(“Then Again” is Mark Bushnell’s column about Vermont history.)

[J]ohn Wesley Powell and his men completed their seemingly impossible adventure on Aug. 30, 1869. They emerged from running the raging Colorado River down the length of the Grand Canyon. Many people had viewed the expedition, which ran through the last uncharted place in the United States, as suicidal.

Indeed, the men had thrice been declared dead in newspaper stories. They may have realized that when they returned to civilization they would be treated as heroes. But all Powell wanted to know was: Where were the Vermont brothers and a third man who had left the expedition two days earlier?

It would be nearly three weeks before Powell learned of their fate. What he learned would haunt him and the legacy of the expedition.

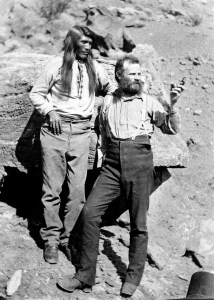

Oramel and Seneca Howland had been among the last men to sign up with Powell for the expedition. Powell, a geology professor and former Union Army officer who had lost an arm in the Civil War, had recruited a team of rugged scholars from back east and some even more rugged Western mountain men. They worked as volunteers, but some brought along beaver traps and gold–sifting pans, hoping to get rich along the way.

Powell met Oramel through a friend at the Rocky Mountain News, where Oramel had been a printer and vice president of a Denver typographers’ union.

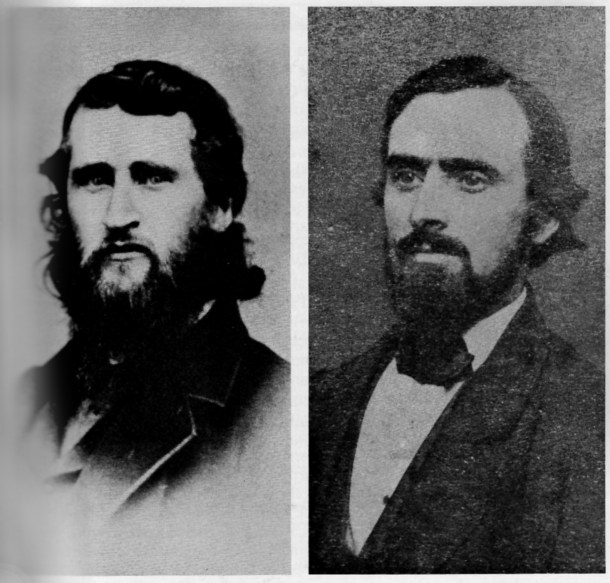

At age 35, Oramel was several months older than Powell, making him the oldest member of the expedition. With a long beard and thinning hair, which blew wildly in the wind, Oramel looked older still. He was also the most literate of the volunteers and interested in science. His intelligence and what Powell called his “faithful, genial nature” earned Powell’s trust. Oramel got the important jobs of piloting one of the four boats, making the expedition’s maps and taking field notes.

Seneca presumably signed up at his older brother’s urging, but he brought along his own skills. He was military trained and battle hardened. Seneca, 26, had served in the Army during the Civil War, enlisting in the Vermont 16th Regiment and helping repulse Pickett’s Charge on the final day at Gettysburg. After the war, he joined his brother, who had been in Denver since at least 1860.

The boys, who were half brothers, sharing a father, had apparently decided their prospects for wealth, and perhaps also adventure, were better out west. They had grown up in Pomfret, where their father, Nathan, was a successful farmer. But following custom, it was a younger brother who was helping Nathan tend the family’s 60 acres and 500-tree maple sugaring operation. The Howland brothers chose the unknowns of the West over making their way in Vermont, where career paths into farming or some trade were well worn.

Just two weeks into their trip, the Howlands nearly died. Piloting a boat called the No-Name through a canyon in the northwest corner of what is now Colorado, Oramel apparently missed a signal from Powell to pull ashore above a rough set of rapids. Or perhaps Powell never made the signal. The cause of the calamity about to unfold has been debated ever since. For his part, Oramel said they could have pulled the boat safely ashore if it hadn’t already been half full of water from the rapids they had just run.

While the men from the other three boats looked on, Oramel, Seneca and a third man, Frank Goodman, paddled mightily to avoid the rapids. Powell saw the boat pause for a moment before plunging into the whitewater. The boat struck a rock, pitching the men overboard, but it hung there, stuck, long enough for them to pull themselves back in. Though full of water, the wooden boat floated, thanks to airtight compartments.

The boat then headed into a second set of rapids, 200 yards down river. Striking a rock broadside, the No-Name split in two and the water swept the men under.

Powell and the others rushed to help. As they rounded a bend in the river, they saw Goodman desperately grasping a rock and Oramel pulling himself onto a small island in the midst of the rapids. Oramel found a pole and held it out for Goodman, who let go of the rock and grabbed hold of it. As Oramel hauled Goodman in, Seneca pulled himself ashore farther down the island.

Powell and the others managed to pluck the three off their mid-river perch, but it was too late for the No-Name. The boat was a total loss. With it went a third of the group’s rations and half of their mess kit. Goodman lost all his possessions except the clothes he was wearing and would soon quit the expedition.

The men salvaged a blue keg Howland had stowed on board. Howland mentioned the keg’s recovery in one of two dispatches he had written for the Rocky Mountain News, but he didn’t mention its contents. It held whiskey, which Powell let the men drink to settle their nerves. Despite saving the whiskey, the men took to calling these rapids Disaster Falls.

Disasters and near-disasters continued to haunt the men. One week later, they lost a second boat in some rapids, but soon found it only lightly damaged in an eddy downriver. Then, one day later, one of the men, Billy Hawkins, built a cook fire too close to some dead willows. The trees burst into flames. The only escape route was the river. The men jumped into their boats, while Hawkins grabbed kettles, bake ovens, plates and utensils and plunged into the river. When he surfaced, he had lost the plates and utensils.

“Our trip thus far has been pretty severe: still very exciting,” Oramel wrote in one of his dispatches. Despite the dangers, the rush of the water inspired the men. “As soon as the surface of the river looks smooth all is listlessness or grumbling at the sluggish current… But just let white foam show itself ahead and everything is as jolly and full of life as an Irish ‘wake.’ ”

By mid-August, they reached the Grand Canyon, but had only 10 days food left. The game that had earlier been so plentiful was gone and they could find no fish in the muddy waters of the Colorado.

Even the normally sanguine Powell worried. He wrote in his journal: “We are three quarters of a mile in the depths of the earth, and the great river shrinks into insignificance, as it dashes its angry waves against the walls and cliffs, that rise to the world above; they are but puny ripples, and we but pygmies, running up and down the sands, or lost among the boulders.”

Oramel was equally distressed. In recent weeks, his boat had swamped twice, costing the notes and maps he had been making, and robbing the expedition of much of its scientific value. Perhaps his bad luck made him feel the expedition was doomed. When they reached a seemingly impassable set of rapids on Aug. 27, he had had enough.

One of the men, George Bradley, described that day, their 96th on the water, as the expedition’s darkest. In his journal, he described the rapids: “The water dashes against the left bank and then is thrown back against the right. The billows are huge and I fear our boats could not ride them if we could keep them of the rocks. The spectacle is appalling to us.”

That night, Oramel took a walk with Powell. Once out of earshot of the others, Oramel told Powell they should give up here. To try the rapids was folly. If Powell wouldn’t stop, then Oramel said that he, Seneca and a third man, Bill Dunn, would hike out on their own. Oramel returned to the camp to sleep while Powell weighed his options.

Powell wrote later that he brooded all night and almost agreed to quit. But he decided they had gone too far to give up. He woke the men to see if they would push on. All except the Howlands and Dunn agreed to continue. By this point in the trip, Seneca had become a favorite of the others for his soft-spoken, good nature and he said he wanted to stay. But in the end, he chose his loyalty to his brother over his new friends.

The Howlands and Dunn declined an offer to take their share of the rations. They would use their rifles and shotgun to kill what they needed once they reached the world above.

Each group took a complete copy of the mission’s records, since neither group knew which was more likely to survive. Then the departing men helped the others shift the remaining gear into the two soundest boats.

The moment to part had come. All the men shook hands. Some cried. “They left us with good feelings,” Bradley wrote in his journal, “though we deeply regret their loss for they are (as) fine fellows as I ever had the good fortune to meet.”

Then the Howlands and Dunn watched the boats shoot through the rapids. This stretch, now known as Separation Rapid, proved less fearsome than it had appeared. The boats slipped through safely and around a bend in the river. The men in the boats fired off guns, hoping to convince Oramel, Seneca and Dunn to take the boat they had abandoned upriver. But they never came. In fact, they were never seen again.

Upon leaving the river, Powell and the survivors heard rumors the men had been killed by local Shivwit Indians. Powell returned to the river the following year to gather some of the data that had been lost during the first expedition. During this trip, he met with Shivwits to learn if the rumor was true. Powell’s Mormon interpreter told him that the Shivwits admitted killing the men after mistaking them for prospectors who had raped and killed a Shivwit woman.

Powell seems to have accepted the explanation, but more recently some historians have suggested the interpreter might have been lying. The Howlands and Dunn might have stumbled upon some of the Mormons who 12 years earlier had massacred 120 members of an Arkansas wagon train headed to California. The three men might have been mistaken for federal agents who were still seeking some of the killers.

However the men died, they have largely been forgotten. When a memorial commemorating the expedition was built a century ago, in 1918, on the Grand Canyon’s South Rim, the names of the Howlands and Dunn were omitted. But Powell, who had died nearly 20 years earlier, paid his own tribute to the men, naming Howlands Butte in the Grand Canyon after them.