Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

Tipping points in history aren’t always the sudden, dramatic events we might imagine. It doesn’t take the rise and fall of leaders, the outbreak of war, or a natural disaster to change the course of history. Sometimes the tipping point can be something seemingly mundane.

Vermont experienced such a change during the mid-1900s when companies, in an effort to cut their costs, began promoting a simple new technology that ended up transforming the state’s rural economy and landscape.

The Vermont of the early 1950s was markedly different from the state we know today. In 1953, Vermont boasted nearly 11,000 dairy farms, which formed the backbone of the state’s rural communities.

The reason the state could accommodate so many farms was that most were small, family operations. The average Vermont herd had only 25 dairy cows. But by 1963, one-third of those farms had closed. By 1970, the number had been cut by nearly two-thirds. And today, the state is home to fewer than 1,000 dairy farms — less than 10 percent of the total it had in 1953.

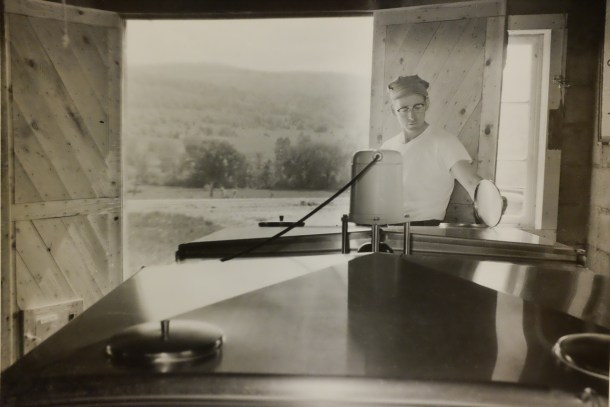

Over the years, a variety of factors contributed to this precipitous decline, but the one that started the plunge was the mandated adoption of a machine that chilled large quantities of milk on farms. Beginning in 1952, milk handlers from Massachusetts and Vermont began pushing farmers to install stainless steel bulk tanks. The new tanks made it easier for the handlers to collect milk, thereby cutting their costs. The cost of the shiny new tanks, however, was borne by farmers. Or in thousands of instances, not borne by farmers who instead went out of business, having decided the investment was too expensive.

Vermont State Archives

The move to bulk tanks didn’t happen in isolation. Until the late 1800s, much of Vermont’s milk supply was processed by the state’s numerous local dairy cooperatives and factories into butter and cheese. These less-perishable products could be shipped to distant markets.

But the dairy industry changed in 1890, when the first rail shipments of Vermont milk left Bellows Falls headed for Boston. Railroads, and the advent of refrigerated rail cars, gave Vermont dairy farmers access to the Northeast’s growing market for fluid milk, but this arrangement also tied them to an increasingly competitive market.

So it was that starting in the 1950s, when milk handlers saw that bulk tanks could reduce their costs, they urged and eventually required farmers to use them. This was solely an industry mandate. The state government’s only involvement was issuing and enforcing sanitary regulations regarding the tanks.

Before bulk tanks, farmers had relied on 10-gallon metal cans to store milk. The process was labor intensive. Farmers would milk their cows by hand or by machine into pails. They would then carry the pails to the milk house, which was usually attached to the barn, where they would pour the milk through a strainer into one of the cans. Once a can was full, the farmer would put it into a cooler. If the farm didn’t have electricity, the cooler was typically chilled with ice that had been cut during the winter and stored in straw or sawdust.

Farmers would deliver the milk cans to the creamery themselves, said Don George, a former head of the state’s Dairy Division, in a 1988 interview. One of the benefits of this system, George said, was that “this was the way the farmer communicated with all of his neighboring farmers. … There was a lot of chitchat that went on about dairy farming and other things.” But it was time consuming for farmers to wait their turn to unload their milk. Despite the community cohesion this socializing instilled, as farms got larger, farmers increasingly decided they couldn’t afford the time, so they hired others to deliver the milk. Later, George said, creameries began picking up milk cans from the farms.

By 1955, many Vermont farmers were transitioning to the new bulk tanks, but the University of Vermont’s Agricultural Experiment Station was skeptical that farmers would see much benefit. In a booklet titled “Economic Effects of Bulk Milk Handling in Vermont,” agricultural economist Robert Sinclair examined the pros and cons of bulk tanks. Sinclair found that the tanks reduced some strenuous labor on the farm, mostly from farmers not having to lift milk cans, which weighed roughly 90 pounds, into coolers. He found, however, that farmers would save little or no time. The bulk tanks just required them to perform different tasks with their time.

Sinclair questioned the claim by handlers that bulk tanks led to higher-quality milk, one of their main selling points. He said that the tanks did a good job rapidly cooling the milk, an important factor in milk quality, but stated that farmers could get similar results if they used new, seamless stainless steel cans.

The biggest issue, from the farmers’ perspective, was that bulk tanks were expensive pieces of equipment. Installing a tank was a major investment, particularly for small farms. In a 1988 interview, Everett Willard, a former dairy farmer and master of the state Grange, recalled that installing a bulk tank could cost the equivalent of the net annual income for some farms. Part of that cost was often the expense of building a larger milk house to accommodate a bulk tank.

Handlers’ cost of hauling milk from bulk tanks varied widely, Sinclair noted, depending on the distance of the farm from the creamery and how many farms they could serve on the same route. Large farms on main roads were the cheapest to service. Of course, thousands of Vermont farms were neither large nor on main roads. Haulers’ policies would change that.

Handlers initially offered premiums for milk from farmers who switched to bulk tanks. Handlers then started refusing to accept milk stored in cans, so farmers who resisted buying bulk tanks had to switch to handlers willing to take their milk. Eventually, those farmers ran out of options as more handlers required bulk tanks.

Farms in remote parts of the state had no choice but to close. “I think the more modern times have put some farms out of business simply because of their location,” George said. “If they’re not convenient, some milk handlers just won’t go and pick them up.”

As small family farms closed, some sold their land to people who had recently moved to the state and to second-home owners. Others sold their land to the remaining farmers, who found they had to expand and increasingly mechanize their operations to satisfy a fluid milk market that demanded cheap milk. Farmers increased their herd size to reduce their per-gallon cost of producing milk. Larger herds forced farmers to switch from growing cash crops, such as oats and wheat, in favor of hay, corn and silage crops to feed their animals. To maximize yield, farmers turned to chemical fertilizers and hybrid seeds. To manage their expanded farm, farmers stopped tilling fields with horses and oxen and started buying tractors.

New agricultural technologies have enabled the fewer than 1,000 dairy farms that remain to produce more milk than the 10,637 that existed in 1953. But they haven’t left much room for the small family farms that once shaped Vermont society.