Editor’s note: Mark Bushnell is a Vermont journalist and historian. He is the author of “Hidden History of Vermont” and “It Happened in Vermont.”

[A]s pleas for reconciliation go, this was an odd one. In many ways, it was not a plea at all. The letter writer alternates between cajoling and accusing, begging and threatening. It’s as if he doesn’t know whether he is writing to a friend or an enemy, which is odd, since the writer and the recipient were brothers.

Usually a family spat wouldn’t merit notice. Evidence of this one, however, is kept under lock and key at the Vermont Historical Society library in Barre. The two-page letter, written on thick parchment that is starting to brown after two centuries of storage, offers us a snapshot of the tempestuous relationship between two members of Vermont’s most celebrated family.

The letter writer was Levi Allen, perhaps the most inscrutable member of the famously inscrutable family. The recipient was Ira Allen, the Vermont patriot and the de facto family leader, his eldest brother, Ethan, having died four years earlier.

Levi, writing in 1793, probably from Saratoga, New York, wanted to get into the good graces of his more influential brother, who was also his sometimes business rival. Strangely, Levi starts the letter with a bit of a barb, commenting that Ira had changed, and apparently not for the better. He laments that, having just returned from England, he can “find nothing of Ira Allen remaining.” Then, in the next paragraph, he turns sentimental, referring to a family they both know that includes six brothers, just like the Allens, and that manages to carry “on Business in a Brotherly and advantagious (sic) manner …”

Levi wistfully hopes that his kin can work together. But sadly, he writes, “after insatiable death hath devoured four, the remaining two (Allen brothers) have become Strangers, and more than Strangers.”

Levi suggests that if the two can’t exactly be friends, at least maybe they could be business partners. Perhaps to show his value as a partner and to sweeten the offer, Levi casually mentions that he could help Ira secure 100,000 acres – presumably in Georgia or Florida, where Levi had been speculating.

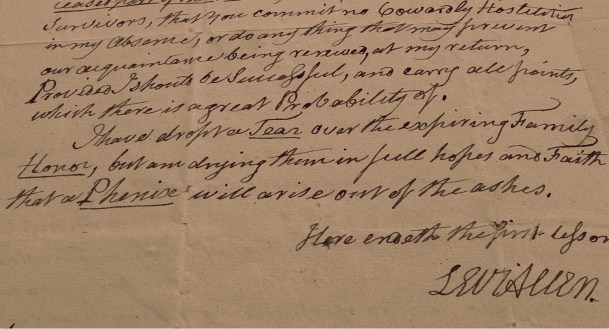

Having appealed to Ira’s hunger for a good deal, Levi tries to play on his guilt or at least his sense of duty. But before the sentence is through, he makes clear that he doesn’t trust Ira: “I ask you, I desire you, in the name of the deceased part of the Family, and for the Honor of the Survivors, that you commit no Cowardly Hostilities in my Absence, or do any thing that may prevent our acquaintance being renewed, at my return …”

Levi is leery of turning his back on Ira, and with good reason. Both were land speculators and, in a small place like Vermont, that made them competitors. Besides, they had more than their share of history, and Levi had every reason to hold a grudge.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Fourteen years earlier, Ira and Ethan had tried to use the power of the law to confiscate all of Levi’s property in Vermont. At the time, the state was in turmoil because of the American Revolution. With a large British Army encamped just to the north in Quebec, Vermont needed to defend itself, but it was too poor to fund a militia.

That’s when Ira, then secretary of the Council of Safety that ran Vermont before its new constitution took effect, hit upon the idea of seizing and selling the property of the enemies of America. Among them, of course, were Loyalists or Tories – people who sided with the British.

Ethan used Ira’s confiscation plan to make an example of Levi. Ethan filed his complaint against Levi, alleging that he was “of Torey (sic) principles.”

“Levi,” he wrote, “has been detected in endeavouring to supply the enemy on Long Island, and in attempting to circulate counterfeit currency, and is guilty of holding treasonable correspondence with the enemy, under cover of doing favours to me …”

Several years earlier, Levi had in fact been doing Ethan “favours.” And Ethan had definitely been in need of them: He was being held prisoner by the British on Long Island and Levi was working to gain his release. Ethan no doubt appreciated the help; he just didn’t like that his brother was also trading with the British.

Levi’s allegiances shifted during the Revolution. He had started the war loyal to the rebellion. Indeed, he had served as Ethan’s courier after the fall of Fort Ticonderoga at the start of the Revolution. And after Ethan’s capture during an ill-conceived attack on Montreal, Levi worked hard to secure his brother’s release. He did, however, find time to do a little business along the way. The most profitable trading arrangements he found were with the British. Levi was at heart the ultimate free trader, an early devotee to Adam Smith’s tome on the subject, “The Wealth of Nations.” Why let something trifling like a little revolution ruin business?

Revolutionary leaders had seen things differently and had placed Levi in jail for six months for trading with the British. That’s where he sat when Vermont’s Court of Confiscation ordered his property seized in January 1779. Levi received word of the seizure in the pages of the Connecticut Courant. He fired back an angry letter, which was also printed in the paper.

“To this base and inhuman attack and procedure,” he wrote, “I ask a suspension of the public opinion, until the dark, flagitious design might be developed, and my character vindicated.” The charge, he noted, had been brought by his brother, “if he merits that title.” Levi claimed that Ethan was being vindictive because Levi had refused to let Ethan cheat him in a land deal.

After his land was seized and he was release, Levi sided with the British in earnest, moving to eastern Florida and working as a supplier to the British Army. Some believe he was also a British spy.

It is easy to label Levi a traitor, but he lived in confusing times and he was hardly alone in feeling mixed allegiances. The population of the American colonies at the outset of the war was between 2 million and 3 million. Of those, as many as 250,000 fled the country as Loyalists. Historians generally believe that strong supporters of the revolt never numbered more than half the population. Many people felt deeply ambivalent about the Revolution.

Levi supported each side at different points. But his support was never steadfast. Mostly he just wanted the fighting to be over. It was bad for business.

As the war began to wind down in the mid-1780s, the British cut off ties with southern Loyalists, selling Florida to the Spanish. Cast off by the British, Levi returned to Vermont, where he promptly challenged Ethan to a duel. He was still angry about the land confiscation business. Cooler heads prevailed and the duel was called off. Eventually, Levi was welcomed back into the family. The Allens were nothing if not forgiving.

Still, Levi never seemed to find his place. He continued to live on the boundary between two worlds. Even before the war was officially over, he settled in St. Johns, Quebec, where he served as a conduit for goods traded between Vermont and British-controlled Canada. He participated in Ethan and Ira’s on-again, off-again negotiations with Canadian officials to make Vermont a British province. He argued strenuously against Vermont joining the United States. He asserted the shared interests of America and Britain in free trade.

If some Americans considered him a traitor, the British didn’t like him much better. Quebec authorities jailed him for two months in 1797 because they thought he and Ira were trying to depose the British rulers of Canada.

His relations with family members remained tumultuous, especially with Ira, the longest-lived of the Allen boys. For the rest of their lives, they were alternately partners and rivals in a series of failed business ventures. As Levi’s odd letter from 1793 shows, they could never quite trust each other.

If Levi and Ira had their differences, they sadly shared a common end.

Levi’s schemes came to a close in 1801 when he died while imprisoned in a Burlington debtors prison. He was buried in a now unmarked grave on the prison’s grounds. Ira met a similar fate 13 years later. Having fled his Vermont creditors and settled in Philadelphia, he died there penniless, his body interred in a pauper’s cemetery, in an unmarked grave.