Wetland restorations planned near Willoughby Lake will be the largest such project in the state since 2011. The project falls under a federal and state program created that year in which developers pay fees when they impact a wetland so a comparable piece of land can be restored.

“It’s a pretty exciting site,” said Laura Lapierre, wetlands program manager for the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation.

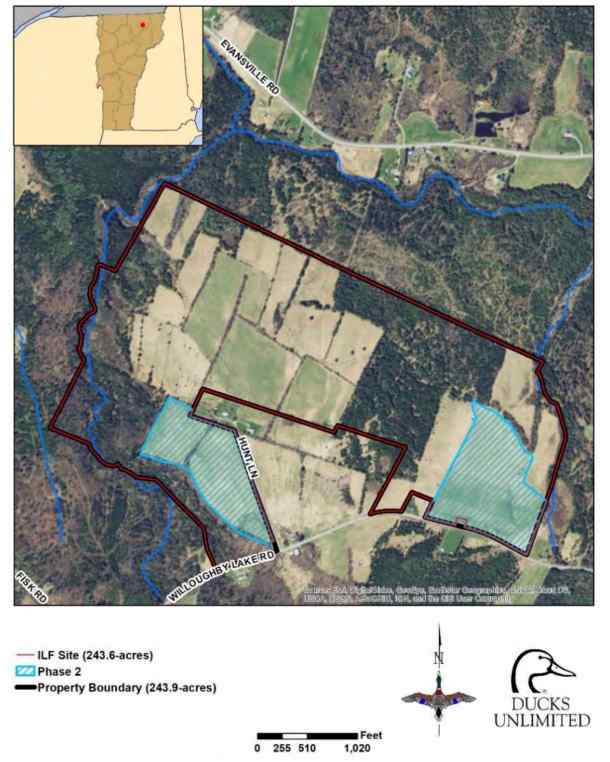

The 244-acre parcel sits north of Willoughby Lake Road in Barton, at the intersection with Hunt Lane near the town forest. The former farm was bought in 2019 by Ducks Unlimited, a national conservation nonprofit organization that rebuilds and protects wetlands for the program in Vermont.

The wetlands abuts Lord Brook, a tributary of the Willoughby River, which connects Willoughby Lake with Lake Memphremagog to the north and is renowned for plentiful steelhead rainbow trout.

“What really stood out about the Willoughby property was its proximity to large bodies of water that attract waterfowl,” said Patrick Raney, conservation services manager for Ducks Unlimited.

Wood ducks, black ducks and mallards all use the bodies of water around the wetlands, Raney said.

The property also appealed to Ducks Unlimited because it covers a diverse range of habitat types, he said. The tributaries it borders are home to invertebrates and small fish, and there are extensive tracts of forested wetlands there, he said.

Ducks Unlimited, in a March 2020 report to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, said the site has “unique potential to reestablish a forested wetland community.”

One of those forested wetland types in particular — northern white cedar swamps — frequently features rare plant species and high plant diversity. The swamps are habitat for 20 to 30 species per square meter, Raney said, among the highest rates of plant diversity in the Northeast.

“We should have a really nice mosaic of different cover types, which should really maximize wildlife usage and diversity on the site,” he said.

Raney said the land cost more than $300,000. The money came from the developer-fee program, which is overseen by a review team made up of federal and state agencies.

When seeking permits for a construction project, a developer buys credits if their work will impact a wetland. The funds from those credits allows Ducks Unlimited to roll out restoration efforts. The fees are based on property values in the region where a project is considered. Willoughby Lake is part of the program’s St. Francois service area, where one credit costs a little more than $180,120.

Lapierre, the Vermont wetlands program manager, said the idea behind the program is to ensure that, when a developer with a permit is going to affect a wetland, a comparable piece of wetland will be protected.

“Wetlands have significant functions and values in the landscape,” she said. “They’re these concentrated areas that have a large amount of biodiversity, lots of different plants and animals.”

They can filter water, store flood waters and prevent erosion, too, she said.

Most of the money for the Barton site came from fees paid several years ago by the state Agency of Transportation for construction at the airport in Coventry, which is also in Orleans County, Lapierre said. The agency received a permit in 2014 to expand the airport, including a 1,002-foot runway extension. Most of that project’s wetland impact came from the removal of forested wetland as a safety precaution. Lapierre said the agency’s payment in the program was nearly $842,000.

Work on the ground hasn’t begun yet, Raney said. His organization now owns the site but needs another $300,000 to $400,000 to complete construction. While Ducks Unlimited is raising money, the nonprofit is also navigating federal and state paperwork, he said, so field work isn’t likely to begin in earnest for a couple of years.

The organization went ahead and bought the land because developments that pay into the wetland program aren’t all that common in the Northeast Kingdom, he said.

“We kind of went for bust on acquiring a large property,” he said.

The restoration will be broken into two phases. Part of the plan is to “put back a lot of the roughness” in the land, Raney said. Because the property was used for agriculture for “probably well over 100 years,” much of the parcel has flattened, with fewer nooks and crannies for water to pool in, he said. Ducks Unlimited will try to re-create the wetlands with new shallow areas where water can collect in the way it would have naturally before the land was transformed by agriculture.

Ultimately, the nonprofit plans to retain a conservation easement and turn the property over to a local land trust, Raney said.