Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

[W]e know this much about Justin Morgan: he had a horse. And that horse sired a much-loved equestrian line that took Morgan’s name and eventually became the Vermont state animal. What we usually ignore is where this man and this horse came from. We know something about Morgan – he left court records and descendants behind – but the picture we can draw from them is faint. We know still less about the horse.

So, let’s start with the man. Morgan was born into a poor family in West Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1747. Despite the family’s poverty, he received a fair amount of education. He had good penmanship and taught himself how to read, write and play music. He is frequently described as being tall and slender, his thinness the apparent result of tuberculosis he contracted as a young man. The ailment made him ill-suited for the life of a farmer. Most historians suggest it was his physical condition, more than personal interest, that persuaded Morgan to become a schoolmaster.

But he had other pursuits, too. If it hadn’t been for his horse, Morgan would still have gained some renown for his music. Indeed, his psalms were some of the most popular of his generation. However, his songs, including “Amanda,” “Huntington” and “Montgomery,” didn’t wear well. They were included in collections of great American psalms and hymns published in the late 18th century, but were soon forgotten when tastes changed.

Not until he was 31 is there any evidence of his most famous interest: breeding horses. That year, 1778, he advertised the services of his stallion Sportsman in the Connecticut Courant. The cost was “$8 the season, and four the single leap.” Interested parties were to bring their mares to Morgan’s West Springfield stable.

Morgan was ensconced in his hometown, having bought seven acres from his brother that were adjacent to their father’s land. Many of Morgan’s relatives lived around Springfield (including a cousin whose descendent would be financier J.P. Morgan). Another of Morgan’s relatives was Martha Day, a first cousin, whom he would marry.

The American Revolution brought turmoil to Massachusetts. What effect it had on Morgan is unknown. We do know that he didn’t serve on either side in the fight, perhaps due to his frailness.

He also seems to have played no part in the regional rebellion that followed. In 1786 and 1787, an armed uprising of farmers, led by Revolutionary War veterans, raged in Western Massachusetts. The farmers were saddled with debts and high taxes – ironically, to pay off the war many of them had helped win – and faced forfeiture of their land.

The revolt, known as Shays’ Rebellion for one of its leaders, coincided with an economic crash, which hit Morgan and his neighbors. That depression, theorizes Vermont researcher Betty Bandel in her biography “Sing the Lord’s Song in a Strange Land,” may have persuaded Morgan to try his luck elsewhere. Another reason Morgan moved to Vermont, suggests Bandel, was that townspeople had entrusted him with the unenviable job of tax collector in his part of West Springfield. Under state law, if a tax collector failed to collect all the taxes owed by his neighbors, he had to make up the shortfall. Town records for 1788 show that Morgan’s collection had come up short.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Justin and Martha Morgan chose that year to bring their family north. Joining the Morgans as new Vermonters were many of the leaders of the rebellion, fleeing from authorities. The influx from Massachusetts caused Mary Palmer Tyler, wife of playwright and future Vermont Chief Justice Royall Tyler, to comment that Vermont was thought of as “the outskirts of creation by many, and where all the rogues and runaways congregated.”

Justin Morgan soon became a fixture in his adopted town of Randolph. In 1789, he was elected lister. The next year, he became town clerk.

The Morgans had three children when they arrived in Vermont. Two more daughters soon followed. When the second was born in 1791, Martha Morgan suffered complications from the delivery and died 10 days later at the age of 37.

Martha’s death devastated the Morgan household. Unable to cope, Justin Morgan eventually decided to send his four youngest children to live with neighbors. The year Martha died, he composed a song based on a poem by Alexander Pope and entitled it “Despair.”

Morgan continued his work as a schoolteacher, singing master and horse breeder.

The year after Martha’s death, Morgan returned briefly to Massachusetts to collect on an old debt. Here’s where the horse comes in. In lieu of cash, Morgan accepted a pair of horses, a gelding and a promising-looking three-year-old bay colt named Figure.

Morgan advertised Figure’s stud services in the spring of 1793 in a Windsor newspaper, Spooner’s Vermont Journal. The horse would divide the breeding season between a stable in Randolph and one in Lebanon, New Hampshire. “Said horse’s beauty, strength, and activity, the subscriber flatters himself the curious will be best satisfied to come and see,” Morgan wrote.

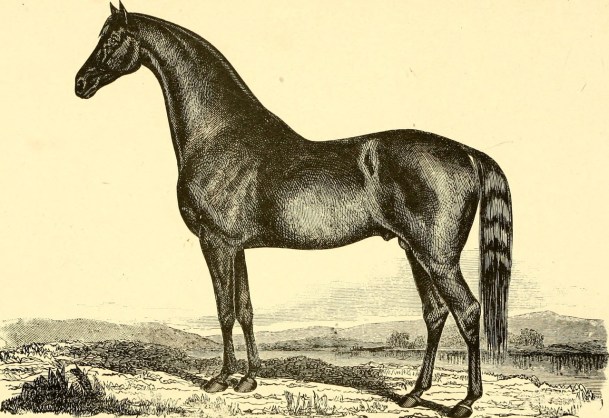

Figure – who, during his lifetime, became known as “Justin Morgan’s Horse” – proved a fantastically versatile horse. Like the famed line that would follow in his hoof prints, Figure could pull tree stumps, plows or wagons as easily as win races and pulling competitions. Though not a large horse, he was strong and fast and, not insignificantly, mild-tempered. In short, Figure had all the traits that would make generations of Morgan horses beloved among farmers, cavalry soldiers and competitive equestrians. Morgan lineages would also influence major breeds of American horses, including the American Quarter Horse, the Standardbred and the Tennessee Walking Horse, as well as England’s Hackney horse.

Figure’s own ancestry has been much debated, and little resolved. Records about the mare that bore Figure are scant, other than that she belonged to Morgan. In horse breeding, the traits of the stallion are key, because they can sire many foals in a season while a mare can only birth one or two. Therefore, breeders look for stallions with the desired traits, particularly “prepotency,” the ability to pass on more of his genes to offspring than the mare.

The stallion that sired Figure is widely believed to have been a horse known both as True Briton or Beautiful Bay. If that’s the case, then Morgan would have known what he was getting in Figure. True Briton belonged to a woman Morgan knew and he had kept the horse at stud for her during his Massachusetts days.

True Briton came with an interesting story. He was said to have belonged to a British colonel in the Westchester Light Horse brigade during the Revolution. One day, American scouts, spotting True Briton standing unguarded in White Plains, New York, stole him and sold him.

What type of horse Figure was is a bit of a mystery. Of course, there was no such thing as a Morgan when he was born. True Briton is said to have been an English horse, or Thoroughbred. Morgan’s son remembered his father saying Figure was a Dutch horse. Another theory is that Morgan horses descended from horses sent to the New World by Louis XIV, which today are called Canadian horses.

Wherever Figure got his traits, he passed them on to numerous sons and daughters, who in turn produced the Morgans that proved so well adapted to New England farming.

Figure lived for 32 years. He spent only four of those years as Justin Morgan’s horse. Morgan sold Figure in 1795 or ’96 to Samuel Allen of Williston. Why would Morgan part with such a fine horse? Bandel speculates that Morgan felt his health slipping and wanted to secure an inheritance for his children. He apparently traded Figure for 100 acres in Moretown, which he must have thought was a safer investment to pass on to his children. Figure might have been a great horse, but he was still mortal. Morgan’s own healthy continued to decline and he died in 1798, a poor, if not destitute, man.

Figure knew several owners after Morgan. He belonged to Allen for only a year before being sold to a man from Montpelier. Figure lived until 1821, spending his days at stables around Vermont and in the Upper Connecticut River Valley of New Hampshire. He met his end in a scrape with another horse, which kicked him. Figure died of his injuries and is buried in Chelsea. By the time he died, his offspring were among the most celebrated workhorses and racehorses in New England.

Still, Figure’s legacy wasn’t secure. In the 1840s, breeders in Vermont and western New Hampshire feared that if they didn’t act that the special traits of Figure and his descendants might become diluted. So they tracked down the second-, third- and fourth-generation descendants of Figure, bred them and secured the future of a Vermont icon.