had found food!” Over the next five weeks, he would subsist largely on this plant, which is sometimes referred to today as Everts thistle.

After eating, he lay down drowsily beneath a tree. His sleep was pierced by a humanlike scream, which he quickly recognized as a mountain lion’s. Everts bolted up a tall tree and responded to each of the big cat’s screeches with a scream of his own. Below in the darkness, the lion, undeterred, continued to circle. Everts took a different tack. He tried silence. The cat gradually lost interest and wandered away. Exhausted, Everts climbed down and went back to sleep.

In the morning, Everts noticed a change in the atmosphere. A storm was coming. Snow soon fell heavily. Everts spread spruce branches for a bed, then covered himself with dirt and tree boughs. There, for two days, he lay waiting out the storm. At one point a small bird, “denumbed” by the cold, hopped within reach. Everts seized the bird, killing and plucking it before eating it raw. “It was a delicious meal for a half-starved man,” he wrote.

He decided to walk on and eventually found a group of the geothermal features, including steam vents, hot springs and mud pots, for which Yellowstone is now known. Craving warmth — his feet were frostbitten — he lay between two of the holes for warmth. “I was enveloped in a perpetual steam-bath. At first this was barely preferable to the storm, but I soon became accustomed to it, and before I left, though thoroughly parboiled, actually enjoyed it.”

As he lay there, the sun emerged and lit a nearby lake. Only then did he think of the opera glasses (small binoculars) he was still carrying. He used them to start a fire. “(I)f the whole world were offered me for it,” he thought at the time, “I would cast it all aside before parting with that little spark.” That moment of hope proved short-lived. While he was sleeping beside the steaming holes, the ground beneath him gave way and Everts’ hip was badly scalded.

Everts proved altogether unsafe around fires. Once he somehow managed to lurch into his campfire, burning his hand; and twice he awoke to find his campfire had turned into a forest fire. “The grandeur of the burning forest surpasses description,” he wrote. “… I never saw anything so terribly beautiful.”

Everts seemed to be losing his mind. He hallucinated that an old friend visited to offer advice. When the friend’s visits ended, Everts imagined a new set of friends — his stomach, arms and legs. He had to cajole each to do its job.

He dreamed of elaborate feasts. “I would apparently visit the most gorgeously decorated restaurants of New York and Washington; sit down to immense tables spread with the most appetizing viands (meats); partake of the richest oyster stews and plumpest pies.”

In reality, Everts was wasting away. He was said to weigh only 50 pounds when he was found.

Baronett and Prichette took Everts to an empty miner’s cabin 20 miles away. Then one hiked 70 miles to get help while the other stayed with Everts. The poor man was frail and seemingly near death when an old hunter happened on the cabin. Seeing Everts’ condition, the hunter said he could cure him. He melted bear fat and had Everts drink a pint of the liquid.

The prescription seems to have worked. Everts put on weight and made his way out of the wilderness.

In 1872, Everts resisted suggestions that he become Yellowstone’s first superintendent. Not because he was unqualified, but because the position had no salary. He migrated east. In the 1880 census, he was a farmer in Kentucky. Ten years later, he was a postal clerk in Washington, D.C. The following year, he married Imogen Schooler. Some people gossiped that she was only 14 at the time — she was actually 23. Still, Everts was 49 years her senior.

He died in 1901. The judge who had offered a reward for finding Everts never paid Baronett and Prichette. Technically, he had offered the money for recovering Everts’ body, not the living man.

Some years later, Baronett visited Everts, who treated him brusquely. Everts rejected Baronett’s suggestion that he pay the reward himself. Everts insisted he was on the verge of rescuing himself when Baronett and Prichette came along.

Baronett later remarked that they should have “let the son-of-a-gun roam.”