At least in public, Bernie Sanders does not sing much these days. But more than 30 years ago, he recorded five songs on a record album, and his choices might offer some insight into a political problem facing his presidential campaign.

It was (no surprise) a decidedly left-wing selection: “The Banks of Marble” (whose “vaults were filled with silver the workers sweated for”), the peace anthem “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” Woody Guthrie’s populist/patriotic “This Land is Your Land.”

And two civil rights songs: “Oh, Freedom,” and “We Shall Overcome.”

Nobody knows who wrote those songs. “Oh Freedom” was associated with Odetta, but also with Joan Baez. “We Shall Overcome” was polished and popularized by Pete Seeger, who introduced it to Martin Luther King Jr. in 1957.

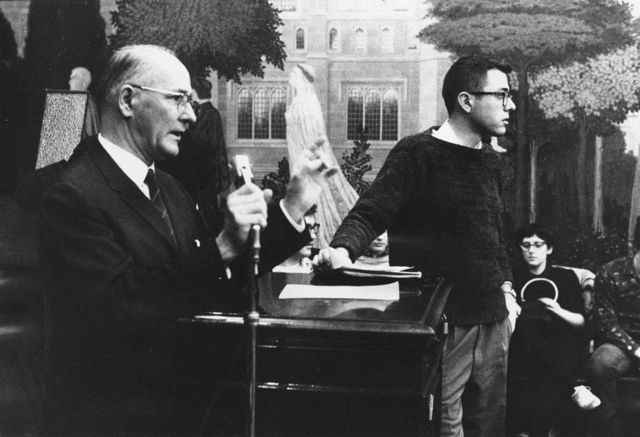

They were black and white together, just like the line in another song Sanders and his friends sang at the University of Chicago in the early 1960s, when he was a civil rights activist.

“We are black and white together,” the song declared, and “like a tree that’s standing by the water, we shall not be moved.”

Bernie Sanders has not changed much. Like a firmly planted tree, he is as committed to racial equality as he was when he was arrested in anti-segregation protests.

That’s not a problem. What may be a problem is that he is committed to it in the same way that he was in the ’60s, when to be for racial equality was to be for racial integration.

For Sanders, the problem is that at least in some factions of the political left – mostly but not entirely on college campuses – a neo-segregationist viewpoint has replaced the “black and white together” approach of the past.

This is intellectual and cultural segregation; no one has proposed separate water fountains. Even the one-race-at-a-time “safe spaces” only for black students (and now some only for white students) are intended as temporary refuges, not permanent policy.

Less temporary is the inclination to divide people – and to encourage them to divide themselves – into “identities” by race, gender, sexual orientation, and more. “Citizen” is rarely one of the identity options.

All politics has always included appeals to identity. People tend to vote for the candidate they think is “one of them.” But until recently that connection extended to region, occupation, and class, not just race, gender and sexuality.

Nor is identity politics confined to the left. No one has practiced it more blatantly or more successfully than President Donald Trump, who got elected and continues to campaign by conflating American-ness with non-Hispanic whiteness.

But identity politics is more open and more visible on the left, even the center-left. Rare would be the Democratic candidate for any office today who would dare say, “there’s not a black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America; there’s the United States of America.”

That was Barack Obama, 2004. It’s what made him president. By the end of his term it was getting him ridiculed in “The Root,” a black-oriented online magazine.

When Bernie Sanders expresses doubts about identity politics, he gets ridiculed and then some. When he said in January that some Democrats “think that all that we need is … candidates who are black … or Latino or woman or gay, regardless of what they stand for,” one left-of-center commentator said Sanders had “a long history of … excusing racism.”

The years of Sanders’ youth and young adulthood were a time “when literature mattered,” in the words of “Facing the Abyss: American Literature and Culture in the 1940s” by Cornell University Professor of American Culture George Hutchinson (Columbia University Press 2018).

Many of the creators of that literature were black, female, Jewish, or gay. But they saw themselves, Hutchinson says, as exploring “the human condition” more than their tribal identity. Theirs was “a universalist framework” that sought to “transform American culture,” which belonged to all of them. White novelists wrote about black people and blacks wrote about whites. They praised one another and influenced one another.

“There is one race and … we are all part of it,” wrote the often militant black novelist and essayist James Baldwin.

Contrast that with a practice in the world of fiction-writing today. Publishers of young adult novels hire “sensitivity readers” to make sure that nothing seems offensive to any “identity.” To avoid possible offense, some publishers encourage an “#ownvoices” policy, in which a book’s main characters have to share the author’s race, gender, and sexuality.

It’s hard to know how widespread are the forces of neo-segregation. Young African-Americans and Hispanics continue to enlist in the armed services in numbers corresponding to their share of the population. For the economic opportunity, of course, but it’s unlikely that people would join the United States armed forces if they did not feel a connection to the nation as a whole.

And every day black, white, Hispanic and Asian people work together, play together, dine together and increasingly (if still not commonly) go out on dates and marry one another. Maybe it’s only the (self-anointed?) intellectual elites on campus, at publishing houses and in magazine offices who are obsessed with “identity.”

But maybe not. Pursuing racial equality the old-fashioned, integrationist, way hasn’t worked yet, so perhaps some people of all races have decided to try it another way.

Besides, identity-mania can be found in the mainstream. On CNN the other night, three analysts held a lengthy discussion (the transcript takes up five pages) about whether California Sen. Kamala Harris was “black enough,” and even if she is, as the daughter of a black man raised in Jamaica, does she qualify as African-American?

Not a word about the wisdom of her public policy proposals. Not a word about whether her hue or ancestry had anything to do with whether she’d be a good president. It was all identity all the way down.

One reason Sanders lost the 2016 nomination was that Hillary Clinton beat him badly among African-American primary voters. He’ll have to do better this year, even with two black candidates, Harris and New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, in the race.

He’s trying. He has a more diverse staff. He acknowledges that “identity is important” and talks of the need to “end all forms of racism in this country.”

But he gets more animated when discussing income inequality, the plight of the low-income of all races, the predations of the ultra-rich. His campaign slogan is. “Not me. Us.” As in all of us, together, unmoved like that tree standing by the water.

At a certain stage, it’s hard to stop singing the songs you learned when you were young, especially when those songs are so good.