BROWNINGTON — The legacy of Alexander Twilight is kept close along the soft slopes of Orleans County.

It’s where the nation’s first African American college graduate built Athenian Hall, a dormitory for the boarding school he ran up the hill. The 1830s granite building in Brownington is now home to the Old Stone House Museum, whose staff and volunteers hope this year to discover more about the man as they celebrate his 225th birthday.

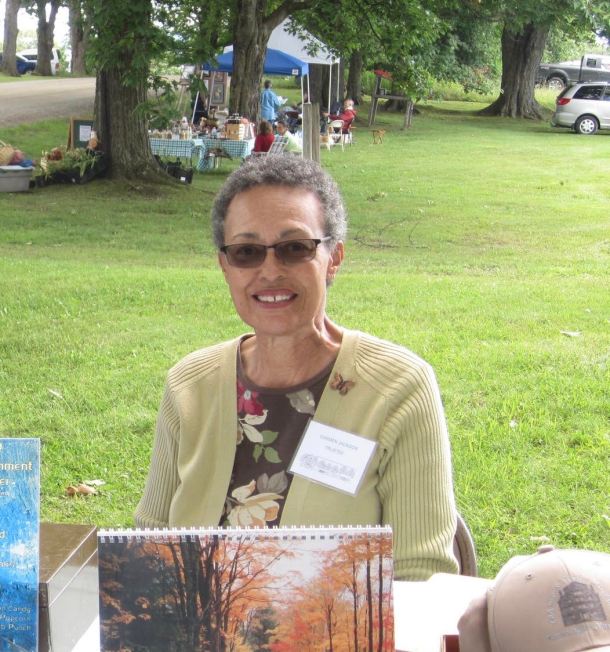

“Throughout the museum, we have little bits and pieces of his life,” said Carmen Jackson, board vice president for the Orleans County Historical Society, which runs the museum. “We want to put that all together so you can say, ‘Aha, that is Alexander Twilight.’”

Throughout the museum’s mid-May to mid-October tour season, staff and volunteers roll out a constant string of educational activities: student field days, historically themed paint-and-sips, time-traveling day camps, collectors’ fairs and more.

All those events feature the story of Twilight in some way or another, said Molly Veysey, the museum’s director. But in the run-up to the educator’s birthday Sept. 23, Veysey wants to bring him to the forefront for people.

“A fleshing out of a person who they’ve heard about their whole life,” is how the director put it.

Born in Bradford, Twilight pioneered educational techniques still used today — experiential and place-based teaching, Veysey said.

“He was doing all of it — and well — in 1830,” she said.

He ran the Orleans County Grammar School in Brownington and preached in a church in town. Throughout his career, he taught more than 3,000 students, a third of them girls.

Along with being the first black person to graduate from an American college — Middlebury, in 1823 — Twilight also became the first to win election to the Legislature. He served in 1836.

Those broad strokes make up most of what people know about Twilight.

“Really, there’s relatively very little known about him,” Jackson said. “We really don’t know that much about the man.”

That’s likely due, in part, to his racial heritage, Jackson and Veysey said. Slavery, racism and its byproducts often muddy genealogy for black Americans, with limited record-keeping and families that were broken up.

Despite living as a free black man during the 1800s, Twilight may not have faced waves of discrimination, the two historians believe.

Twilight, whose father was black and whose mother was believed to be white or biracial, had a light complexion, and some people may not have realized his black heritage.

“He was really remarkable,” Veysey said. “I don’t think he found much hindrance.”

Jackson, who is African American, thinks Twilight’s driven nature found acceptance in Vermont. She and Veysey recounted how he pushed to build the granite dormitory even though his school board opposed the idea.

“I really think that’s a very Vermont attitude — ‘gotta git ‘er done,’” said Jackson. “And I think Vermonters respect that.”

Expanding the public awareness of Twilight’s accomplishments could be significant to populations marginalized in the state.

“For those children to have some recognition of their heritage is significant — and especially here, in northern Vermont,” Jackson said.

As part of the birthday-year plans, the two said they’ve been talking to area lawmakers — Sens. John Rodgers and Bobby Starr and Rep. Vicki Strong — about introducing a proclamation in the Legislature in April. It would honor Twilight for his pioneering but little-known role in history.

They said they’ve spoken with staff for Rep. Peter Welch, D-Vt., too, about the congressman making an announcement at the federal level.

And the museum reps have been talking to state officials about revising the historical marker outside the Old Stone House. Right now, it doesn’t acknowledge Twilight’s race, and Veysey and Jackson would like to change that.

If all goes as planned, a new historical marker would be unveiled at the museum’s Sept. 20 celebration of Twilight’s life.

The museum has been working to transcribe sermons handwritten by Twilight to include in some of its events.

“Ideally, I would like to see somebody in the church preaching,” Jackson said.

Those preserved documents offer some of the only available insight into Twilight’s life. With so much still a mystery, Veysey wonders if she and other museum workers are one generation too late — descendants of Twilight’s students are long gone.

But Veysey and Jackson hope the year’s events could draw more records, more memories.

“Maybe this will bring people out,” said Jackson. “It just might uncover some things.”