As metastasizing cancer spread to various parts of his body, Roger Brown lay sleepless in a prison cell. Over-the-counter medications like ibuprofen and Imodium were no match for his searing pain.

In the weeks leading up to his Oct. 15 death, diaries kept by Brown and his cellmate show he was repeatedly rebuffed in his requests for treatment by medical staff at Pennsylvania’s State Correctional Institution-Camp Hill, where Vermont has housed about 270 inmates under contract with that state since early summer.

“We were continually refused medical attention,” Brown’s cellmate, Clifton Matthews, wrote in a diary entry after Brown died. He was “told repeatedly it was all in his head, even at the point where he could no longer stand or sit up.”

Matthews took over diary-writing duties from Brown about two weeks before Brown died, explaining in his first journal entry, dated Oct. 1, that “Roger could no longer concentrate to write, nor could he sit up for any length of time.”

The diaries reflect no official acknowledgment of Brown’s metastasizing cancer until that cause of death was cited on his death certificate.

Kelly Green, a lawyer with the state of Vermont’s prisoner’s rights office, called the Brown case “egregious,” while Barry Kade, a private lawyer and longtime inmate advocate from Montgomery, said the minimal treatment for advanced cancer was tantamount to torture.

“Having read Roger Brown’s journal from his last days I think it is obvious that he was essentially tortured by the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections and by inference the Vermont Department of Corrections,” Kade wrote in a text to VTDigger.

Mike Touchette, deputy commissioner of the Vermont DOC, said in an interview Thursday that Brown’s case was still under administrative and clinical review by authorities in Pennsylvania and Vermont, and that he could not comment on the particulars.

Amy Worden, press secretary for the Pennsylvania DOC, said Brown’s “Vermont DOC medical record was delivered to SCI Camp Hill along with him on June 12, 2017. At the time of reception this inmate received a complete medical evaluation and was provided any necessary treatment in accordance with DOC policy.”

Camp Hill, just west of the capital of Harrisburg in south-central Pennsylvania, is one of 25 facilities in that state’s prison system. Camp Hill, with 3,400 inmates, is larger than Vermont’s entire corrections system.

In a separate email, Worden wrote, “We have developed a very good health system which includes a designated chronic and long-term care facility, SCI Laurel Highlands, that provides in-house chemotherapy and dialysis. We provide general care of geriatric inmates and care for those with chronic conditions throughout the system. Care of inmates is constantly evaluated by trained medical professionals and quality of care is very important to us. We deliver health care services in line with community standards.”

According to the diaries, and to letters written by Matthews and another inmate, Shaun Bryer, of Morrisville, the care Brown received was nothing like what Worden described.

“Vermont inmate Roger Brown’s recent death is on the hands of every SCI-Camp Hill employee who watched as he deteriorated rapidly over a three-week period of time and did nothing about it, Bryer wrote in a letter to the editor published last week in the Brattleboro Reformer.

“He received no significant medical treatment, was returned to J-Block even after the head of medical told a Vermont Department of Corrections’ employee they would keep him for the weekend for observation,” Bryer wrote. “Brown had to be taken care of full-time by his cellmate after he could no longer stand and was only moved to medical after a concerned officer had him wheeled there by his roommate the night he died.”

Brown’s diary is a daily log that began on July 19 in a somewhat routine tone: “Breakfast, meds, lunch, Supper, meds, bed.” It first mentions lung pain in entries beginning in early August, and grows in a crescendo of agony of back spasms and difficulty breathing by late September and a last entry Sept. 28: “Breakfast, not much sleep last night, getting sick of this pain.”

Matthews then picked it up and wrote of a trip to the prison medical office on Oct. 2. “I had the sergeant declare a medical emergency because Roger was in so much pain,” Matthews wrote. “I wheeled him up to medical. We were refused. The short nurse on duty told Roger, ‘Chronic pain is not a medical emergency’” adding that “‘It’s all in his head.’ … She went out of her way to be rude to him every time he came up.”

That Oct. 2 entry followed one on Sept. 27 in which Brown wrote that a physician assistant had told him an X-ray had shown a mass on his lung. Throughout this period, pain would spike in various parts of Brown’s body. At one point his hip hurt so badly he thought it was broken.

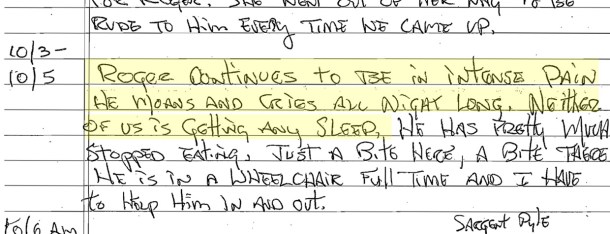

On Oct. 5, 10 days before Brown’s death, Matthews wrote: “Roger continues to be in intense pain. He moans and cries all night long. Neither of us is getting any sleep.”

Green, of the Vermont prisoners’ rights office, said she does not have medical training, but that it should have been obvious even to a lay person that Brown was suffering from metastasizing lung cancer.

“A, he had a 40-year history of smoking; B, he had a mass on his lung; C, he self-reports in his diary of bone pain; and D, there’s the fact that he died.”

Green said “it’s criminal” that he wasn’t treated aggressively for cancer and then with palliative care as he approached death.

“It’s a clear violation of his civil rights,” Green said. “No Vermonter should stand for that.”

Both Green and Defender General Matthew Valerio said aging, illness and death are becoming more common in prisons as inmates age. More inmates are dying in prison because of longer prison sentences that began to be imposed in the 1990s for sex crimes and homicides, they said.

Aging inmates dying behind bars is “a significantly growing area. It’s going to happen more and more,” Valerio said.

Prison medical care is not covered by Medicaid, he said, meaning states pick up the entire cost.

Another inmate at Camp Hill, 59-year-old Timothy Adams, was brought back to Vermont for palliative and hospice care before dying at the Southern State Correctional Facility in Springfield on Nov. 3, Touchette said last week. Valerio said he had cancer as well.

Brown had lived in with Windham County hamlet of Brookline and was 68 when he died. He had worked as a car mechanic, a machinist and as a “jack of all trades,” his widow said. He was serving a six- to 15-year sentence for three counts of lewd and lascivious conduct with a child between 9 and 11 years old.

His widow, Joanne Brown, said the conviction was based on “bullshit charges. … The man paid for something he didn’t do with his life. That’s how I look at it. … Can you imagine dying of fourth-stage metastatic lung cancer and you’re not on anything but ibuprofen? I can’t imagine the shape he had to be in. It just breaks my heart.”

During an interview, she read from a letter she had received from her husband’s cellmate, Matthews.

“They really pretty much killed him,” she read. “They refused him medical attention for weeks. Do not let them tell you different. I will be happy to testify to that. … Nail the bastards for Roger. I’ll help in any way I can.”

Kade, the Montgomery lawyer, said he had been involved in inmate rights issues for more than 20 years, including in the response to seven inmate deaths in the early part of the last decade. Those cases led then-Gov. Jim Douglas to order an independent review of medical and mental health treatment offered to prisoners, Kade said.

“I think it is appropriate for this governor, Gov. (Phil) Scott, to conduct a similar investigation and let the chips fall where they may,” he said.