[N]athaniel Chipman’s name rarely gets brought into the narrative of Vermont’s early days. Usually it’s all about Ethan and Ira Allen, as the architects of Vermont independence and its eventual statehood, with maybe a slight nod to Vermont’s first governor, Thomas Chittenden.

Chipman and others from the generation of settlers that followed Allen and Chittenden played vital roles in the state’s history, but if you are trying to tell the usual story of the Allens and Chittenden bravely fighting foreign foes, their presence mucks up the plot. Chipman spent much of his political career battling the Allens, Chittenden and their allies, who he saw as at best misguided and at worst self-serving.

Part of the reason Chipman gets ignored is probably because the history of 18th century Vermont is convoluted enough without him. To review: Beginning in the mid-1700s, British colonists started divvying up the territory that would become Vermont. New Hampshire and New York both claimed the right to issue land grants in the region, setting up an obvious conflict. Those whose land was initially granted by New Hampshire, like Ethan Allen and his brothers, began an effort to terrorize settlers who had gotten their land from New York, the so-called Yorkers. And the colony of New York was seeking to arrest Allen and his accomplices.

Because of his youth, Chipman was still in Connecticut when the hostilities started. He had grown up in Salisbury, and by the early 1770s was studying at Yale College. Ethan Allen had been on a similar trajectory in the 1750s, when he studied with a minister in Salisbury with plans to attend Yale.

But the courses of their lives diverged, wrote historians Sam Hand and Jeffrey Potash in their 1991 essay, “Nathaniel Chipman: Vermont’s Forgotten Founder.” Allen never attended college. His father died prematurely in 1755, forcing Allen, who was still a teenager, to take responsibility for his family’s well-being. After a series of failed business ventures, he struck off for the region then known as the New Hampshire Grants, and soon became the leader of the Green Mountain Boys, the armed group resisting Yorkers’ land claims.

With the outbreak of the Revolution, Allen fought the British, while maintaining his running battle against Yorkers. He led the taking of Fort Ticonderoga, then spent two years as a prisoner of war after being captured during a foolhardy attempt to capture Montreal. Released in 1778, Allen wrote a popular account of his captivity, which sold well and helped cement his image with the American public.

Chipman reached Vermont the same year Allen’s book was published, 1779. He arrived a veteran of the Continental Army, having served at Valley Forge. But his family was in financial trouble, so he requested and received his discharge. He told a friend: “I am already in debt, and a continuance in the service to me affords no other prospects than that of utter ruin.”

Chipman now had other things than service to country in mind. He crowed about his prospects. Assuming he would be the first lawyer to arrive in Vermont, he wrote, “(T)hink what a figure I shall make, when I become the oracle of law to the state of Vermont.” He was in fact the third lawyer here. But it hardly mattered: the tumult in the area meant people wanted to protect their property and turned to Chipman to do so. The steady business made Chipman prominent. Having settled in Tinmouth, he became Rutland County’s first state’s attorney and a member of the Vermont House. Later in life, he would become a U.S. senator and chief justice of the Vermont Supreme Court.

During the war, Ethan and Ira Allen, and Thomas Chittenden (who was also from Salisbury) were members of what historians refer to as the Arlington Junto, which effectively ran Vermont during the first years after it declared its independence in 1777. Members of the Junto negotiated secretly with the British governor of Canada, Gen. Frederick Haldimand, about Vermont rejoining the British Empire.

When word of the talks leaked, Chittenden asked Chipman to inform Gen. George Washington that Vermont remained loyal. Historians have debated how serious the Arlington Junto ever was about the Haldimand Negotiations. Some believe the Junto was making a brilliant political move, using the talks as a way to hold off a British invasion, while pressuring Congress to make Vermont part of the union. Others accuse Junto members of planning to sell out the colonies to protect their trading relationship with Britain.

Chipman’s cooperation with the Junto ended there. In 1784, with the Revolution over, Chipman became a state legislator and immediately challenged Chittenden’s coalition over the issue of returning land to British Loyalists. During the war, Vermont’s leadership had confiscated land from Loyalists, often giving it Junto members and their allies. Now Junto members wanted Loyalists to pay for land improvements that had been made in their absence.

Chipman argued that the land had been seized illegally and therefore the new settlers were not entitled to any compensation. A Junto ally attacked Chipman, saying he represented the interests of aristocrats (the Loyalists) over those of the common people (the new settlers). Chipman forced a compromise. Settlers would be paid, but only half the value of any improvements they had made.

Chipman was soon butting heads again with the Junto. When Chittenden appointed Ira Allen to negotiate a trade treaty with Canada, Chipman and others opposed it. Seeing the treaty as a way for Allen to protect his lumber holdings, they argued that the public should not pay for a pact whose benefits would be “partial and confined to a few individuals.”

By the mid-1780s, Vermont was in a financial crisis. British specie (hard currency) was scarce, but merchants who had bought goods using specie demanded that customers repay them in kind; they weren’t interested in paper currency that had no backing in gold or silver. Those customers, mostly farmers, found they had debts they couldn’t repay and were therefore in danger of losing their land. Mobs assembled at courthouses, threatening to stop foreclosure hearings.

Chittenden responded by pushing legislation that would allow farmers to pay debts with livestock or grain, which would be valued at an inflated rate. A separate bill would establish a state bank that could issue paper currency. Furthermore, Chittenden called for all lawsuits to be taxed.

Chipman attacked the proposal, arguing that the value of the paper currency would soon plummet in value and trigger runaway inflation that would only worsen Vermont’s economy. Some claimed the proposal would benefit large landowners like Chittenden, who could use the currency to pay off his own $3,000 debt. Chipman might also have been irked by the threat the tax posed to his legal business.

The matter was put to referendum to gauge public opinion. Chipman’s arguments won the day: Vermonters opposed Chittenden’s proposals by a four-to-one margin. Chittenden was forced to propose legislation that would allow debts to be repaid with personal property only if the creditor agreed.

At about the same time, Alexander Hamilton, a leading New York politician, tried to get New York to recognize Vermont’s independence for fear that otherwise Vermont might join Canada. The New York Assembly rejected Hamilton’s idea. Chipman later wrote Hamilton, informing him that if an accommodation could be made with New York over land titles, then Vermonters would willingly join the union.

Meanwhile, Ethan Allen continued to flirt with the idea of Vermont rejoining Britain. He informed the new governor of Canada that he needed weapons to resist the push for Vermont statehood, which he was sure was coming. Chittenden also opposed statehood and arranged for Ira Allen, another statehood opponent, to be among three Vermont delegates negotiating the issue with Congress. Ira Allen so opposed statehood that he refused the assignment.

The so-called “Woodbridge Affair” may finally have doomed efforts to keep Vermont out of the union. Chittenden was accused of doing a favor for Ira Allen, granting him title to the town of Woodbridge (current-day Highgate). Chittenden’s opponents attacked him for malfeasance and said the Allens were “making their fortunes out of the whole state.”

The affair briefly cost Chittenden his office. In 1789, he won a plurality of the vote for governor, but not a majority, so under the state Constitution, it was up to state legislators to pick the winner: They chose the runner-up, Moses Robinson, of Bennington. Chittenden regained the governorship in 1790.

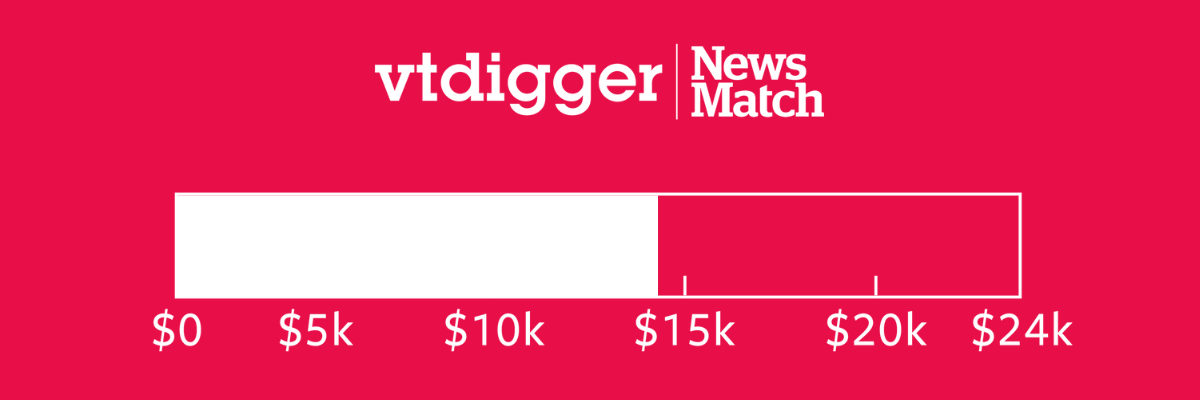

That fall, Chipman helped negotiate a settlement with New York; for $30,000, New York would drop its opposition to Vermont joining the union.

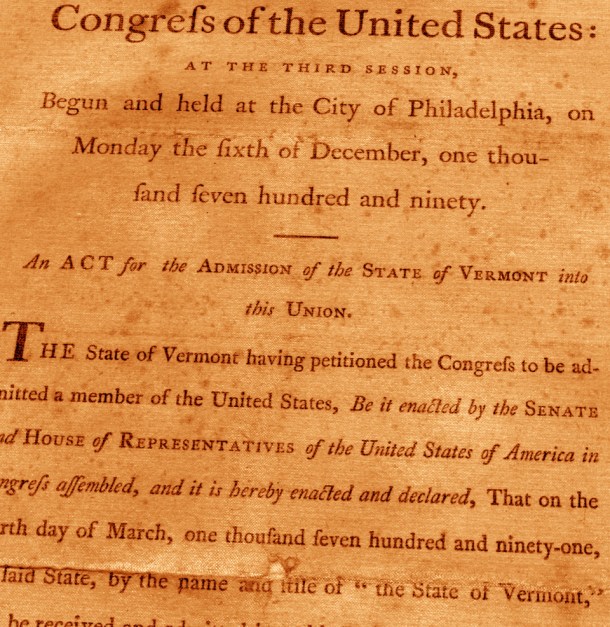

The following January, 109 delegates gathered in Bennington to ratify the U.S. Constitution, a step that would lead two months later to Vermont’s admission to the union. Among those attending were Chittenden and Ira Allen — Ethan had died two year earlier. The two men, noted Daniel Chipman in his biography of his brother Nathaniel, were “practically the only representatives of the old guard present.” A new generation of leaders, represented by men like Nathaniel Chipman, was now firmly in charge.