Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

As midnight approached on March 21, 1844, a farmer in Rutland climbed on his barn roof, then, sporting a pair of homemade wings, awaited the hour of reckoning. When it came, the farmer took a literal leap of faith off the barn and, he prayed, into the loving arms of his Lord.

The strangest thing about the farmer — whose name has been lost to history, but whose deed was recalled by his neighbor — is that his behavior did not stand out from the strange way countless others were acting in 1843 and 1844.

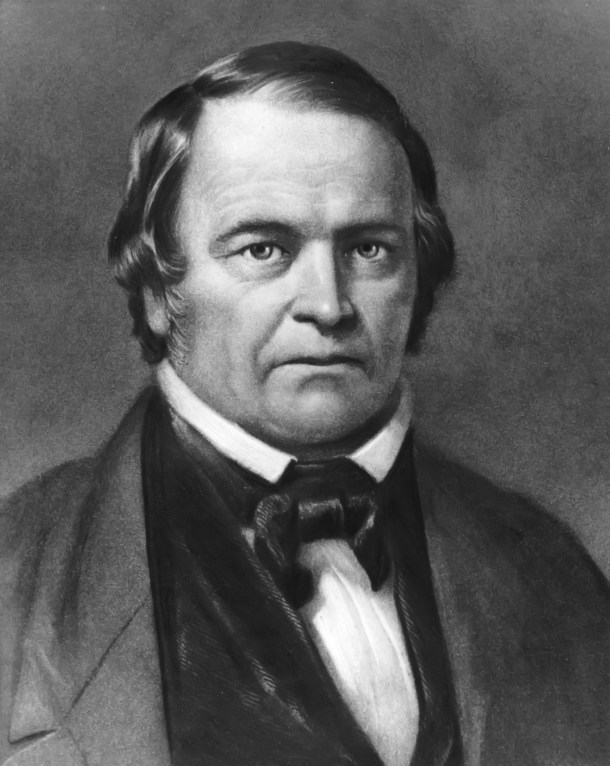

The country was in the thrall of William Miller and his prediction that the Second Coming of Christ was imminent. Miller’s following was so strong that even those who mocked him can be excused if they glanced nervously skyward on the appointed day.

Miller’s prediction created a national phenomenon, but it had roots closer to home. Growing up and educated in the Poultney area, Miller was reportedly an atheist who mocked religious rituals as mere superstition. Others said he was deist, and thereby believed that God created the world but doesn’t intervene in how it functions.

Atheist or deist, clearly, something changed his worldview. Historians’ best guess is that it was the War of 1812. Having enlisted in the U.S. Army, Miller was a captain when the Battle of Plattsburgh occurred in 1814. He wrote to his wife of the overwhelming scene he witnessed:

“How grand, how noble, and yet how awful! The roaring of cannon, the bursting of bombs, the whizzing of balls, the popping of small arms, the cracking of timbers, the shrieks of the dying; the groans of the wounded … the swearing of soldiers – the smoke, the fire, everything conspires to make the scene of … battle awful and grand.”

Perhaps this was the moment Miller, then 20 years old, first seriously contemplated death and the hereafter. More skeptical observers have linked his later religious beliefs to a wound he suffered during the war. While Miller was being transported to the hospital for treatment of a leg injury, the wagon carrying him lurched and tossed him out headfirst. This injury proved worse than the first, leaving him unconscious for several days.

Whatever the cause, Miller began reading the Bible methodically, searching for revelations. After years of contemplation, he came up with a stunner. According to his reading, Judgment Day was fast approaching, and he believed he knew when. By following clues he said were in the Bible, Miller announced it would occur sometime “around 1843.”

Ordinarily the prophecies of a solitary, self-styled biblical scholar would have gone nowhere. But social conditions in the United States were ripe for that kind of message and messenger. The nation was still feeling the effects of the Second Great Awakening, the religious movement that swept through the Northeast beginning in the 1820s. Preachers conducted their revival meetings with an extreme sense of urgency, believing that the Millennium, Christ’s prophesized return to Earth, was at hand.

Furthermore, the new religious fervor was tinged with the democratic spirit of the young nation. Anyone could offer religious insight. Miller, who had been without a pulpit, got the call to preach in 1831 in place of an ill pastor. Believing this opportunity was divinely inspired, he made the most of it.

Miller told the congregation of his prediction, but said that several things would occur first: The Earth would tremble, wars would erupt, mankind’s genius would make significant progress, and people would see marvels in the sky.

Quickly his prophecies seemed to be coming true: As they predictably do, earthquakes and wars continued to happen. Furthermore, the United States was in the midst of creating unprecedented technological wonders like the Erie Canal.

When, on the night of Nov. 13, 1833, people saw a massive meteor shower, Miller was looking pretty smart. Preachers, perhaps as many as a thousand of them, started to spread his prophecy and win converts. Over the next decade, an estimated 100,000 people joined Miller’s cause.

As the decisive year of 1843 approached, people greeted it with a mixture of dread and hope. Miller had never set a date for the Day of Judgment, but followers said it would come on March 21, the first day of spring.

In Vermont and elsewhere, followers stopped making plans beyond that date. They gave away their property and left their fields unplanted. Why not? The Lord was coming and they would never need food or possessions again.

On the appointed day, Millerites everywhere gathered. In Wardsboro, a group assembled in the graveyard, crying and yelling in their excitement. With them was the shrouded body of a woman who had recently died. Like others in the region, her family believed that burying the dead would only delay their rendezvous with God. A selectboard member went to the graveyard to complain about the macabre gathering.

After giving away their possessions, Millerites in Calais climbed upon the roof of their church. There, dressed in white “ascension robes,” they prayed and waited. When the sun rose the next morning on an unchanged world, they descended to the hoots of amused onlookers. It is hard to say which was worst: the derision, the disillusionment or the sudden poverty. Thousands of other followers throughout the Northeast suffered the same fate.

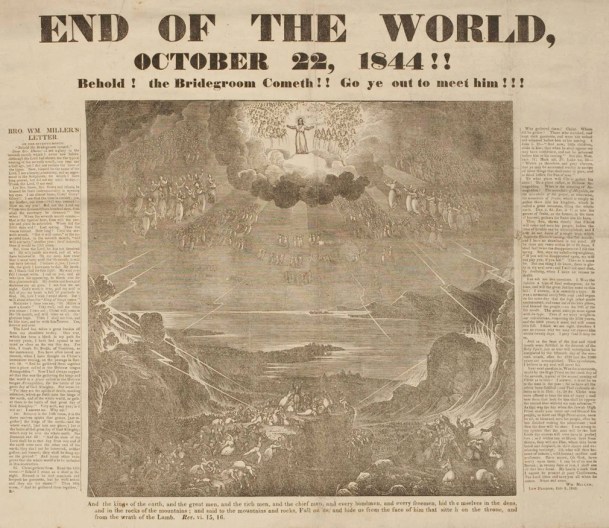

The anticipated “Great Reckoning” had become “the Great Disappointment.” Miller responded to criticism by saying that the date had been right but the year wrong. Judgment Day would come on March 21, 1844. Similar disappointment arose with dawn on the morning of March 22, 1844. At which point, Miller rechecked his figures and came up with what he said was the true day: Oct. 22, 1844. That date, of course, proved no more prophetic than the previous two.

Perhaps Miller understood that his predictions had a wide margin of error. As the supposed Judgment Days came and went, he is said to have built new stonewalls on his property and kept his larder well stocked.

Around Vermont and the rest of the Northeast, followers eventually lost faith in Miller.

As 19-year-old Harriet Hutchinson of East Braintree explained in a letter to her fiancé dated Dec. 1, 1844: “Miller’s project has failed, Millerism is pretty much down about here. I think it has done a great deal of injury–there were some that did not harvest their grain until very late if they have at all, they were so sure the world would come to an end this fall … and they should not want any more provision, therefore their families are made destitute.”

Hutchinson refused to mock the Millerites. “I had my fears about it (that Miller was right),” she confessed, “but never was a believer, very far from it.”

After Miller’s third failure, few of his followers remained. Most amazing about the Miller phenomenon is not that so many people believed him in the first place, but that so many stuck with him for so long. Perhaps followers found themselves too far out on that particular limb of faith to turn back. Among them was that farmer from Rutland whose figurative limb was a literal barn roof. His fall broke his leg, but not his spirit. He later became a deacon in his local church. The man had given up on Miller, but not on religion.