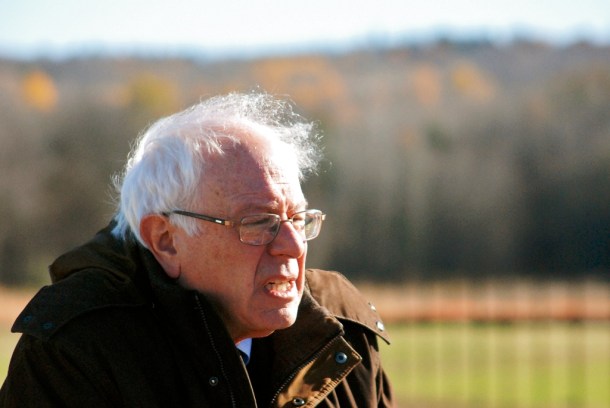

In the early 1990s, as a new congressman in Washington D.C., Bernie Sanders would escape to Vermont on weekends where he and his senior adviser, Anthony Pollina, drove around the state to meet with constituents.

During those hours in the car, the two shared ideas on environmental policy — seeds that form the basis of his recent $16 trillion plan to combat climate change.

Decades later, as Sanders carves out a position in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary field, he has announced an ambitious platform to combat climate change that includes reaching 100% renewable energy by 2030 and zero carbon emissions by 2050. Sanders contends the plan will create thousands of jobs.

The proposal would help low income families buy electric vehicles and upgrade the nation’s railway system with high speed tracks and trains.

The plan would also address remediation of chemicals that have been found harmful to human health. The Vermont senator included almost $35 billion to repair the country’s drinking water supply, targeting low income communities — like Flint, Michigan — to solve the issue of drinking water contaminated with toxins such as lead and PFAS — which have been linked to cancer and birth defects.

Sanders would dramatically reshape agriculture practices by plowing $410 billion into regenerative farming systems and rebuilding rural communities. Another $25 billion would be used to help farmers make conservation improvements.

The plan would also give people living in rural areas the right to protect land from chemical and biological pollution, including pesticides and herbicides. Rural residents would have “legal recourse to sue farmers who pollute their property.”

Sanders has not said how he would pay for the sweeping initiatives, which would radically change the way the nation does business.

More fundamentally, Sanders has not explained how he arrived at this sea change in his own thinking. Until recently, climate change has been a sidelight of the senator’s presidential platform.

Economy first, environment second

Sanders has earned an iconoclastic, loner reputation in Congress on economic issues including income inequality, campaign finance and the high costs of health care.

Environmental issues were not his forte.

“In terms of where he devoted his energy in the Senate and the House, before that, it was to issues of economics, financial power, things like that,” said Eric Davis, professor emeritus of political science at Middlebury College and longtime observer of Vermont politics.

Some who have known Sanders through the years credit Pollina, a state senator representing Washington County, for cultivating Sanders’ interest in environmental issues.

Pollina doesn’t disagree.

“Well, I don’t want to take credit for Bernie Sanders’ awareness of environmental issues necessarily — you would have to ask him — but I think there might be some truth to that,” Pollina said with a laugh, in a recent interview.

The Sanders campaign declined to comment on the senator’s environmental record.

Pollina’s partnership with Sanders dates back to the 1980s, before Pollina joined his congressional staff in 1991.

While Sanders was mayor of Burlington, Pollina founded Rural Vermont, a grassroots farm advocacy group.

Pollina tied the environment to the local economy in his unsuccessful bid in 1986 for a Vermont House seat. And in the run up to Sanders’ bid for Congress, Pollina introduced his friend and future boss to farmers throughout the state. In these meetings, Sanders had conversations about land use, environmental concerns for rural communities, and the importance of open spaces, Pollina recalled.

These early discussions and time on the road forged a bond between Pollina and Sanders, who worked together on property tax reform.

At the time, Pollina pushed to keep land in agriculture and lobbied to reduce the property tax burden on farmers. Meanwhile Sanders was working on property tax issues in Burlington, trying to keep the city affordable.

“We spent a lot of time on the weekends traveling the state visiting with folks and going to meetings and what not. So we had a lot of conversations and I think that the awareness that corporate decision-making was impacting the environment was one thing that he was very clear on,” said Pollina in a recent interview.

Growth tied to the environment

Peter Clavelle, who was the director of the Community and Economic Development Office in Sanders’ administration and later became mayor, said that as mayor, Sanders embraced a series of environmental principles to guide growth and development, Clavelle said.

“If you were smart about it, you could create jobs by cleaning up the environment,” Clavelle said.

During Sanders’ time in the Burlington mayor’s office, the city saw one of the largest environmental projects to date in the state of Vermont: a $53 million upgrade to the city’s sewage and stormwater system funded by the state and city. He was also at the helm in Burlington when the city landfill was closed and capped.

“Before the term sustainable development or sustainability became part of our regular vocabulary, Burlington was charting a path to becoming a more sustainable community,” Clavelle said.

Pollina also said that though Sanders may be better known for his economic stances, environmental objectives have also long been part of his work.

“He’s always had a special focus on economic justice and a lot of people would say maybe the environment was not his No. 1 issue, but I think he’s showed he was more than willing to stand up for the environment when it came time to do things,” Pollina said of Sanders.

After Sanders won the election, Pollina joined Sanders’ staff as a senior policy adviser, a title he would hold until 1996.

When he was hired, Pollina told the Burlington Free Press that he intended to focus on mobilizing grassroots movements.

“We intend to mobilize Vermonters rather than just reporting to them what’s happening in Washington,” Pollina said in 1991.

During his first two terms in Congress, Sanders and Pollina fought for more congressional oversight of manufacturing companies that were exposing employees to harmful chemicals.

Sanders and Pollina traveled to Georgia to meet with workers in the carpet manufacturing industry to learn how their health was being affected by chemical exposure.

Sanders went on to hold congressional hearings on toxins commonly found in carpets and paints used in work environments and homes. He worked with then-Rep. Joe Kennedy II, D-Mass., to get the Indoor Air Quality Act of 1993 passed — one of only two environmental bills to become law that year.

“The connection between corporate responsibility and environmental degradation was really clear to him and important to him. And the connection between economic justice and environmental justice,” Pollina said.

Climate change & renewable energy

Sanders’ main target in those first two terms was exposure to environmental toxins and genetic engineering.

In the late 1990s and the early 2000s, Sanders began to focus more on climate change and renewable energy.

While the Vermont independent was in the U.S. House, Bill McKibben, the environmentalist and co-founder of 350.org, said he would regularly accompany Sanders to town hall meetings in Vermont to talk about climate change and renewable energy solutions.

During President Barack Obama’s tenure in the White House, Sanders, then a senator, would fight against the controversial Keystone oil pipeline, which became a symbol of the battle over climate change and fossil fuels for many environmentalists.

“When we started the fight against the Keystone pipeline, he was the only senator willing to stand up to the Obama administration about any of this,” McKibben said.

David Blittersdorf, a renewable energy entrepreneur and engineer who founded AllEarth Renewables, said Sanders took bold steps to address climate change when former President George W. Bush was in office.

Over the years, Sanders has asked Blittersdorf, who has been involved in developing wind and solar energy for four decades, for his opinion on policy questions.

In 2007, Sanders brought Blittersdorf to Washington D.C., to testify in the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee on how “taking measures to reverse global warming can, in the process, create a new sector of the economy known as ‘green jobs.’ ”

“Bernie really has always gotten it,” Blittersdorf said. “He’s been there I think more strongly than three-quarters of our environmental organizations,” he added.

Pollina sees Sanders’ $16 trillion plan to combat climate change as a logical extension of his evolution as an economic and environmental thinker.

“Bernie has been more and more willing over time to focus attention on the idea of having to protect the environment and realizing its connection to the economy and people’s lifestyles,” Pollina said.

“Economic issues and environmental issues coming together, from my point of view as well as his,” he added.