[T]hree years after hundreds of wells in southern Vermont were found to be contaminated with a class of chemicals linked to serious health issues, the state is set to begin a new sampling effort to determine how great of a threat PFAS poses to drinking water across Vermont.

State officials published a plan this month to test for PFAS contamination by car washes, landfills, and at all public drinking water supplies. Testing is set to begin in July.

“I really look at this statewide sampling plan as building on what we learned from the…sampling we did after discovering Bennington (contamination),” said Chuck Schwer, director of waste management and prevention for the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation.

PFAS substances gained notoriety in Vermont when the state discovered widespread PFOA contamination around two former factories in North Bennington in 2016. Over 300 private drinking water wells had PFOA levels above the state’s health advisory. The state worked with Saint-Gobain Plastics Performance, the company that had acquired the former owner of the factories, to install treatment systems and reached a multi-million settlement to cover the cost of municipal water line extensions.

Since then, the state has also found PFAS contamination in drinking water near a former wire coating facility in Pownal, by the Rutland Southern Vermont Regional Airport in Clarendon, and at the Grafton Elementary School, among other sites.

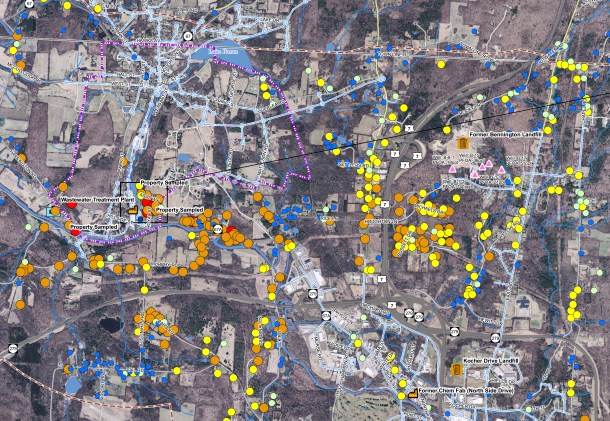

PFAS contamination in Vermont

Source: Vermont DEC; Chart by Felippe Rodrigues/VTDigger.org

PFAS do not break down in the environment and are used in a wide array of manufactured products, from rain jackets to cookware to firefighting foam. Scientists now know that exposure to certain PFAS chemicals can lead to cancer, hormone disruption, immune system damage, developmental problems in children and low birth weight.

State officials identified car washes and electroplating — a type of metal coating — facilities as high priorities for the next round of sampling, said Schwer. As Vermont has 79 car washes, state officials will prioritize testing by car washes near high numbers of private drinking water wells, he said.

This May, Gov. Phil Scott signed into law Act 21, which requires drinking supply managers to test to ensure levels of five PFAS contaminants — PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFHpA and PFNA — are below a combined 20 parts per trillion. If elevated levels are found, drinking supply managers have to treat the water to lower the levels.

While the state will not be testing public drinking water supplies, the Department of Environmental Conservation has been working with water supply managers to prepare for the Dec. 1 testing deadline, said Schwer. One of the biggest costs for the state would be installing treatment systems at drinking water supplies if elevated PFAS levels are detected, he said.

“When you think about how low our health standard is, it’s definitely got a lot of water supply owners concerned,” he said.

The state will also require additional PFAS testing of landfill leachate, wastewater treatment plant output, groundwater at landfills and treated sludge spread on fields. Casella, owner of the Coventry Landfill, is also required to test PFAS levels in certain kinds of industrial waste it receives.

Jen Duggan, director of Conservation Law Foundation Vermont, said that the state Agency of Natural Resources has taken a “leadership role” both in terms of identifying and remediating PFAS contamination. She pointed out that Vermont will be testing for 18 different types of PFAS compounds, compared to Michigan, which will only be looking at two of the most toxic compounds in its testing.

“The work that they are doing and that they are proposing to do is significant,” Duggan said of ANR’s PFAS testing.

She added, however, that CLF would like to see more of a detailed plan for the testing. CLF wrote in a public comment letter that the state has previously identified additional industries —- like paper coating plants and paint manufacturers — as possible sources of PFAS contamination that are not mentioned in the new sampling plan.

Schwer said that, based on conversations with other states and research, electroplating had stood out as a source of industrial PFAS contamination that the state had not yet investigated.

“We haven’t ruled those out,” Schwer said of other industries the state had identified. “We just haven’t had the ability to go in and look more at the history of those facilities.”

At a Senate committee meeting in April, Sen. Brian Campion, D-Bennington, asked whether the state should put a “moratorium” on sludge spreading until it has a better understanding of PFAS levels in sludge.

Sludge has to be treated to Environmental Protection Agency biosolids standards before it can be spread on fields. Some farmers apply biosolids to fields because they contain nutrients needed for plant growth and can improve soil structure, according to a report from the Department of Environmental Conservation.

Duggan said CLF does have “serious concerns” about levels of PFAS and other emerging contaminants in treated sludge spread on fields.

Schwer said ANR feels the state needs more information before it would recommend a ban.

“And I think the sampling will give us this information,” he said.

While PFOA and PFOS — two of the most toxic PFAS compounds — have been phased out by industry, they do not easily break down, so chemicals used years ago persist in the environment.

The EPA has been slow to regulate PFAS, leaving states largely on their own to figure out how to deal with contamination. Both the EPA and the White House sought to block release last summer of a federal health study on PFAS contamination, fearing it would cause a “public relations nightmare.”

The EPA has set a non-binding health advisory for drinking water at 70 parts per trillion, although the head of the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences recently said many experts think that is too high. Vermont is one of seven states that is moving ahead with setting a lower drinking water standard.

“It would have been really wonderful for the EPA to have taken the lead and answered a lot of the questions that we all are indeed having, but that’s not happening with today’s EPA,” said Schwer.