[W]hen Penny Patch hears about each new instance of voter suppression around the country, particularly in the South, “it just triggers the old memories.”

And there have been many.

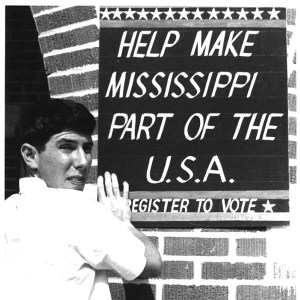

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, nearly 100 bills aimed at limiting voter access have been introduced in 31 states. In addition, officials in some states have gone to great lengths to suspend voter-registration applications, most notably in Georgia in advance of Tuesday’s election.

In 1962, Patch dropped out of Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania and spent three challenging years as a volunteer civil rights worker. In Georgia and Mississippi, the Lyndonville resident was arrested eight or nine times.

The crime? Canvassing door-to-door to register Americans who — in the current parlance — wanted to vote while black.

“The worst part of prison was that they segregated us,” Patch recalled. “As a white girl, I was jailed with white female drunks or prostitutes. My black colleagues in the movement were put in different cells. And they were beaten.”

Patch is among several Vermonters who jumped at the chance to help organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) in a massive voter registration campaign more than five decades ago. Earlier desegregation efforts had tackled schools, public transportation and lunch counters; in the push for equality, the ballot box was next on the list.

’An air of violence hung over the city’

The Constitution’s 15th Amendment of 1890 ostensibly guaranteed all adult citizens the right to vote. But 35 states (Vermont not included) enacted Jim Crow laws to deny universal suffrage.

A relatively new approach to fighting this disenfranchisement emerged in 1964. SNCC and CORE decided to recruit white youngsters to toil alongside their black counterparts for what was dubbed the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project. About 1,000 college students from other states applied, in an initiative that was geared to focus more national attention on the struggle.

One of those kids was Jake Blum. His assignment in Hattiesburg turned out to be an eye-opener for the 18-year-old who had just finished his second semester at Yale University.

“How racist really was it? Extremely,” Blum explained. “An air of violence hung over the city.”

While he was still at the requisite Ohio training session in late June, three Freedom Summer workers — James Chaney, David Goodman and Mickey Schwerner — went missing after a police traffic stop near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Their bodies weren’t discovered for two months.

Like his fellow incoming volunteers, Blum did not retreat to the safety of college life.

The Hattiesburg experience shaped him, promoting an interest in civic engagement. After moving to Vermont in the early 1970s, he’s been a Norwich town tree warden, volunteer firefighter and EMT, a natural foods advocate, and a board member of White River Junction’s Good Neighbor Health Clinic.

Blum — who more recently relocated just across the border to Hanover, New Hampshire — went door-to-door in Mississippi on behalf of SNCC to encourage voter registration. He was partnered with a white student from Stanford University in California and they relied on local people for housing.

“A black family took us in, at great risk to themselves,” Blum said. “Their own our children all had to sleep in the same bed so that we could stay there.”

Luckily, he survived the 24 hours behind bars for a trumped-up traffic violation similar to the one that had spelled death for Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner.

’I hoped people would wake up’

For Gail Falk of Plainfield, a spring 1964 SNCC presentation in Massachusetts immediately persuaded her to devote the summer to voter registration efforts rather than be a camp counselor.

Among the awkward but essential questions asked at her SNCC interview in Cambridge, where she was a Radcliffe College junior: “Are you willing to take directions from Negroes?”

Once accepted for the project, Falk learned the harsh realities of this endeavor. “They wanted to make sure we really knew what we were getting into,” she noted. “There were rules: White women must not be seen in a car with black men. Never stand in front of a window at night with the lights on.”

In Meridien by the first week of July, Falk began teaching at the Freedom School set up by CORE to offer subject matter not provided for the African-American community within the public education system. The goal was to acquaint students with publications by black writers, with a different version of history than was available in the South, with the arts, with politics and citizenship topics that stressed the importance of voting.

Ironically, Falk ended up as an impromptu French instructor because Meridien parents wanted their offspring to be introduced to the same foreign languages normally only accessible for white students.

Textbooks were in short supply, so the staff used mimeographed excerpts. “One med student with us was teaching biology,” Falk pointed out. “He caught a rat for his students to dissect.”

She took a college semester off to continue at the Freedom School. Her dedication to the Mississippi project is now juxtaposed with 2018 tales of voter suppression

“I hoped people would wake up,” Falk lamented. “It’s discouraging and demoralizing to believe the arc of history that bends toward justice may be sliding backwards.”

’Deeply disturbed’

Tamar Cole of Montpelier is “deeply disturbed” by present-day maneuvers that are thwarting the momentum of souls to the polls. At age 20 and living in New York City, she made a life-changing detour to Jackson, Mississippi.

While visiting Japan this month, Cole wrote an email about her experiences in the civil rights milieu: “My work was threefold. Door-to-door voter registration, setting up and teaching in Freedom Schools. …”

She also helped staff the Watts line, which was a system for volunteers in the field to phone the Council of Federated Organizations, the movement’s umbrella group, if they ran into trouble. “We at headquarters would then do our best to assist them, call the FBI, etc.”

After almost 12 months in Mississippi and a subsequent kayak trip, Cole landed at Goddard College in Plainfield. A long stay in Vermont was followed by another New York stint for her, before she headed back to the Green Mountain State six years ago.

Along the way, Cole noted, “I have had many careers… most significantly writer, teacher, licensed mediator, and private investigator (working primarily for civil rights and criminal justice.)”

’The Hospitality State’

Jean O’Sullivan spent one semester at Goddard, sold her guitar for $150, and rode down to Georgia on a bus. Now a Democratic state representative from Burlington, she was stationed in Columbus as a field study coordinator for three months, then switched to a role in Mississippi, “the Hospitality State.”

During the application process up north, O’Sullivan’s response when asked “What are you most afraid of [down South]?” had been “Bugs.” But in Mississippi, where she slept three to a bed at the home of local supporters, the insects were far less threatening than the racists.

One of the girls sharing that bed with her was Barbara Chaney, sister of the young black man — James Chaney — abducted and killed in June 1964 along with two white volunteers. They had been incarcerated for a theoretical traffic violation in Philadelphia, a Neshoba County town.

On a late 1965 trip in the same area, the women were pulled over by police in Carthage (about a half-hour from Philadelphia) for driving 5 miles over the speed limit, arrested and taken to jail.

“A crowd of men began gathering,” said O’Sullivan, who was told in her phone call to Freedom Summer legal aid advisers. “Do not let Barbara go out of there by herself.”

The Carthage throng apparently had been informed that she was James Chaney’s sister and therefore a tempting target for anyone with murder in mind. O’Sullivan was only allowed to post the $5,000 bail by proving she had financial resources — in the form of checks not yet cashed from a fundraiser her supportive Connecticut parents had held to benefit the cause.

“After being freed, we drove for hours on backroads with the headlights turned off,” she recounted. ”Barbara was very quiet.”

’The longer I was there, the more scared I got’

Penny Patch’s parents were also social justice allies. “They sent bail money not only for me. My family raised funds, wrote letters, and contacted members of Congress and the media.”

Her Mississippi sojourn encompassed two months in Greenwood and a year in Panola County. She left the state in August 1965. “The message from our organizations was clearly, ‘We need you to work in your own communities.’ That was painful for me at the time, but they were right,” she acknowledged.

Patch and her boyfriend, Freedom Summer volunteer Chris Williams, soon immersed themselves in the anti-war movement in California. He hailed from Shaftsbury, so Vermont beckoned the couple in 1970. A career in nursing and midwifery now behind her, among other pursuits she raises money for groups such as Black Lives Matter.

The voter suppression that’s reared its ugly head again is dredging up recollections of a bleak period in a dangerous region. “At age 18 or 19 I knew that, if riding in an integrated car, I needed to lie on the floor in the back, covered by a blanket,” Patch said. “The longer I was there, the more scared I got.”

’I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired’

Jake Blum and Jean O’Sullivan both trekked to New Jersey in solidarity with the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which was attempting to replace the official all-white state delegation at the August 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City. Their unsuccessful battle was led by civil rights pioneer Fannie Lou Hamer, born one of 20 children in a sharecropper family on a Delta cotton plantation. She delivered a heart-wrenching speech that described her routine brutalization for trying to become a voter.

A memorable Fannie Lou Hamer statement at the convention: “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

O’Sullivan left Mississippi before Christmas of 1965 due to a bout of pneumonia and exhaustion.

’The only righteous white man in Selma’

After the Democratic convention, a year passed before enactment of the August 1965 Voting Rights Act. The landmark legislation followed a legendary winter march from Selma to Montgomery that encountered a rampage by Alabama state troopers, earning it the nickname Bloody Sunday.

Most of the casualties were taken to the Good Samaritan Hospital, the only medical facility in the city open to African-Americans. The staff was largely comprised of priests and nuns from nearby St. Elizabeth’s Parish, where the activist pastor was a Vermonter.

The Rev. Maurice Ouellet, a native of St. Albans, graduated from St. Michael’s College in Colchester in 1948. His branch of Catholicism, the Edmundites, had begun serving the black community of Selma a decade earlier.

On Bloody Sunday Ouellet was just finishing a mass when, so to speak, all hell broke loose. He rushed to Good Samaritan and tended to badly injured marchers, among them SNCC coordinator John Lewis, a U.S. congressman since 1987.

According to a 2015 story in the Catholic Reporter newspaper, Martin Luther King Jr. once suggested that Ouellet was “the only righteous white man in Selma.” Could criticism from bigots and their enablers be far behind? The good works of those clerics prompted intimidation by local politicians and death threats from the Ku Klux Klan.

The Edmundite advocates in Selma also had to contend with escalating disapproval from the conservative church hierarchy, specifically a Mobile archbishop alarmed that “racial meetings” were being held in the parish.

Ordered to leave Alabama, Ouellet eventually went back to his Vermont alma mater as director of the Student Resource Center, from 1974 to 1982.

But Selma must have seemed as much a calling for him as his religious path did. It’s where he resettled in 2003, after retiring, and where he chose to be buried in 2011, at age 84.

His courageous dissent was enshrined in 1995, during Selma’s 30th anniversary commemoration of Bloody Sunday: Ouellet became the first Catholic priest to be inducted into the National Voting Rights Hall of Fame.