[A]n AT&T executive told Vermont senators a few weeks ago that the company’s cell service covered 94.4 percent of the state as of November 2017.

That contrasts sharply with a state drive test conducted last year, which found that calls can reliably be made on AT&T’s network on about 64 percent of Vermont’s highways, which is skewed toward populated areas with commercial coverage.

And the company’s assertion of 94.4 percent statewide reach is even further away from an independent consultant’s report that put AT&T’s coverage at just 31 percent of the state in 2017, using the company’s own data.

This raises the question: Was Owen Smith, AT&T’s New England regional vice president, misleading Vermont lawmakers when he submitted written testimony last month saying the company was already close to 95 percent coverage?

In a footnote to that figure, the company concedes that its “numbers may be overstated” in some areas due to the limited samples it uses to measure coverage. So how does the company measure coverage, exactly? An AT&T spokesperson said on Saturday and Monday that that information was not readily available.

“Those maps are not credible,” Corey Chase, a telecommunications analyst for Vermont’s Department of Public Service, said of the coverage maps that AT&T and other companies submit to regulators.

Chase carried out the drive test on hundreds of miles of the state’s highways, taking 187,506 download speed tests along the way.

“I think it’s pretty plain to everybody that the emperor’s not wearing clothes,” he added. “Anyone who has driven around the state, you know there’s no cellphone coverage but when you look at that map it shows there is.”

This has raised questions about what, exactly, Vermont can expect from AT&T when it finishes a five-year project called FirstNet, an ambitious federally funded effort to build a nearly universal network for first responders. AT&T claims the network will cover 99.9 percent of the country, and 99.9 percent of each state.

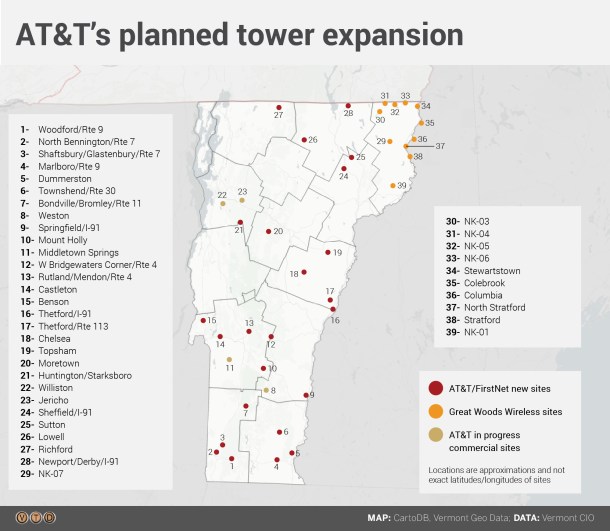

The 36 towers slated to be built in Vermont over the next three years will also be used for AT&T’s commercial customers, which has led lawmakers to ask whether FirstNet might be the solution Vermont has been looking for to fill rural coverage gaps.

But will the company’s 99.9 percent coverage claim in a few years have any more credibility than its 94.4 percent claim today?

“I think coverage means a lot of different things to different people,” said Chase.

As a national standard, the Federal Communications Commission says all Americans should have access to 4G LTE at a speed of at least 5 megabits per second. Chase drove around the state last year with an array of phones to find out which companies were hitting that mark.

AT&T only delivered speeds at or above the 5 Mbps threshold on 25 percent of highways in the state (compared to 35 percent for Verizon and 22 percent for T-Mobile), according to Chase’s tests.

If the threshold for “coverage” is lowered to simply being able to make a voice call, which requires speeds faster than 256 kilobits per second, AT&T covers 64 percent of highways (compared to 67 percent for Verizon and 52 percent for T-Mobile).

Asked what Vermont can expect in a few years, when FirstNet is complete, an AT&T spokesperson wrote: “The mission of FirstNet is to help ensure wherever public safety goes to respond to an emergency, they have the connectivity and communications they need.”

All about the money

Whether Vermont’s policymakers believe AT&T’s claims or not, the FirstNet buildout might be their best hope at making significant strides in wireless broadband coverage in the next few years, at least until more federal grants arrive.

Senate Finance Chair Ann Cummings, D-Washington, joked earlier this winter that she figured out why universal cell coverage was so elusive: It’s going to cost hundreds of millions of dollars, yet the state is putting less than $1 million toward the effort annually.

“You certainly can’t write your way out of this problem,” Clay Purvis, telecommunications director at the Department of Public Service, said during a recent interview. “You can’t write a recipe book that will give us broadband.”

AT&T won a $6.5 billion contract with the federal government to build out FirstNet nationwide, but is also intends to use those towers for its own commercial network. Vermont decided to let AT&T build out the state network instead of using $25 million in federal and dedicated broadband spectrum to do it itself.

“We’re going to places it wasn’t commercially feasible for us to go,” Smith, the AT&T executive, told state senators last month. “The business case wasn’t there; now that we have FirstNet, we’ve committed to going out to the rural areas and expanding our network.”

Smith added that once AT&T pays for the towers to be built, they are owned by a third party, so other companies can come behind them and expand their own networks.

But AT&T won’t tell state officials almost anything about its plans for FirstNet, claiming that the information is proprietary. It won’t say where the towers are being built, when they will be finished, where gaps will be in two years, in five years.

The state has tried to fill the gaps on its own. The last time it tried — a joint “microcell” project with the private firm CoverageCo — was a $4 million failure. As state officials try to regroup, the secrecy of FirstNet is raising many questions.

Is it worth investing in a new, state-run solution? Should investment focus on areas where FirstNet will not reach? If so, where? And if AT&T’s claims that it will reach 99.9 percent of the state in three years are true, does Vermont just need a stop-gap solution?

These all remain open questions, though lawmakers and advocates note that dozens of communities are without cell coverage amid the search for answers.

‘Devil’s in the details’

Before Gov. Phil Scott decided to opt in to the FirstNet contract in 2017, the state hired two consultancies to analyze what the state was signing up for.

The resulting reports, which are confidential and more than a year old at this point, describe AT&T’s plan in far more detail than the company has been willing to share publicly since the contract was signed.

“This proposed buildout, including the addition of 39 new sites, is predicted to serve 76% of the land area of the state,” and could go as high as 81 percent by 2022, independent consultant Televate wrote in October 2017. That estimate included four “in progress” commercial sites being built by AT&T.

Televate’s estimate of AT&T’s current coverage was more in line with Chase’s findings in his drive test, which found that just a quarter of the state had 4G LTE broadband coverage at speeds that would enable web browsing or limited video streaming. Televate estimated 2017 coverage at 31 percent, noting that AT&T’s own projections do not meet the typical standards for public safety communications.

Terry LaValley, the state’s “single point of contact” for FirstNet as chair of the Public Safety Broadband Commission, said the Televate report, dated Oct. 30, 2017, is based on outdated information. He said another tower has been added — now 36 in total for FirstNet alone — and AT&T’s commercial buildout plans have changed.

“The projections that are indicated in that report do not reflect what we expect to see today,” he said. LaValley now expects something close to 95 percent coverage when FirstNet is complete.

“What coverage actually means to the user is where the devil’s in the details,” he added. “We may say you have 99 percent, but you may only have one bar on your phone.”

LaValley added that he and other officials are working with AT&T to more clearly define what sort of coverage emergency responders will have when FirstNet is complete. AT&T also says it will make at least one mobile truck-mounted cell tower available to plug gaps when they arise.

The Televate report said coverage gaps would remain in the following places:

– Franklin County: Coverage is still required around Enosburg

– Orleans County: Coverage hole persists in the southeast of Barton and the northeast corner

near the Canadian border

– Orange County: Coverage gaps between Chelsea and Haverhill, New Hampshire

– Windsor County: Between Goshen and Rochester

– Bennington County: Gaps near Sandgate

It’s unclear if those gaps will remain based on FirstNet’s current plans. Both Smith of AT&T and Chris Herrick, deputy public safety commissioner, offered to talk to individual senators about coverage in their constituencies, but said they would not have those conversations in a public setting. Smith did not respond to emailed questions.

Herrick, along with LaValley, is among a handful of officials given quarterly updates on FirstNet’s work in Vermont. But Herrick said he’s not even allowed to take maps or operational information out of meetings.

The leak of the confidential reports about FirstNet in late 2017 sent Agency of Digital Services Secretary John Quinn into a tizzy. He went so far as threatening to get the attorney general involved in investigating who released AT&T’s intellectual property.

One of the reports, by Coeur Business Group, a technology consultancy, details the risks of “opting in” to AT&T’s FirstNet plan, as opposed to the state building and managing its own network.

“Without a documented disaster plan and especially an escalation plan for outages, the state will be exposed to non-availability without authority to properly manage the vendor,” the report says.

Another concern: it’s up to the federal government to penalize AT&T if it misses its targets, “but Vermont doesn’t have the specifics surrounding those penalties, nor does it appear that Vermont will be provided any concessions/penalties from FirstNet, or AT&T if timelines are missed.”

It adds: “There is also a concern that Vermont’s state specific requirements and desire to partner with AT&T could be drowned out by the states with larger population centers.”

Stephen Whitaker, a volunteer public advocate on technology issues, sent unredacted versions of the reports to senators this year. The documents were forwarded to VTDigger, which confirmed authenticity of aspects of the reports with sources familiar with the FirstNet plans.

Whitaker has pointed out that, among other things, the reports highlight the risks and drawbacks of the FirstNet arrangement, which means state officials can’t plead ignorance if something goes wrong.

He accuses AT&T of backing away from some of its initial commitments regarding the quality and speeds of the FirstNet network. And he has called on the state to do a better job of integrating FirstNet planning into all of its other telecoms programs, such as microcells, 911 networks and emergency dispatch.

“In so doing, we need to identify whatever slim means of accountability remain available to the State for this 25-year FirstNet contract where the State is not a party to the contract nor is the contract available for review,” Whitaker wrote to senators last month.

Sen. Randy Brock, R-Franklin, asked Smith about worst-case scenarios during a Senate Finance Committee hearing on Feb. 5.

“In the event, not that I anticipate this happening by any means, if there was a catastrophic failure to deliver to the extent that has been promised, does the state have any recourse against FirstNet or AT&T?” Brock asked.

“Good question,” Smith responded, “and I don’t have an answer.”