[F]or Sen. Patrick Leahy, the effects of war don’t end when the bullets stop flying.

That’s why the longtime senator has fought for humanitarian causes long after the conflict is over — work that has resulted in the clearing of landmines in Laos, the deliverance of grievance payments to victims of the war in Iraq, and the easing of tensions with Cuba.

Now, Leahy wants to get rid of one of the most pernicious weapons ever used in conflict: Agent Orange.

During the Vietnam War, the Department of Defense devised Operation Ranch Hand, a plan to decimate the country’s agriculture and kill its vegetation. Over nine years, aerial sorties dropped nearly 20 million gallons of Agent Orange and other chemicals over Vietnam and its people. The motto of the so-called “ranch handers” was “only you can prevent a forest,” a cruel twist on the famous Smokey the Bear line about fire prevention.

Now, more than 40 years after the war ended, the public health impacts of this mission are still being felt. The Vietnamese Red Cross estimates that 1 million people have suffered health problems from this poisoning by plane, including serious birth defects and rare cancers. Many thousands more of American veterans have suffered severe health complications because of first-hand exposure to Agent Orange.

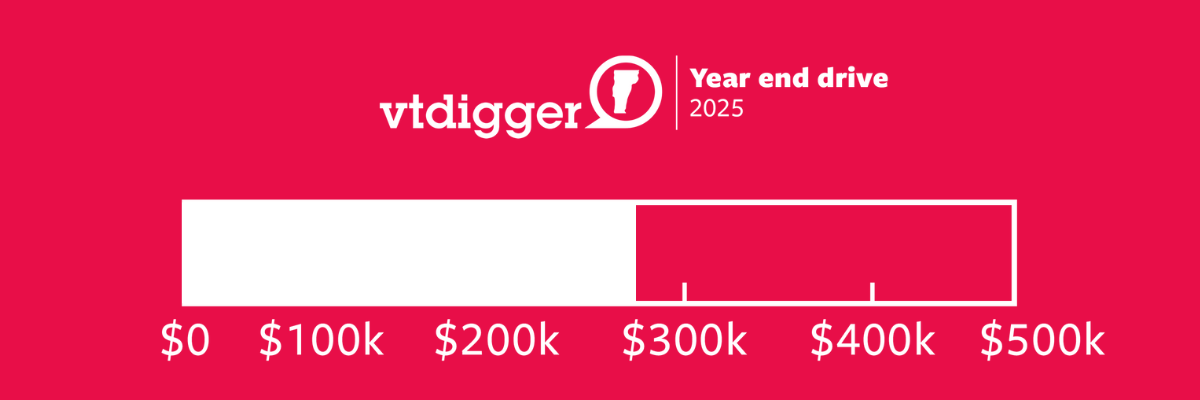

In late April, Leahy led a delegation of eight other lawmakers for a ceremony at the Bien Hoa Air Base near Ho Chi Minh City. There, Leahy helped launch a 10-year, $183 million initiative to clean up dioxin, a key ingredient in Agent Orange, in and around the airport. During the war, Bien Hoa became the largest U.S. military base and was a major storage depot of the toxic herbicide. This subsequent cleanup project is considered one of the largest chemical remediation projects in world history.

“For me, there can be no excusing the folly of that war, nor diminishing of the immense destruction and suffering that it caused,” Leahy told diplomats and citizens in prepared remarks. “But we can decide what we want the future to be, and the work we begin here today is part of doing that.”

The Bien Hoa ceremony also included the signing of a five-year commitment wherein the American government will support health and disability programs in seven Vietnamese provinces that were heavily sprayed with Agent Orange.

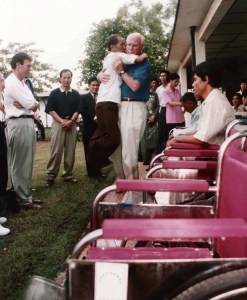

Leahy has long led efforts to help address the military damage caused in Vietnam, and he received a hero’s welcome during the Bien Hoa ceremony. In front of a wall adorned with fresh flowers, Leahy was greeted by young children and government officials. One man presented Vermont’s senior senator with a hand-drawn portrait.

One of the trip’s participants, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., lived in Vietnam for parts of 1972 and 1973 with his father, who was then deputy ambassador to the country. In an interview, Whitehouse described the reconciliation between the two countries since that conflict as a staggering diplomatic achievement.

“It is astonishing that two countries which, in living memory, fought such a difficult war should have the relationship that we have now,” Whitehouse said. “It’s always a bit of wonderment to travel there, and be a witness to that relationship. It meant a lot to be traveling on this occasion with Sen. Leahy, because one of the key vectors of our reconciliation was his work to help the victims of Agent Orange contamination and clean up unexploded ordinances.”

Leahy, who won his first Senate race during the tail end of the war, was similarly overcome with hope at what the ceremony represented. “It was emotional for me in the sense that it showed you can make a new world. Instead of bitter enemies, we are now friends.”

Leahy, the lead Senate Democrat on the Appropriations Committee, has been attracting bipartisan budget support for Vietnam for years, but this project required additional buy-in from top military brass. Over the last year or so, Leahy spoke about the need to clean up Bien Hoa with former Defense Secretary James Mattis, as well as Gen. Joseph Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and, like Leahy, an alumnus St. Michael’s College. In the end, the Pentagon backed the project unequivocally.

Leahy staffers believe the Bien Hoa project represents the first time in modern American history that the Defense Department has tacitly acknowledged its own careless damage in battle, and supported efforts to bring healing to those hurt.

Leahy’s Agent Orange cleanup efforts ramped up under the Obama administration, but a senior Leahy staffer said there was “stiff resistance” from White House and Pentagon lawyers who were worried the project would set a dangerous precedent. “Their position was, ‘We don’t want to start down this road because then everyone is going to knock on our door and ask us to make good on damage done,’ ” the staffer said.

Yet these cleanup efforts have helped strengthen partnerships with Vietnam’s Ministry of National Defense on regional security issues. Moreover, this cooperation has allowed for the remains of American soldiers to be returned home

The ambitious Bien Hoa project follows a more modest six-year, $110 million remediation effort project at the Da Nang Airport, which kicked off in 2014 and wrapped up last year.

Both projects came out of the U.S. Agency for International Development in conjunction with Vietnam’s defense ministry. The work is complex and grueling, and involves heating up hundreds of thousands of meters of soil and sediment to 635 degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature at which dioxin is neutralized.

With Da Nang cleared, thousands of airport neighbors no longer face immediate health risks and the airport’s functionality has expanded. Last year, the APEC summit was held in Da Nang for the first time, and President Donald Trump landed Air Force One on the airport’s runway, which would have been impossible just a few years ago.

Long a skeptic on Vietnam War

Leahy’s involvement in the country extends back decades, and one of his first actions in the U.S. Senate was a consequential vote to end financial support for the Vietnam War.

Within weeks of his swearing in, on April 17, 1975, Leahy, then the most junior member of Senate Armed Services Committee, cast the deciding vote in the panel to cut off funding for the Vietnam War.

The vote took place 13 days before the fall of Saigon, and President Gerald Ford asked Congress for $722 million to help support the South Vietnamese army in its battle against the North Vietnam army and the Viet Cong. Leahy said he received personal cajoling from Ford, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and Free Press Editorial Page Editor Franklin B. Smith, but his skepticism was deep-rooted.

“I heard what the generals were saying, but I read the Pentagon Papers, I heard from Vermonters coming home, and I thought the war was not justified,” Leahy said. “It was a colossal mistake.”

In a committee hearing before the vote, Leahy said, “Americans could be out of [Vietnam] within a couple of days and with a minimum of trouble and I think that that is the direction this country should take.”

“I personally, and I realize this is not necessarily the feelings of the majority of the committee, I personally would then not give any further money to South Vietnam for military purposes,” he added. Congress then took no action despite Ford’s request, and American soldiers were evacuated from the country shortly thereafter.

Leahy’s vote represented a shift in Vermont’s thinking on the war. While Leahy’s immediate predecessor, Republican George Aiken, had expressed misgivings about America’s military involvement in Southeast Asia, he was also fearful of creeping communism via China, and repeatedly voted in support of the war.

“I’m the only Vermonter who ever voted against the war in Vietnam,” Leahy said in an interview. “When I ran in 1974, the Burlington Free Press, which, at that time was a much larger newspaper, supported the war in Vietnam. The House and Senate members from Vermont had voted for the war. I said I was against it, and was told I’d never be elected.”

Leahy’s class of lawmakers was decidedly anti-war. Not only did Congress reject Ford’s request for aid to South Vietnam, they later restricted funds for other Cold War skirmishes.

Personal trust established

In 1989, Leahy and former Republican President George H. W. Bush discussed the need to initiate efforts to repair relationships frayed or altogether destroyed by these conflicts.

In 1990, Congress established the Leahy War Victims Fund, which has supported the safe removal of millions of unexploded landmines in Laos left over from the Cold War. The fund has also provided prosthetics, wheelchairs and other assistance to thousands of landmine victims.

Since Bush, politicians of all stripes have supported the Leahy War Victims Fund. In 2015, when President Obama became the first American president to visit Laos, stopped by a prosthetics clinic funded through Leahy’s efforts. On this same trip, Obama pledged a historic three-year commitment of $90 million to the fund.

Leahy’s landmine work established a personal trust with Vietnamese officials, and helped lay the groundwork for the 1995 reinstatement of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Vietnamese Ambassador Ha Kim Ngoc said in an interview he recalled the establishment of the War Victims Fund during his early years at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In the mid-1990s Leahy and his wife, Marcelle, a nurse by trade, visited Vietnam to be briefed on the work of fund. It was on this trip that Leahy lifted up slight man who used a wheelchair and kissed him. Ngoc said this trip demonstrated Leahy’s “profound sympathy for the suffering of the war victims in Vietnam.”

In conversations during and after this trip, Leahy recalled that Vietnamese officials frequently brought up Agent Orange poisoning as another devastating and lingering impact of America’s military involvement in the region. In response, Leahy sought to act, both in Vietnam and domestically.

Leahy has also secured funding for the VA’s fledgling burn pit registry, which could lay the groundwork for post-9/11 veterans exposed to the toxic smoke to receive compensation. (In May, the Vermont Legislature passed legislation to increase awareness about burn pit exposure, which a number of Vermont guardsmen believe made them sick.)

In 1991, Leahy co-sponsored the Agent Orange Act, which first recognized the adverse health consequences of Vietnam veterans exposed to the substance, and directed the Veterans Affairs Secretary to issue regulations over benefit-eligibility for sick vets. The final regulations were seen by many as overly narrow, and left many veterans, including so-called Blue Water Navy veterans, in the lurch. While Leahy supported efforts to make eligible veterans who “served in the territorial seas” of Vietnam, he opposed a 2017 effort to fund these veterans’ Agent Orange benefits, arguing the payment source, foreign visa fees, didn’t make sense. (In January, a judge ruled that the Department of Veterans Affairs must compensate these Blue Water veterans.)

Ambassador Ngoc said his country hopes to continue working with Leahy on remediating other dioxin hot spots, including at Phu Cat airport on the country’s southeast coast, removing more mines from provinces throughout the country, and continuing to provide information on Vietnamese soldiers still missing in action.

“Senator Leahy brought to Vietnam a new image of the United States, a country with compassion, ready to take moral responsibility and contribute to resolving the war legacies,” Ngoc said. “This is especially meaningful after a devastating war that left heavy consequences on both sides. His contributions help heal war wounds, build mutual trust and open a new chapter in the history of our bilateral relations.”