Editor’s note: This is the first of a series of candidate profiles that VTDigger will publish in the weeks leading up to Vermont’s 2018 primaries and general elections.

James Ehlers, a maverick environmentalist, a crusader for the marginalized, and a Democrat running for Vermont’s highest public office, says he has no interest in singing from “the party song sheet.” And few who know him would expect him to.

When Ehlers came into public view in the late 1990s and early 2000s as editor of Vermont Outdoors, a now-defunct hunting magazine, he gained a reputation as a boisterous defender of working class Vermonters — quick to lash out at what he saw as hypocrisy or injustice, regardless of where it fell on the political spectrum.

Ehlers used his magazine in the early 2000s to lambast Democrats and environmentalists because he believed that in their zeal to protect a tract of Northeast Kingdom forestland, part of a 133,000 acre swath of land purchased from Champion International, a timber company, they were going to kick camp owners off their land.

While head of Lake Champlain International, which advocates for water quality with a focus on recreational fishing, he clashed with then-Gov. Peter Shumlin, a Democrat, over Act 64 — Vermont’s own Clean Water Act — calling it a “sham.”

“I have a long track record of sticking [to] and advancing the truth, regardless of which party is putting it forward,” Ehlers said in an interview last week.

Ehlers is running as a progressive Democrat on a platform prioritizing a higher minimum wage and paid family leave programs for workers, universal health care, an environmental policy focused on pollution reduction, and a plan to increase taxes on Vermont’s most affluent residents.

“I want to make sure that the most marginalized voices in all of this … are being represented in our government policy,” he said.

But as Ehlers has campaigned around the state, he has been trailed by writings and statements from the past that revealed a candidate whose opinions contradict the progressive values he claims to be fighting for.

In commentaries, statements and social media posts — which Ehlers has published over the course of the last 20 years, in print and online — he has bashed unions, Progressives, Democrats and environmental groups.

He refers to himself now as a pro-choice candidate, but views expressed in the past indicate otherwise.

Ehlers says he is the same person now as he was then, that he has undergone no transformation, and that he has always backed policies and platforms prioritizing the needs of marginalized Vermonters.

He dismisses the divisiveness of his writings by saying that it was an adversarial technique: as an advocate he would say and write things to intentionally provoke and challenge others’ preconceived notions.

“An agitator, that was the role I filled. And for good purpose because other people weren’t asking the hard questions of allies and opponents alike, which I will do,” he said. “I think one of the most dangerous things about governance is just accepting everything at face value from allies, and never be willing to be self-critical and self-reflective.”

Ehlers has always been a critic of money’s influence in politics. Last week, he berated his opponents in the governor’s race, incumbent Republican Gov. Phil Scott and Democrat Christine Hallquist — his main competitor in the upcoming Democratic primary — for accepting corporate campaign dollars. He urged them to give the money back, which neither of them have agreed to do.

Past attacks, however, have bordered on bombast, with references that appeared racially tinged.

In a column entitled “Working White Guy Assertiveness Training,” written in June 2002 for the political website politicsvt.com, Ehlers goes on at length about how angry he is, at state institutions, state government and especially then-Democratic Gov. Howard Dean for ignoring the needs of ordinary Vermonters.

“In fact I have had it with being marginalized because I am a working white guy,” Ehlers wrote. “My ancestors were not kings nor plantation owners. Why I should have to make up for the wrongs of the privileged is beyond me.” He added that he never had “racial issues” himself. “I was around kids and adults of different ethnicity my entire life. I knew early on that we all bleed red.”

“It angers me that Howard Dean can say that people who drink Budweiser are less socially responsible, and there is no outrage from the liberals, crying of discrimination,” he wrote. “Could you imagine were he to say the same of those who drink rice wine? Yikes.”

“I am so angry I might even do something,” he wrote. “Like throw some toys into the woods. Or better yet, do something — like vote … And might even be mad enough to take the time to get all my angry white men friends to vote, too.”

In a May 2002 article, also published on politicsvt.com with the headline “Years of Hypocrisy and Lightyears of Truth,” Ehlers criticized the state’s Progressives for also being beholden to monied interests.

“The Progressive Party represents working class people so long as they have enough money to support their liberal special interests positions,” he wrote. “Be careful here, as well as they will mock and ridicule those that think differently all the while hiding under their rainbow flags.”

VTDigger located archived versions of the website via “the Wayback Machine” — a tool that allows users to access old websites — after interviewing Ehlers last week.

Asked to comment on the writings on Monday, Sarah Anders, communications director for the Ehlers campaign, said the candidate “apologizes for the hurtful comments in these 16-year-old columns.”

“Since then, he has grown in both viewpoint and approach,” Anders wrote in an email.

Ehlers may have had harsh words for the Progressive Party, but that didn’t keep him away from it. In the same year he wrote the piece denouncing the party, he volunteered for the campaign of Sen. Anthony Pollina, P/D-Washington, who was running for lieutenant governor.

Pollina, who is now a Washington County senator and chair of Vermont’s Progressive Party, likened Ehlers to Teddy Roosevelt, the Republican outdoorsman and hunter who, the longer he was in politics, hewed increasingly progressive.

Pollina said that while Ehlers was viewed early on “as a more conservative person politically,” in part because of the time he spent working with gun rights advocates and sportsmen, he appeared to undergo a political transformation in the early 2000s.

“I think that time that he spent helping out on the campaign and the time he spent afterwards being involved in the party for a bit probably helped him move in a more progressive direction,” Pollina said.

“I think sometimes people say ‘Well he’s conservative.’ And I think there’s some truth to that,” Pollina said. “I think he’s a person who’s evolved over time.”

A circuitous path to politics

Ehlers’ path to activism and political ambition in Vermont was far from straight and narrow.

He grew up in blue collar family in Oyster Bay, Long Island. Recounting a challenging childhood, he says he lived with his mother and grandmother and two younger brothers in a family that struggled financially.

Ehlers said he sought refuge in the woods and on the water. He admired the memory of his grandfather, a veteran of World War II and the Korean War, and a firefighter who died in the line of duty in 1970, when Ehlers was only 2 years old.

“It was everywhere,” Ehlers said of his grandfather’s legacy. “There was no other male figure in the house.”

Ehlers was 17 when he joined the Navy, which allowed him to attend college. The Navy paid for his four years at Villanova University; Ehlers graduated with a degree in political science.

After college, Ehlers served in the Navy’s special operations until an injury prevented him from diving. Then, he became a junior officer, overseeing hundreds of recruits.

Michael Dekshenieks, a longtime friend of Ehlers’ who served in the Navy with him, said Ehlers thrived under pressure and had respect for those he led.

“He’s thoughtful, he’s always trying to do the right thing. He’s idealistic, too, in the right way,” Dekshenieks said. “He believes in things like the environment, equality, and he does the right thing. I trust him to do the right thing.”

After four years of active service, from 1990 to 1994, Ehlers said he found himself questioning the U.S.’s military involvement abroad, which he said led to his resignation.

“You’re not supposed to think, as a junior officer, you’re just supposed to execute orders,” he said.

He found himself crashing on a friend’s couch in rural Pennsylvania, age 25, sending out stacks of resumes in the mail.

What attracted him to Vermont, he said, was a story in a ski magazine that mentioned Smuggler’s Notch had “the steepest vertical drop in the Northeast.”

“I was a bit of a thrill junkie,” he said.

Ehlers went to the ski area, applied for a job and got it — cooking, dishwashing and bartending.

He didn’t stay long. As a young man in Vermont, Ehlers said, he had many jobs and careers. He worked as a logger, a farmer, and a paraeducator for special needs students. He started a fishing and hunting guide business, and worked as a freelance writer.

On the strength of his writing for Vermont Outdoors, he was invited in the late 1990s to become the magazine’s editor.

Ehlers used the magazine as a platform to advocate for the interests of sportsmen.

Much of his personal writing for the publication focused on expressing his opposition to efforts by environmental organizations to restrict some uses of the Champion International property — a 133,000 swath of forestland in the Northeast Kingdom.

Environmentalists were considering banning logging and fishing with live bait, as well as limiting road access, in a state-owned portion of the forestland, an area known as the West Mountain lands, between 10,000 and 16,000 acres, according to an Associated Press report from 2001.

The forest tract, which featured wetlands and rich biodiversity, also happened to be home to many camps, which Vermonters had been leasing from Champion International for years.

Many who worked for environmental groups at the time declined to speak to VTDigger on the record about Ehlers’ opposition to the land deal.

But in his writings from the time, his opinions are clear.

“Apparently, even though these lands have been logged, hunted and fished for hundreds of years, there are some environmentalists and state officials that would have us believe they are suddenly endangered by the very same activities,” he wrote in an op-ed in the Burlington Free Press, in September 2001.

Ehlers suggested the proposal to conserve the land was “part of some master plan, as some in the Kingdom suggest, whereby Chittenden County types allow the Kingdom to spin into economic doom so that it can then be bought up and become a playground for the privileged.”

Ehlers is still proud of his advocacy on behalf of camp owners, regular Vermonters who he says were going to be forced off the land. Environmentalists exaggerated the “pristine” nature of the forestland, he said.

In reality, he says, it was “old logging camps where every tree had been cut down several times over the last 200 years.”

“After the money was doled out, then they wanted the camps gone,” he said. “We won.”

Ehlers said there also had been talk of developing the land, which he adamantly opposed.

“We want to keep it undeveloped because that’s where we go call moose and that’s where we deer hunt.”

Since the Champion land spat in the early 2000s, Ehlers said he has worked with the same environmental groups he once opposed, including The Nature Conservancy, to save land that’s “environmentally sensitive scientifically.”

He has been widely recognized for his work as executive director for more than 16 years of Lake Champlain International, an advocacy group that draws attention to, and raises funds for, Lake Champlain water quality, by among other things organizing fishing “derbies” — drawing thousands of anglers to the state.

For his leadership at Lake Champlain International and the group’s efforts on behalf of the lake, Ehlers was recognized in 2012 by the Environmental Protection Agency. In a news release from that year, the EPA praised Lake Champlain International for its efforts to help homeowners install stormwater runoff prevention features, and for the millions in federal funds it had acquired for Lake Champlain conservation projects.

The labor candidate

Ehlers has been a relentless critic of the incumbent governor, Phil Scott, targeting in particular his treatment of workers and his stances on labor issues.

“In his short time as governor he has taken every chance to target public sector unions,” Ehlers said at a news conference last month, noting Scott’s fraught negotiations with the state employees union and efforts to cut teacher health care costs.

In recent weeks, Ehlers turned out on the picket line for two days of strikes with UVM Medical Center nurses in their fight for better pay and staffing conditions.

Two major unions, the Vermont Building & Construction Trades Council and the Vermont AFL-CIO — which represents a number of smaller unions — have formally endorsed him.

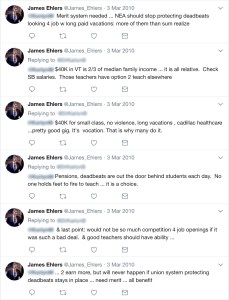

But in the past, Ehlers has been somewhat less enthusiastic about unions. In 2010, he tweeted that the NEA, the union which represents 12,000 teachers and other educators in Vermont, “should stop protecting deadbeats.”

“Good teachers should have ability 2 earn more, but will never happen if union system protecting deadbeats stays in place,” Ehlers wrote in another tweet.

Ehlers says the tweets do not indicate that he ever held anti-union views.

“I didn’t call all NEA members deadbeats, I was engaged in an adversarial paradigm which is taught in law school debate, where you confront people on their own views to get to the truth,” he said.

“It does not change my support for unions,” he said. “I’m here because of my grandfather’s union benefits.”

Since the tweets came to light, the unions backing Ehlers haven’t wavered in their support for the candidate, but he has come under fire from the Vermont NEA.

“Those tweets are some of the ugliest anti-union rhetoric that we see. Those tweets are offensive to our 13,000 members who are every day in our schools for our kids doing work,” Darren Allen, a spokesperson for the union, said in an interview last week.

“There’s a difference between provoking conversation and then the sentiments expressed in those tweets,” he added.

Pollina was also critical of Ehlers’ tactics, and his claim that they’re for the purpose of provoking thought, and debate about contested issues.

“I think it’s reasonable for people to be turned off when they see those kinds of statements,” Pollina said of Ehlers’ social media writings, noting that he neither condones nor agrees with everything the candidate has said or done.

“I think there’s better ways to agitate if that’s your purpose,” he added.

In last week’s interview, Ehlers readily admitted he’s no “cookie cutter, just-add-water politician.” Over the years, he said he has had many labels attached to him, and found himself painted in colors across the political spectrum.

He acknowledged in the interview that the explanations he has offered for some of his more provocative past statements — that he has sought only to play devil’s advocate and challenge others’ views — could be regarded as suspect: an attempt to explain away views he may once have held.

“As someone who’s running for office now, yeah I can see it that way,” Ehlers said.

“But not as someone who had no aspirations, who was on the tip of the spear so to speak, on forcing people to think. That’s the role that I filled,” he said.

“And that also forced me to think.”